Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

The green, green grass of home

John Thompson Morris and Fairmount Park: A love affair

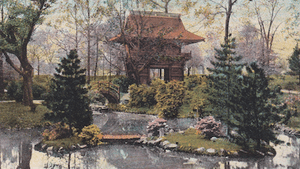

John Thompson Morris's love affair with Fairmount Park was complicated. It began when he was a young man and continued for the rest of his life. Morris certainly had a soft spot for green spaces where everyone and anyone could wander out under the sky. But as much as he wanted his fellow Philadelphians to enjoy the park, he turned a tad stony when too many of them tramped through formal gardens, petted 13th-century wooden dogs at the Temple Gate, and invaded vacant buildings left behind after the 1876 Centennial exhibition. Heaven forbid they should clamber up onto Frederic Remington’s Cowboy.

Morris was quick to notice when things got tattered from too much petting — and was equally quick to take action. He did so in letters to park officials, using an algorithm they would understand: first, identify the issue, bluntly; second, describe the solution, in detail; third, insert rough sketches and calculations where appropriate. When rowdy youngsters damaged his favorite park antiquities, he proposed installing wire cages around them. He suggested building a structure over the Temple Gate to protect it from the elements. He thought it would be wise to dig an underground passageway to Memorial Hall, so guards could move from one building to another.

Good for what ails you

Morris knew a thing or two about the necessity of getting out in the open and catching your breath. Every day until age 44, he was exposed to the fumes and soot of molten iron casting at the family iron works, a hellish process that sucked hot air into flaming furnaces and left behind lung-damaging oxides. Quite possibly it was that toxic environment that made Morris cut his career short, as did his uncle and two older brothers before him. Brothers James and Isaac never found enough air in Philadelphia. They searched for health elsewhere — the Adirondacks, Maine, Michigan, Florida. Both died in their 30s. Uncle John J. Thompson survived into his 50s.

John Morris searched further away: Italy, Egypt, India, Russia, Japan, Norway. He always returned with new ideas for pumping culture into the city’s clogged-up lungs and tucking pockets of refuge into the thick of industry’s din and grime. He had ideas for the placement of adornments of bronze and marble like Stone Age in America, Joan of Arc, and The Medicine Man. Morris made it his business to help turn Philadelphia’s “bare and uninteresting surroundings” into a gallery without walls. Sometimes he even paid for them.

An arrow through the heart

It was costly, loving a park so much, but Morris was smitten. For more than 30 years, he paid due diligence at meetings of the Fairmount Park Art Association and in correspondence with colleagues. Morris implored them to oil the 300-year-old teak of the Temple Gate, to build a fence here, plant a garden there, install a plaque on this statue, dredge that pond. One year, $50,000 was needed to prepare yet another plan binding the bustling city center to its park. Morris was all for it — though, as a thrifty man, he most likely argued that the amount was exorbitant and the association ought to find experts who cost less than Paul Phillipe Cret, Horace Trumbauer, and Clarence C. Zantzinger.

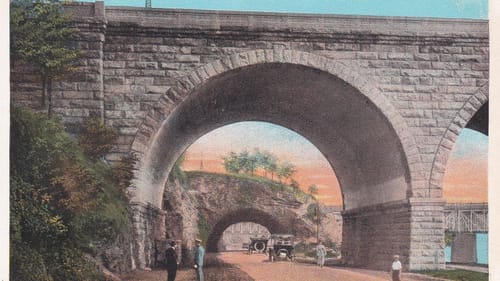

With great exigency, the heart of the city was bisected. Block by block, property was condemned and buildings razed to create an urban thoroughfare. A well-intentioned arrow straight from City Hall led to an imposing art gallery soon to be built at river’s edge, and out the back door to the chasmal park Morris loved. Clustered along its one-mile length, he hoped one day it would be home to a pastiche of institutions, a civic cardiovascular system for conveying art, literature, science, and sustenance to the body politic.

Can’t live without you

On a foggy November day in 1908, Philadelphia mayor John E. Reyburn scouted the route with 100 of his most influential friends and asked: if Paris did it, why not Philly? The mayor pressed his point: “It makes the city beautiful, of course, but this is not all, as it is necessary to the health and happiness of the residents.” Standing near was John T. Morris, a happy resident indeed.

The parkway to paradise was still in the uncertain future when Morris died in 1915. But he left behind his signature on letters appealing to officials to do the right thing by the park. And when Morris spoke, makers and shakers with names like Coates, Cohen, Justice, Steinmetz, and Stotesbury listened. He added another green legacy to the area as well: in 1932, Compton, the summer estate he shared with his sister, Lydia, became the Morris Arboretum.

The attraction continues

Today, Fairmount Park is the sylvan home of 100 sculptures, 25 historic structures, and countless mature firs and shade trees. Beneath the canopy, the West Park’s bygone trolley bed wends its way through brush and thicket, taking hikers over stone bridges and under brick-walled tunnels. Time has muted the summer sounds from the Lemon Hill music pavilion and has made of the East Park reservoir a palmy bird sanctuary. Vestiges of grandeur, glory, and charm are everywhere. It’s enough to make you fall in love with a park.

[Author's note: I suggest reading this piece while listening to “Where Breathing Starts” by the Tord Gustavsen Trio]

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Joyce Munro

Joyce Munro