Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

A knockout exhibition

Philadelphia Museum of Art presents Larry Fink, the Boxing Photographs

In his essay for the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s exhibition catalog of Larry Fink, the Boxing Photographs, former Ring magazine editor Bert Randolph Sugar notes that the sport “recruits from the crucible of the streets boy-men who have fought their way out of the slums, the ghettos, the projects, the barrios, expressing themselves the only way they could… with their fists.”

But behind those hard realities there is a gentle, almost wistful side to the sport. Fink explores this angle in his selection of 80 black-and-white gelatin silver prints from the early 1990s, a portion of a promised gift from Anthony T. Podesta.

“There’s a certain kind of fraternity,” Fink said in an interview with the New York Times. “In the gyms, they beat each other up all afternoon and then they hug all night. They are gentlemen after the tyranny.”

Beauty behind the violence

Many of the photos were taken at Philadelphia’s legendary Blue Horizon gym, which closed in 2010. Others are from occasional side trips to places like Atlantic City and Las Vegas, where Fink shot the setting for heavyweight champion Mike Tyson’s ballyhooed 1991 fight with Donovan Ruddock.

The cast is largely anonymous, its only recognizable figures Tyson and Ruddock; Tyson’s manager, Jimmy Jacobs; promoter Don King; and comedian Eddie Murphy as a spectator. Fink has said he was turned off by the sport’s violence when he was young and got back into it only when assigned a piece on Jacobs.

Fink’s camera spent much of its time on the fringes of the action. The locker room plays as big a role as the ring itself; this is where Fink can best catch the pre-fight tension, joys of victory and pain of defeat. There are some action shots, but nowhere do we see a battered countenance along the lines of Robert De Niro’s Jake LaMotta in Raging Bull or Sylvester Stallone’s Rocky.

The one closeup of a post-combat fighter is ironically titled Silky Smooth. It shows a smiling boxer with bruises and nothing more, expressing a humorous side of Fink that occasionally peeks through. Another shot shows the back of Don King’s head, with its trademark dense graying coiffure.

There are a few shots of female boxers, but no photos of the women actually fighting.

Mano a mano

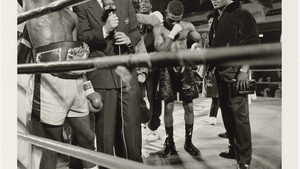

One particularly striking image shows a sportscaster in a corner of the ring after a bout. He interviews a smiling, triumphant fighter as the defeated opponent, flanked by his dejected handlers, stands with his head hanging down in the background. It is a wonderful study of body language.

Another spellbinding image was taken at the Blue Horizon’s fight night. A distance shot shows ceiling lights slicing through smoke and haze to tiny fighters in the ring below and the crowd surrounding them.

And although the boxing world's brotherhood aspects are stressed, no one should be surprised at heavyweight Buster Mathis’s quote, relayed by Sugar in the catalog essay. Annoyed by his handlers’ use of the word we, Mathis said, “Where do they get that we shit? When the bell rings, they go down the steps and I go out in the ring alone.”

Curatorial absence

Curiously, the photos generally lack more description than a year and a location. In most cases, this makes no difference, but it is disconcerting when it would be helpful to identify the general subject.

For example, a photo titled Cutman shows a dapper gentleman in street clothes. He could just as easily be making his living calling on grocery-chain customers rather than furiously patching the face of a battered, bleeding fighter so he can come out for the next round.

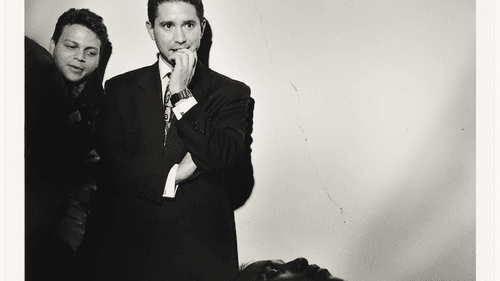

One of the few truly frightening images shows a boxer lying motionless on a table while a man in a coat and tie puts his hand to his mouth with a worried expression. Noting the man’s identity would give the photo needed context.

The minimalist curatorial style might work for an abstract photographer, but that isn’t Fink. Boxers, promoters, spectators, referees, and trainers are real people, as are the “ring girls,” the women who parade across the ring holding up placards announcing the next round.

None of this, of course, takes away from the haunting beauty of Fink’s work. With its portrayal of the odd, almost circuslike cast of characters who make up the boxing subculture, you can see bonds of friendship and solace weaving through the tapestry of violence.

What, When, Where

Larry Fink, the Boxing Photographs. Through January 1, 2019, at the Philadelphia Museum of Art's Perelman Building, 2525 Pennsylvania Avenue, Philadelphia. (215) 763-8100 or philamuseum.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Paul Jablow

Paul Jablow