Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

A Revolution through ordinary citizens’ eyes

The American Philosophical Society presents Philadelphia, The Revolutionary City

Philadelphia was in turmoil: taxes were rising, restrictions on day-to-day life increasing, and the head of government was behaving like a tyrant. People were angry. Revolution was in the air. The year was 1775.

It’s well known what the Founding Fathers were doing in the run-up to independence, but what about everyone else? What were the merchants, farmers, servants, and all of the women thinking and doing? Philadelphia, The Revolutionary City, at Old City’s American Philosophical Society (APS), opens a window into what was happening below history’s surface.

An online history portal becomes a physical exhibition

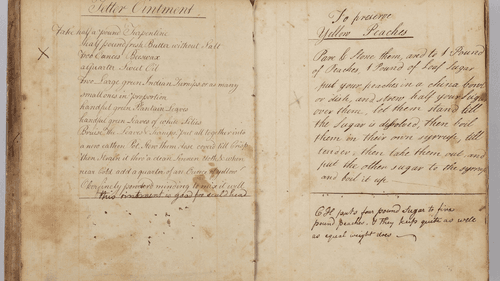

Eighteenth-century Philadelphia is made tangible in original documents, images, and possessions. We meet Catharine Haines through her household notebook (1776, APS), open to a formula for “tetter ointment” for the skin and, on the facing page, her method of preserving yellow peaches. Long before electronic and virtual media, people gained information by reading newspapers and broadsides (notices posted in public places). They wrote letters, visited coffeehouses to hear the latest, and talked with one another.

Curated by Caroline O’Connell of APS, the exhibit brings together a wealth of materials from APS, the Historical Society of Pennsylvania (HSP), Library Company of Philadelphia (LCP), the Museum of the American Revolution (MOAR), and University of Pennsylvania’s Kislak and McNeil Centers for Early American Studies, in addition to other institutions and private collections.

The exhibition was inspired by an eponymous portal launched in 2023 by the lead institutions to provide the public with virtual access to period materials in a single searchable location. The portal, therevolutionarycity.org, will be available long after the physical exhibition ends, and it’s still growing: as of December 2024, 46,000 manuscript pages had been digitized.

Workshop of the pre-Revolutionary world

Besides perusing Philadelphians’ correspondence and reading their diaries, visitors can see things they made, owned, and used. Among the items in APS’s second-floor gallery are furniture, art, currency, lottery tickets, tableware, a cloth wallet, and even silk shoes worn by 20-year-old Hannah Marshall at her wedding to Casper Wister Haines (1785, Wyck Historic House and Garden).

As the seat of colonial power and headquarters of the Continental Congress, Philadelphia had a thriving economy. Legions of skilled craftsmen advertised on beautifully engraved trade cards. Cabinetmaker Benjamin Randolph’s card (1769, LCP) directs customers to find him at “the Golden Eagle on Chestnut Street.” Edward Pole (c. 1770, HSP) listed himself as a “fishing-tackle-maker” and included a scene of an angler with a line in the water.

A walnut and mahogany grandmother clock by Edward Duffield (c. 1750, APS) is thought to have stood in the library of his close friend Benjamin Franklin. Franklin could not have checked the time often, though, because he spent these years abroad, representing first the colonies in England from 1757 to 1775, and then the emerging nation in France from 1776 to 1785.

Patriots, loyalists, and pacifists

Questions of whether to separate from England and which side to support during the war thread through the artifacts, as do calls for peace. Some people vacillated, transferring allegiance with the state of the war—Philadelphia was occupied by the British for nine months in 1777 and 1778.

As pacifists, Quakers were particularly vulnerable, as entries in diaries by Sarah Logan Fisher and Elizabeth Sandwith Drinker (1777, HSP) indicate. Both women witnessed their husbands’ arrest for refusing military service.

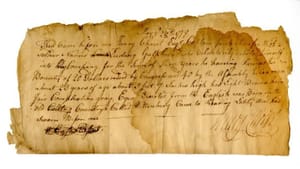

Enlistment documents on view range from a neat letterpress pledge required of all Continental Army officers (1778, HSP) to yellowed, torn receipts written in iron gall ink (1778, APS). Signed by Ludwig Guthbroad and Jacob Detrick, the receipts committed them to Pennsylvania’s 6th Regiment in Berks County, and earned each a 60-dollar bonus.

Handwriting: the new hieroglyphics

As a center of commerce and culture, Philadelphia was a crossroad for all sorts of people, illustrated by a 1775 broadside (LCP) in German stating the Mennonite community’s pacifism. Germans, who were numerous in Pennsylvania, are also represented by colorful fraktur documents (1769, 1788) from the Reading Public Museum. Frakturs were produced to mark marriages, baptisms, and other important genealogical events.

No matter how humble the document, the handwriting is beautifully formed and, in Charles Willson Peale’s military field diary (1776, HSP), incredibly tiny. It’s open to his impressions for July 2, 1776, the day Congress approved the Declaration of Independence.

But excellent script can be difficult to read, especially for eyes not used to cursive. To help, the exhibit gives voice to a few key artifacts at listening stations. Visitors can both listen to and read remarks made in 1776 by Captain White Eyes, a Lenape leader, to Congress.

Another station narrates an indenture agreement (1781, HSP) for John Francis, a free Black man. Francis placed his mark on the document, promising to work for Richard Walker of Bucks County for the sum of 45 dollars, the price of freedom for his wife Jane.

Preparing the portal

Transcribing portal documents into printed text began in October 2023. Educators consulting with the portal development team, led by Bayard L. Miller of APS, emphasized the importance of making digital materials accessible to users of all ages and abilities, and ease of reading is paramount.

Entries on the portal blog explain the project’s scope. “The Revolutionary City seeks to digitize all manuscript material to, from, or about Philadelphia during the American Revolutionary War (1774-1783),” wrote David Ragnar Nelson of APS.

Volunteer transcribers learn “tips and tricks” and work in groups, explained APS’s Alexandra Rospond: “Our transcribers were asked to write out the letter exactly how it is written. This includes keeping misspelled words, punctuation (or lack of punctuation), and even randomly capitalized letters.” Brackets indicate words that cannot be deciphered.

Machine learning is also used. While typical optical scanning recognizes print, it puzzles over cursive, Nelson explained. Deep machine learning, when successful, speeds transcription, making a first pass that’s followed by human verification. “The computer cannot ‘see’ or ‘read’ letters in the same way that a human being can,” Nelson wrote, “but associates the contours of visual material on the page with the probability of being a certain letter.”

Is past prologue?

The Revolutionary City anticipates 2026, the 250th anniversary of American independence, but its themes could not be more current. Daily, principles enunciated in the Declaration of Independence and Constitution are being challenged and twisted to serve modern tyrannical agendas. Ideals enshrined in the American legal system are being relitigated. And progress made over decades toward a more perfect union is being sabotaged. As in 1775, what happens next depends on the people, all of us. Democracy requires vigilant citizens, always.

What, When, Where

Philadelphia, The Revolutionary City. Through December 28, 2025, at the American Philosophical Society, 104 S 5th Street, Philadelphia. (215) 440-3400 or amphilsoc.org.

Accessibility

APS Museum is located on the building’s second floor, and is reached by a flight of stairs inside the entrance. A wheelchair lift and elevator are available for visitors who require them; staff are happy to assist. The nearest public restrooms are located two blocks away at the Independence Visitor Center. Please direct accessibility questions to APS Museum Education or (215) 440-3440.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.