Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

The magic of accidents

Woodmere Art Museum presents The Photo Review Best of Show

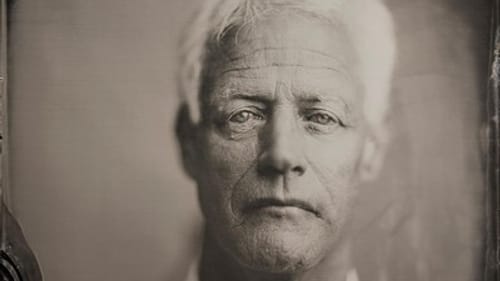

His gaze reaches across the gallery. The stranger with light, penetrating eyes, white hair, and weathered skin in Paul Adams’s large tintype might be a marshal, ready to saddle up and go get his man. In reality, he’s an academic: Kevin J. Worthen, President of Brigham Young University (2020). Instead of depicting Worthen in the dark-suits-on-a-boardroom-wall cliché, Adams presents him “much more authentic and vulnerable.” A person, not a figurehead.

This image is just one of 15 featured in The Photo Review Best of Show at Woodmere Art Museum. They were chosen by juror Christopher James from more than 1,500 submissions to The Photo Review, a locally produced journal showcasing work by emerging photographers, women, and artists of color. James directs the master’s program in photography and integrated media at Lesley College of Art and Design, and is an internationally known artist.

Past is prologue

Without dismissing the ease and precision of digital photography, James champions the creative potential in older, more mercurial ways of making and printing images. “There is a literal hunger for the accident and the imperfect artifacts of life,” he wrote in Visual Literacy: Revolution, Art & Mirrors 2014. “The genre of [alternative process] satiates this need in spades and celebrates, with every attempt, success, and failure, the love of hand-made image and its process.”

The pandemic forced many home-bound photographers back to basics. Matthew Roberts recreated earlier work using low-tech methods—think copier paper, available light, and the kitchen sink. His print Fifth Avenue (2021) could be a battlefield scene from World War I. A pair of bicyclists pedal along, weighed down with backpacks and satchels, as pedestrians move along on the far side of the road. The archival pigment print is sepia-toned and splotchy. Roberts removed all hints of time and place: the background is bleached out, and faces are not visible. The riders might be ferrying takeout to hospital workers or bandages to doughboys at the front.

At home with art

Several images reflect the Great Isolation of 2020. Sequestered at home with her four-year-old daughter, Holly Romano peeked over her child’s shoulder one dinnertime and had an epiphany. Rather than eating the plain pasta set before her, the child made a stick-figure woman on the tabletop (Noodle Art, 2020). “I began to notice how my children revealed themselves to me,” Romano said. “With photography, I examined how they made sense of their identities, navigated evolving relationships, and defined boundaries within our family.”

Abigail Egan shot Home for Christmas (12/25/2019) without knowing it would be the last normal holiday for a while. She recalled thinking at the time, “They enjoy the moment, while I do my best to capture it to cherish later.” Straddling two rooms to catch the glorious confusion of Christmas morning, we see her father trying on a new jacket, mother overseeing a table full of food, brother and sister-in-law sitting with a toddler at their feet, and a second tot climbing into another relative’s lap. It’s an image worth revisiting; maybe it sustained Egan until the next visit home.

Decay and memory

Instead of paper or tin, Laurie Beck Peterson chose a heart-shaped leaf for Three Episodes for Timpani (2021). The work, a delicate and decaying chlorophyll print, is displayed flat in a vitrine. The surface bears a musical score by Peterson’s father for her brother. The staff and notes are almost imperceptible, a spider’s web dancing across the burnished ripples. Imprinted from a transparency, Peterson’s leaf relied on sunlight to expose the notations, and she explained, “My work explores impermanence and the process of growth and decay.” A nearby QR code enables visitors to hear her brother playing the composition.

The best image on view, in Jones’s estimation, is a picture of a memory. In Mémoire Involontaire #5 (2018), Cindy Konits shows us her childhood, or at least, how she remembers it. We’re in a 1950s living room, behind a six-year-old girl watching a black-and-white television. A home movie plays on the tiny, lozenge-shaped screen, and framed family portraits look back from the top of the wooden cabinet. The little girl is sitting, and there’s an empty chair next to her, as though someone has gone, or not yet arrived. A white blur disturbs the picture’s upper left corner—maybe a flare of light, or a blowing curtain, or a person unexpectedly moving into the frame. The work depicts both tangible and dreamy aspects of remembering: the six-year-old Konits watches herself as a baby on the TV, creating a memory of a time the girl probably doesn’t remember, and we stand with the adult Konits, watching both of her earlier selves, a telescope of memory.

When artists let us see

Not all photographic artists revert to old technology, but they do bring an old sensibility to their practice, to a time when photography was rare and magical, requiring black cloths, dark rooms, and potions. They take care, considering what to depict, and how, so that others, who don’t share their perception, grasp the vision. In 2014, Christopher James wrote, “For me, visual literacy is the ability to see.” Artists see, and the best of them enable us to see, too.

What, When, Where

The Photo Review Best of Show. Through October 30, 2022, at Woodmere Art Museum, 9201 Germantown Avenue, Philadelphia. (215) 247-0476 or woodmereartmuseum.org.

Consistent with CDC and City of Philadelphia guidelines, Woodmere does not require proof of vaccination or a negative Covid-19 test for admission. Mask-wearing is optional.

Accessibility

All Woodmere galleries are wheelchair-accessible, with the exception of the Dorothy del Bueno balcony. Accessible parking is available near the Widener Studio building, to the right of the museum, separate from the main parking area. Wheelchairs are available on request. For information and additional assistance, call (215) 247-0476 prior to visiting.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.