Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

The power of public discussion

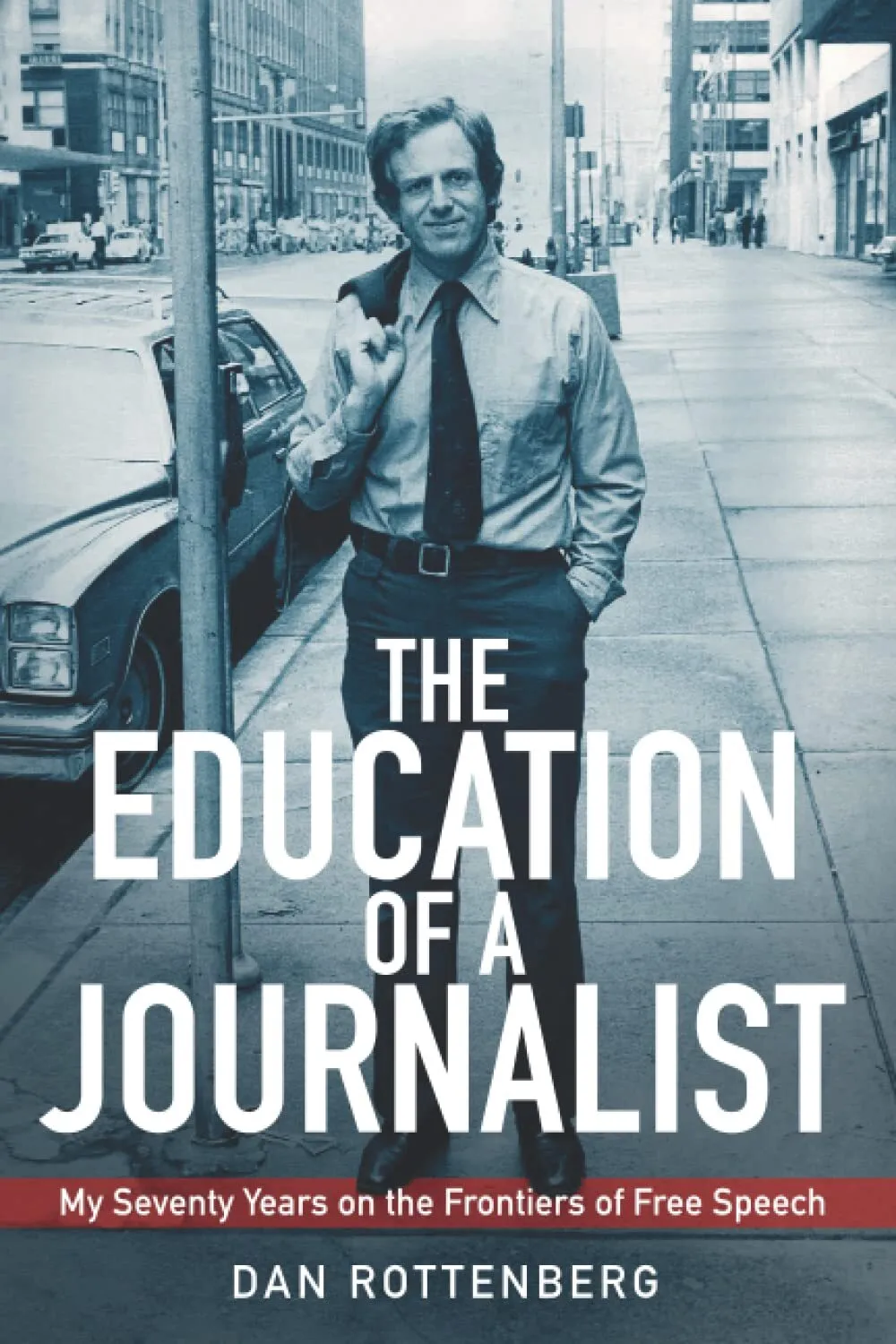

The Education of a Journalist, by Dan Rottenberg

There’s no question that the author of a memoir invites scrutiny of himself as much as any merit that might imbue his work. Dan Rottenberg (the founding editor of BSR) is just asking for it. We’re never very far in his new book, The Education of a Journalist, from a declaration that he invites scrutiny, that he hungers for an audience.

His thick skin has always protected him, he tells us. His belief in the power of debate has always preserved him.

So then, who is Dan Rottenberg? Education offers more than a few clues.

From the age of eight, he has created, edited, and written in numerous publications, through libel suits, in-office protests, boycotts, and never-ending disputation, and has done it with no more fuss than a man closing the drawer of a filing cabinet.

He’s a born reporter, who gets into his subjects’ heads by interviewing everyone who knows them.

