Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Thrilling metatheatrics

PSF presents Shakespeare’s Hamlet and Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead in rep

We often say plays are in conversation with each other, but rarely is the sentiment so thrillingly realized as when the same cast performs them, on the same stage. Pennsylvania Shakespeare Festival ignites a repertory staging of Hamlet and Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead—two exemplary scripts which, when held together, generate friction and spark.

A derelict world

Let’s start with Hamlet (the older of the two plays by 366 years, give or take). Directed by Lindsay Smiling in sharp, unfussy fashion, this Hamlet cuts right to the engine of Shakespeare’s play and animates the Danish prince’s equivocations with propulsion and verve. If it doesn’t quite sustain its energy all the way through, it consistently reveals itself in dynamic bursts of staging, especially with its decayed setting and particularly libidinous Hamlet.

When Hamlet says that something is rotten in the state of Denmark, you can see it firsthand. The castle is cracked, the scaffolding peels. The lighting comes from a striking blend of chandeliers dangling askew and more modern bars of neon light (scenic and lighting design by Brian Sidney Bembridge). It is as if the state itself is riddled with disease, crumbling beneath the weight of a time out of joint.

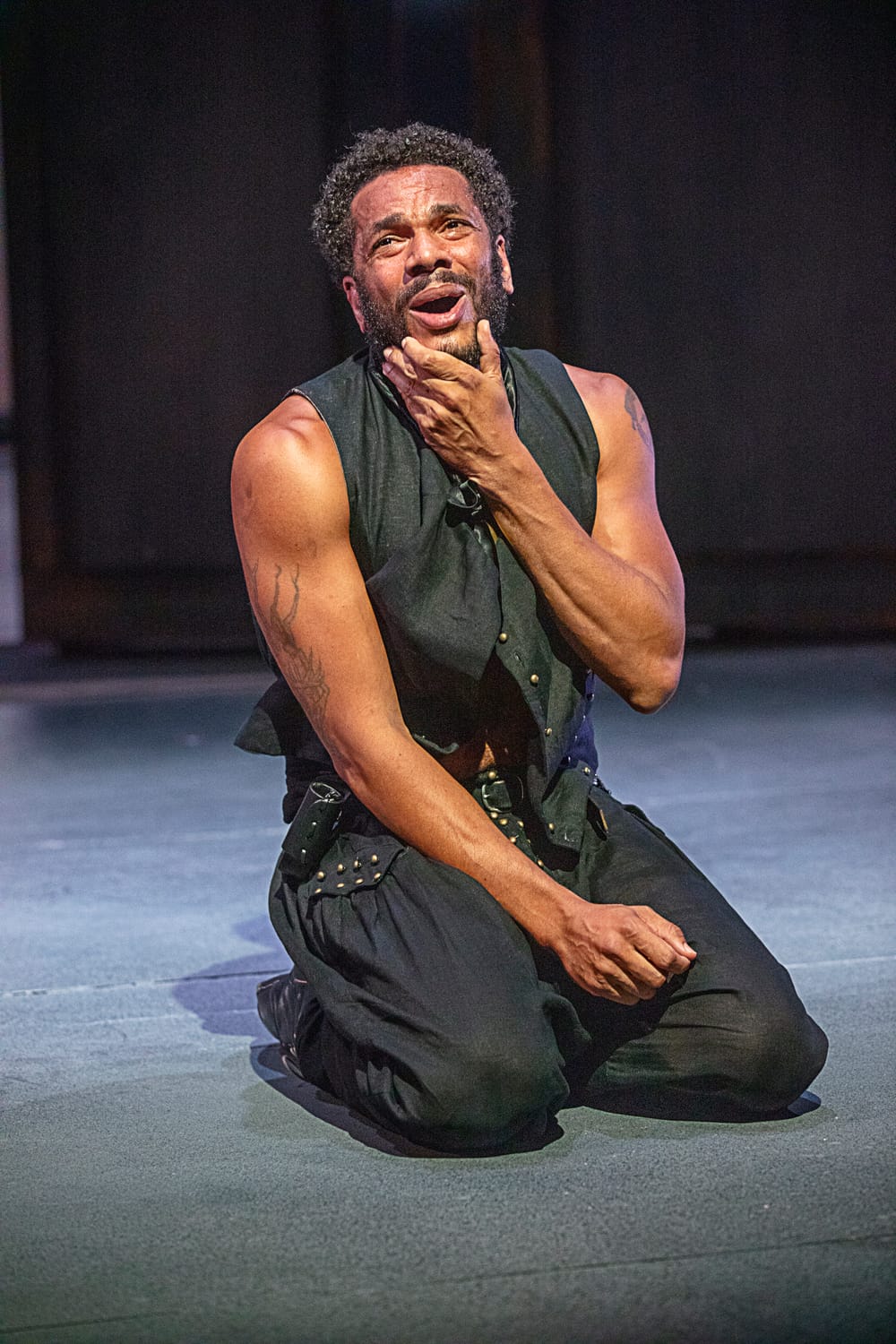

Such a derelict world provides an excellent backdrop for an intensely horny Hamlet (Biko Eisen-Martin), who practically writhes about the stage with sexual frustration. Eisen-Martin’s Hamlet humps the ground before Polonius’s feet, kisses his uncle’s cheeks with something more than filial piety. His fitful machinations are thus channeled as the sometimes stalling, sometimes rash, impulses of a sexually frustrated young man—constant in their erraticism, often indecipherable even to himself.

