Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

What did the transformative decade of WWII mean for women artists?

The PMA’s Boom sparks a closer look at women in the art and design of the 1940s

When I first heard about Boom: Art and Design in the 1940s at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA), my spidey sense for women’s history tingled. The museum promised a fresh look at “a period of profound transformation” marked by political, economic, and cultural upheaval against the backdrop of World War II. The preview materials mentioned iconic painter Georgia O’Keeffe and designer Elsa Schiaparelli, war photojournalist Margaret Bourke-White, and abstract expressionist Lee Krasner. I dove in, wondering if this transformative decade marked a shift for women artists in public recognition and canonical art history.

Boom basics

The exhibition (on view through September 1, 2025) offers 240 items selected from PMA holdings by a team of four women curators, helmed by director of curatorial affairs Jessica T. Smith. About 40 percent of the paintings, prints, photos, textiles, ceramics, furniture, and jewelry are on view for the first time. Approximately one-third were made by women or couples that include a woman (e.g., furniture designers Charles and Ray Eames or ceramicists Gertrud and Otto Natzler).

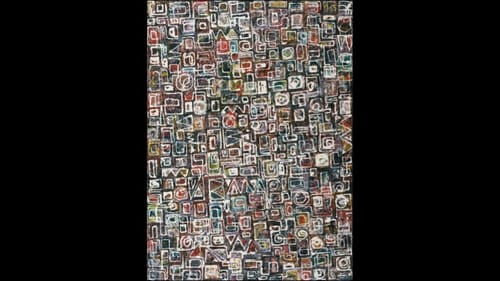

There is a lot of fun and whimsey on display, as well as ingenuity and resilience: a two-piece bathing suit crafted by an unknown home seamstress who repurposed cellulose acetate maps (they held up better than paper maps) leftover from WWII pilots' kits; freeform jewelry by Elsa Freund made of scrap metal and “jewels” of fused clay and glass, avoiding the need for precious materials that were unavailable in wartime. The show also includes sorrow and pathos, as in the photography of Hazel Kingsbury Strand, whose images from Portfolio France – 1945 evoke post-war devastation that could be seen today in Gaza or Khartoum.

Bourke-White, an intrepid photojournalist on assignment for LIFE Magazine in Moscow, captured the first moments of Germany’s invasion in the shimmering Air Raid Over the Kremlin, 1941. But my favorite photos are nonrepresentational: Dream by Lotte Jacobi and Barbara Morgan’s Emanation 1 and Samadhi, from her “Light Drawings” series. Both artists are playing with their medium, abandoning representation and breaking rules, just as many painters, printmakers, and designers did in this decade. Which leads to the most striking development I saw while walking through Boom: the evolution from representation to abstraction, and the style that became known as Abstract Expressionism.

In everything from scarves and ceramics to paintings and furniture, process and materials become the stars. Perhaps the most widely recognized examples of this are Jackson Pollock’s “action paintings” (a term coined by critic Harold Rosenberg). The athleticism of pouring, throwing, and splattering paint was glorified as heroic … at least, when the painter was male.

Progress for women artists?

According to Smith, the Work Projects Administration (WPA) of the 1930s was the first place that women held professional, salaried roles as artists alongside men. A larger pivot occurred in the 1940s, when female artists were taken more seriously, allowed more frequently into art schools, and “included in the professional aspects of art making and production.”

Seeking a benchmark for women outside of art, I chose suffrage. In 1920, the 14th Amendment gave some women the right to vote (in practice, non-white women would continue this fight in the following decades). It’s astonishing to realize that Modernist painter O'Keeffe (born 1897) and Abstract Expressionist Krasner (born 1908) knew a world where they couldn’t vote.

In 1917, the Art Club of Philadelphia launched the Philadelphia Ten, an all-women’s group of painters and sculptors who exhibited and sold art together well into the 1940s. The majority of their work was landscapes, with some portraiture and still life. All of the Philadelphia Ten received professional training at local art schools: two at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and the rest at the Philadelphia School of Design for Women, founded in 1848 and reborn as Moore College of Art and Design in 1932.

