Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Surprising the eye

The Barnes Foundation presents Alexey Brodovitch: Astonish Me

You may not know Alexey Brodovitch’s name, but you’ve seen his style. Crisp columns of type, lots of white space, scintillating full-page photographs, and magazine spreads in which the look is as interesting as the content—maybe more. The Russian-born graphic designer and photographer changed the presentation of printed matter, both directly and through artists he mentored. His frequent instruction, “Astonish me!” is the title of his first major US exhibition, now at the Barnes.

Brodovitch (1898-1971) is best known as art director of Harper’s Bazaar (from 1934 to 1959), but Astonish Me covers the whole of his portfolio, from early freelance work in Paris, where he settled in 1920 in flight from the Russian Revolution, to teaching, which brought him to the United States in 1930, to numerous side projects throughout his career.

Nurtured by the avant-garde

He could not have chosen a more stimulating Parisian neighborhood than Montparnasse, an avant-garde crossroad and a hothouse for all of the “isms” that reshaped art in the early 20th century, like dadaism, surrealism, and constructivism. Brodovitch flourished there, absorbed what he found useful, and sought work, painting everything from houses to theatrical backgrounds.

Brodovitch’s work from this period includes a whimsical stenciled design, the charming Shepherd with Flute (1922), an elongated figure with arms like the handles on a sugar bowl in a purple jacket and yellow pants. With a pair of sheep as companions and a smiling sun in the sky, he looks like he just ambled out of a storybook.

When Prunier, a Paris seafood restaurant, expanded, Brodovitch designed everything from the menus to the branding. Prunier still exists, and its caviar tins still bear his simple image of layered fish, Fish Composition (Composition aux poisons, 1924).

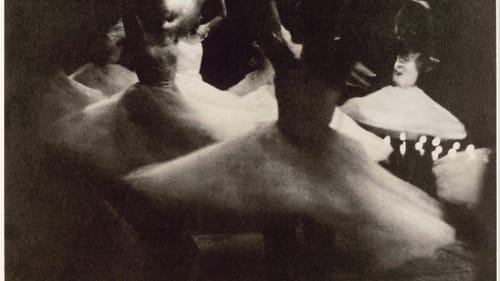

The sensation of dance

While in Paris, Brodovitch painted scenery for Ballets Russe, a relationship that gave rise to a book of revolutionary photographs. In the mid-1930s, when Brodovitch had moved to the United States, he photographed the troupe’s American tour, capturing unguarded backstage moments and rehearsals. Rather than following the typical protocol of exquisitely lit and posed pictures, he used a hand-held camera, available light, a slow shutter, and shot dancers in motion. Brodovitch initially dismissed the blurry, grainy results, but as ideas about photography changed, he reconsidered, printing the images to emphasize their surrealistic appearance and publishing them as a limited-edition book, Ballet (1945), now considered a photographic masterpiece.

Curt Lund of Hamline University, speaking in a 2021 Museum of Russian Art presentation, recalled someone describing “dancers having brushed across” Brodovitch’s film. The photographs convey the sensation of dancing, of seeing dancers flow across the stage. In the Barnes gallery, a digital slide presentation enables visitors to vicariously page through the book.

The Philadelphia connection

Far greater than Brodovitch’s direct impact on the visual landscape was the effect of the photographers and designers he mentored in Philadelphia and New York. Emerging talents, including Garry Winogrand, Richard Avedon, Lillian Bassman, and Diane Arbus, changed expectations for photography and by extension, the appearance of periodicals, books, and other printed materials. The group included those he hired at Harper’s and those he had taught. Brodovitch initially came to Philadelphia in 1930 at the behest of John Story Jenks, a businessman and trustee of the Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art (now the University of the Arts), who wanted him to create an advertising design program.

The Harper’s contingent

Harper’s Bazaar editor Carmel Snow hired Brodovitch in 1934 as art director after seeing an exhibition he’d curated for the Art Directors Club of New York. The magazine’s dated look soon changed. Brodovitch insisted on photographs that surprised the eye, pages with ample white space, and designs in which type and image were integrated for a singular visual effect.

Dispensing with static indoor shots, Brodovitch sent photographers and models into the world to make pictures that looked natural, spontaneous, and frequently startling. Lisette Model, hired for her candid street pictures, would freelance with Brodovitch at Harper’s for more than a decade.

Even those who never saw an issue of Harper’s know Avedon’s famous image of an evening-gown-clad model posing, dramatically but unconcernedly, between two circus elephants. Brodovitch ran Dovima with Elephants, Evening Dress by Dior, Cirque d’Hiver, Paris (1955) at full bleed (to the page edges) and softened the background to sharpen attention on the subject. He created a photographic icon.

Busy scissors

In a 2007 Harper’s retrospective, Jenna Gabrial Gallagher characterized Brodovitch’s photo editing style as “busy scissors." He was an enthusiastic cropper, reducing images to what he considered the essence, a process not always appreciated by photographers. His frequent collaborator at Harper’s, master photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson, abhorred cropping, believing it destroyed proportions. But Brodovitch was an exception: he was the only art director Cartier-Bresson allowed to touch his carefully composed images.