He’s a man who sees all sides, and more sides all the time. It’s a restful passage in Education when we are not being reminded that the solution to constricted debate is more debate, that good ideas put the scare into bad ones, that truth sometimes emerges slowly through the conversation. From the very first of these 19 chapters with prologue and epilogue, we hear of Rottenberg’s commitment, sometimes implied and often stated, to the enlightening power of public discussion.

From snowballs to Rizzo

It started in the fifth grade at Public School 9 in New York City, where he took on the principal for threatening to demote students who threw snowballs. It continued at the Portland (Indiana) Commercial Review, the Wall Street Journal, Philadelphia magazine, and the Philadelphia Inquirer, where he wrote an opinion column for many years.

It continued in even greater evidence at the Welcomat and the Forum, in the 1980s and 1990s, where his editorship turned loose all the quiet voices on the sidelines and gave them volume.

So strong was his faith in journalism that it protected the Welcomat against a libel suit brought by then-mayor Frank Rizzo, an in-your-face protest by two dozen members of ACT-UP, who came to his office in 1990 to protest a piece that Rottenberg himself hadn’t agreed with. His gadfly credentials are well in order.

He is able to take us behind the scenes of some local print legends.

Philadelphia magazine, for example, where Rottenberg served several roles for two and a half years, “was not a professional bureaucracy but a uniquely human operation, with all the benefits and drawbacks that term implies.”

This human operation was certainly on display in the relationship of its two primary agents, publisher Herb Lipson and editor Alan Halpern, who didn’t get along. According to Rottenberg,

“To those of us on the editorial staff it seemed clear that Alan made the magazine what it was and Herb was merely a well-dressed figure-head, like Betty Crocker or Colonel Sanders. But one indisputable fact refuted this theory. Alan had edited the magazine since 1951, yet the magazine’s great transformation hadn’t occurred until ten years later, when Herb succeeded his late father as owner and publisher. If in one sense Herb had nothing to do with the editorial product, in a critical sense he had everything to do with it—by giving Alan the freedom and encouragement to pursue his iconoclastic vision. These two men did indeed make an odd couple. But odd couples are often the most interesting couples.”

Awards and relevance

The author would rather stay hungry and humble than rich and famous.

“Had I sought and won more awards, perhaps opportunities to write books or articles would have come my way more easily. But would I have produced better work? I don’t pretend to know the answer, or whether I was right to shun the awards game. I would simply point out that awards—from the Nobel Prize on down—should be taken with a grain of salt.”

He is also a writing machine.

Many were the days I beheld him striding into the office of the Forum ready to trash an already-written column because he had just thought of one more relevant.

I would be hunched over my computer chewing my fingers for my own weekly column, thinking that with a deadline looming and sentences coming at the rate of one or two an hour, relevance seemed maybe a bit too much to ask.

But he would sit and go at it. His eyes would actually light up. It was horrifying.

A modest encyclopedia

He is also a man who has apparently kept every clip and letter that has passed before his gaze, judging by the encyclopedic precision of his dates and quotations. None of this filling up space with literary hooptedoodle. He commands an impressive army of dates and places and arranges them for battle with plenty of reinforcements. His life and memoir are well indexed.

He is also modest, in a well-advertised, billboard-appropriate sort of way. You can’t believe, reading Rottenberg’s own self-dissections, that he would ever fail to acknowledge his own participation in Error, however tenuous or accidental. His postmortems are deft. His mea culpas are designed to prove his point, that however cacophonous our disagreements, something resounding often comes out of them.

When he wrote a column that offended apparently a large percentage of women on the planet, he used the subsequent firestorm to examine every inch of his reasoning and concluded it had been hasty, or at least ill-expressed, and apologized. But even here his response would have been more debate, not less.

The benefits of strife

He is also refreshingly retrograde in management style. Several times he commends the eccentricities of his various locations, the screwballs who worked with him, the mismatched personalities at the top. Who but Dan Rottenberg would ever say that strife in management can make a better publication?

He also provides the example of the sort of journalist we could use in great abundance. He is not afraid of kooks, bullies, puffer-uppers, civil pests, self-helpers, free thinkers, or as he once put it “my own curious crowd here at the Welcomat.” His book is a reference on how to practice journalism in all its haphazard and imperfect glory.

Philadelphia should include on its promotional literature that he lives here.

What, When, Where

The Education of a Journalist: My Seventy Years on the Frontiers of Free Speech. By Dan Rottenberg. Philadelphia: Redmount Press, February 2022. 395 pages, eBook or paperback; $18. Get it on Amazon.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Rob Laymon

Rob Laymon