The Abstract Expressionism boom

By 1951, 72 New York artists in the budding Abstract Expressionist movement—fed up with the lack of mainstream acceptance—held the Ninth Street Show in Greenwich Village. After deliberating whether including women would reduce their chances of being taken seriously, show organizers allowed 11 women artists to participate. Some of these women happened to be married (then or later) to men in the show.

Over time, a handful of men from the Ninth Street Show (e.g., Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Robert Rauschenberg, and Franz Kline) became “mainstays of museum collections and art history textbooks,” according to The New York Times. Already in 1949, a LIFE Magazine profile of Pollock had asked, “Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?”

But what about the women of Abstract Expressionism? Most often, they were overlooked or belittled as derivative.

Women fight for their place in the movement

A group known as the Ninth Street Women emerged, notably, Helen Frankenthaler, Grace Hartigan, Elaine de Kooning, Krasner, and Joan Mitchell. Though immensely talented, well-trained, and serious about their profession, the Ninth Street Women did not enjoy the embrace of galleries and museums or the rising prices accorded to their male counterparts. Those who were married to fellow Abstract Expressionists seemed to intentionally take a back seat to their partners.

Krasner, for example, was widely acknowledged as her husband Pollock’s most passionate promoter. Once the LIFE article declared his preeminence, Krasner stopped showing her work altogether. It was only after Pollock died in 1956 that Krasner moved out of her small home studio and into the spacious barn Pollock had used, painting on the larger scale she had ceded to him, and gaining greater recognition.

Elaine and Willem de Kooning were another set of Ninth Street spouses. Famously beautiful and charismatic, Elaine took liberal advantage of the pair’s open marriage. However, biographer Lee Hall wrote in her 1993 book about the couple that Elaine slept primarily with powerful men who could further Willem’s career. Hall quotes an anonymous dealer as saying of Elaine, “… God forbid, if she had remained faithful to Bill, the whole history of American art would be different."

For decades, women were excluded from exhibitions of Abstract Expressionism, according to art historian Joan Marter, based on “masculinizing definitions of what constituted ‘originality’.” Finally, in 1987, Marter curated a show at Baruch College to correct the record: Women and Abstract Expressionism Painting and Sculpture, 1945-1959.

Women versus the painting masters

I have a vivid memory of standing in line at the Philadelphia Art Alliance in 1986 when Judy Chicago, founder of the feminist art movement, brought her installation piece The Dinner Party to our city. In his review, the critic at the Philadelphia Inquirer chastised Chicago for not having sufficient talent to take on a topic as profound as women’s power and creativity in childbirth, noting that she would need to be “a female reincarnation of Michelangelo” for such a task.

Today, according to the National Museum for Women in the Arts (whose doors officially opened in 1987), the most expensive painting by a man ever sold at auction is Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi, which fetched $450.3 million in 2017. The equivalent for a woman artist is O’Keeffe’s Jimson Weed / White Flower No. 1, which sold for $44.4 million in 2014, less than one-tenth the price.

Perhaps visitors to Boom can browse other parts of the museum and decide for themselves if women have taken their rightful place in our recognition of great art. Either way, Boom is a fun, accessible show that documents an incredible time of creative fertility and change.

The women behind Boom are Elisabeth Agro, curator of modern and contemporary craft and decorative arts; Dilys Blum, senior curator of costume and textiles; Amanda N. Bock, assistant curator of photographs; Lily F. Scott, exhibition assistant; and Jessica T. Smith, director of curatorial affairs.

At top: A woman’s swimsuit by an unknown maker of the mid-1940s, using a repurposed cellulose acetate map for fabric. (Photo courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.)

What, When, Where

Boom: Art and Design in the 1940s. $35. Through September 1, 2025, at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2600 Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia. (215) 763-8100 or philamuseum.org.

Accessibility

The museum's west entrance on Anne d’Harnoncourt Drive is wheelchair-accessible. Accessible parking is located adjacent to this entrance and in the museum’s parking garage.

The PMA can provide wheelchairs, canes, walkers, gallery stools, noise-cancelling headphones, and sensory kits.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Wendy Univer

Wendy Univer