In Calle Cuauhtemoctzin, Mexico City (1934), Brodovitch’s busy scissors made magic. The original and edited versions are displayed side by side. In Cartier-Bresson’s original, two Mexican sex workers are shown looking out to the street, one from a doorway, the other from a window. Brodovitch eliminated the entire right side of Cartier-Bresson’s image, isolating the woman on the left, who leans through the window toward us, almost piercing the photographic plane. Her heavily made-up face is a mask of curves: a curl of hair, half-moon eyelids, upturned mouth. Cropping transformed an interesting picture into one that’s sad, a little scary, and far more impactful.

Finding the surprise

“Surprise quality can be achieved in many ways,” Brodovitch said in a quote referenced by designer Andrew Clarke. “It may be produced by a certain stimulating geometrical relationship between elements in the picture, or through the human interest of the situation photographed, or by calling our attention to some commonplace but fascinating thing we have never noticed before, or it can be achieved by looking at an everyday thing in a new interesting way.” In other words, go astonish yourself.

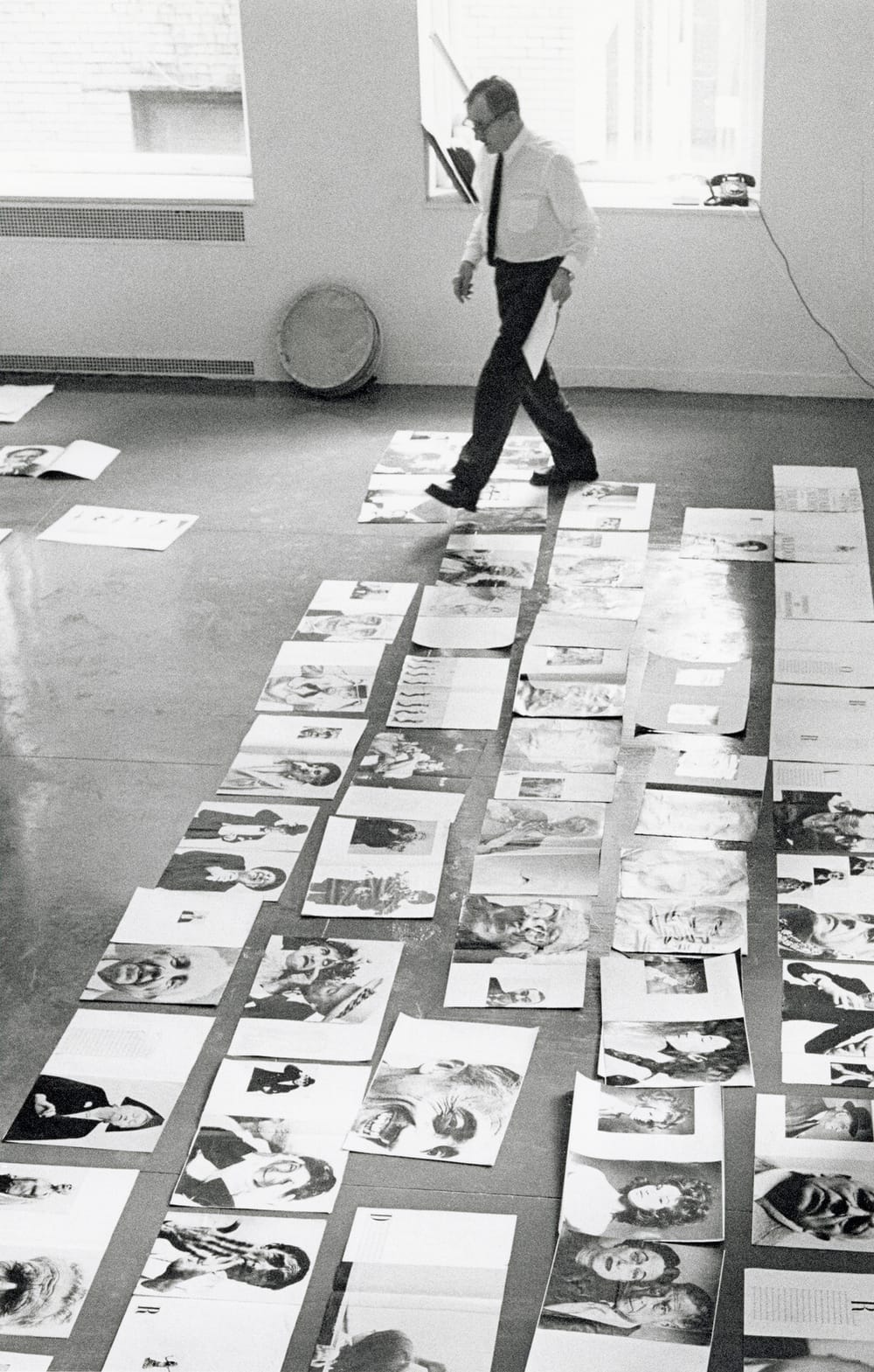

At top: Alexey Brodovitch reviewing page layouts for Richard Avedon’s Observations, 1959. (Photo by Hiro. © 2024 The Estate of Y. Hiro Wakabayashi.)

What, When, Where

Alexey Brodovitch: Astonish Me. Through May 19, 2024, at the Barnes Foundation, 2025 Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia. (215) 278-7000 or barnesfoundation.org.

Accessibility

The Barnes is accessible to standard wheelchairs, and a limited number are available on a first-come basis. Accessible restrooms are located on the lower level and in the Garden Restaurant. Designated parking is available in the lot on Pennsylvania Avenue between 20th and 21st Streets. For more information, see their accessibility page.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.