Denmark bleeding

Much of the supporting cast excellently buoys Hamlet’s insanity. Eric Hissom’s Polonius, a standout, is played to maximum comedic effect, puttering about in a continual state of befuddlement. The dead king’s ghost (Damien J. Wallace) similarly counterbalances his randy son, treading the stage with an otherworldly sense of menace. Others are less successful in hitting their marks. Pepin’s Ophelia is a breathy creation, too light to land with any real weight, while King Claudius (Akeem Davis) and Queen Gertrude (Grace Gonglewski), though suitably regal, never quite conjure the chemistry necessary to rankle their sometimes son.

This production also struggles to sustain its energy in the latter half. After Polonius’s death, the play must necessarily settle into a more pensive register, but in doing so, it leaves some of its passion behind, less certain of its animating thrust. Even so, the play eventually rediscovers itself with the return of Laertes (David Pica, a fervent match for Eisen-Martin’s Hamlet), providing a shot in the arm. In the final scene, with the tragedy at its most inevitable and messiest, Pica and Eisen-Martin achieve a delicately somber resolution, grieving for this world of theirs. It feels that Denmark itself is bleeding, a body politic so irreversibly poisoned that its innards must finally spill out.

A healthy dose of existentialism

The Lion King 1½ to Hamlet’s The Lion King, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead revisits the story of Hamlet from the perspective of his childhood friends, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, and injects a healthy dose of existentialism into the mix. Born of the same tradition as Waiting for Godot, Tom Stoppard’s script gets away with essentially remixing Beckett’s classic on the sheer strength of its wordplay and the inventiveness with which it applies itself to Hamlet. Its absurdism, after all, is not an imposition on Shakespeare’s script, but an illumination of a philosophical dimension already extant in that original play.

It's because of this understanding that this Rosencrantz and Guildenstern works so well, a thrilling metatheatrical inquiry that always grounds itself in its central duo. Unlike Hamlet, which cycles through its cast of characters, the play continually features Rosencrantz (Sean Close) and Guildenstern (Maboud Ebrahimzadeh), whose delightful odd-couple chemistry anchors the whole affair. Ebrahimzadeh’s Guildenstern prowls the stage with intense rumination; Close’s Rosencrantz probes with more childlike sincerity. As they flip coins, play improv games, and discern the nature of their existence, a bond between the two can’t help but form. They often know nothing of their suffering, save that they must bear it together.

In addition to Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, the traveling theater company that performs The Murder of Gonzago in Hamlet enjoys an expanded role. The whole troupe (featuring Arrianna Daniels, Darin F. Earl II, Ian Higgins, David Andrew Laws, David Pica, Ryan Plunkett, and Damien J. Wallace) operates as a well-oiled machine, each player game for their several parts. Ian Merrill Peakes’s leading player, however, is the performer who most indelibly resonates, commanding the stage with a showmanship as jovial as it is intense. More than any other character, he has accepted the nature of his world and all that comes with it: the fact that everything is a performance, and no performance exists without its audience.

Still haunting, centuries apart

Director Jason King Jones frames these metaphysical episodes on a starker stage than that of Hamlet, as if this play exists within the cracks of its progenitor. All the pieces remain from Hamlet—the wooden structures, the chandeliers—yet at a slightly different angle, warped through a funhouse mirror. At points, you might catch a snippet of a sound cue from Hamlet, as if from another room (sound designed by David M. Greenberg for Hamlet, and by Elizabeth Atkinson for R&G). It is a world that exists perpendicular to Hamlet’s original, one which constantly emphasizes Rosencrantz and Guildenstern’s isolation, forever adrift in a theatrical void.

Taken alone, Hamlet and Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead remain triumphs of their respective eras, still haunting when they take the stage. Together, they amount to something more. The two plays on the same stage seem to reach across time, each shining a light into the dark corners of the other.

At top: Biko Eisen-Martin as Hamlet in Hamlet at PSF. (Photo by Kristy McKeever.)

What, When, Where

Hamlet. By William Shakespeare, directed by Lindsay Smiling. $25-$65. Through August 3, 2025, at the Pennsylvania Shakespeare Festival’s Labuda Center for the Performing Arts, 2755 Station Avenue, Center Valley. (610) 282-WILL or pashakespeare.org.

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead. By Tom Stoppard, directed by Jason King Jones. $25-$65. Through August 2, 2025, at the Pennsylvania Shakespeare Festival’s Labuda Center for the Performing Arts, 2755 Station Avenue, Center Valley. (610) 282-WILL or pashakespeare.org.

Accessibility

The Pennsylvania Shakespeare Festival box office is able to accommodate requests for a wheelchair or companion seat, space for a service animal, a large-print program, or a headset for the assisted listening system. There will be an audio-described and open-captioned performance of Hamlet on Saturday, July 26, at 2pm. There will be an audio-described and open-captioned performance of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead on Saturday, August 2, at 2pm.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Kiran Pandey

Kiran Pandey