Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

The wife of a famous woodworker finally gets her due

The Wharton Esherick Museum presents Working at a Joyous Creative Thing: Weaving, Making and Material Culture in Letty Esherick’s Legacy

Cleaning out a closet has never been more worthwhile. Leticia Nofer Esherick (1892-1975) is experiencing a renaissance 50 years after her death, thanks to documents and textiles found at the Wharton Esherick Museum (WEM). In Working at a Joyous Creative Thing: Weaving, Making and Material Culture in Letty Esherick’s Legacy, the museum exhibits newly found weaving and embroidery with contemporary work it inspired.

Letty Esherick’s artistic practice was obscured by that of her better-known spouse, woodworker and sculptor Wharton Esherick (1887-1970), whom she married in 1912, and it was diverted for a time by responsibilities associated with managing a household and raising three children. It was not until the late 1930s, when she separated from Wharton, that Letty devoted herself fully to her craft. The Eshericks remained close and never divorced.

Spread across 12 acres of hills and forests in Malvern, Pennsylvania, WEM was designated a National Historic Landmark for Architecture in 1993. Campus buildings include Wharton’s hand-built studio and Sunekrest, the family’s 19th-century farmhouse.

The threads of a life

Working at a Joyous Creative Thing focuses on items found in 2022 in a closet of the 1956 workshop, where staff discovered two suitcases stuffed with letters, ledgers, and pieces of fabric—handmade and woven, finished and in progress—shadowy hints of an artist’s life.

“These materials … [offer] insight that allows us to position Letty as an important influence on Wharton ... slightly reframing the trajectory of his career as the 'dean of American craftsmen.'”

Jena Gilbert Merrill, then a WEM curatorial and interpretation intern, wrote in 2022: “They offer an opportunity to consider Letty within the broader landscape defined by female craftspeople around mid-century, allowing us to better understand when and how women experienced and accessed professional creative lives.”

The materials, estimated to date from the last 35 years of Letty’s life, became the substance of textile designer and researcher Kelly Cobb’s 2025 WEM residency. Enlisting the support of the University of Delaware’s textile laboratory (which Cobb, an associate professor of the university, directs), she and research assistant Sophia Gupman examined the woven squares and embroidered handmade garments for clues to Letty’s creative approach. Cobb studied the papers for details on the woman behind the works. Finally, Cobb invited contemporary artists to create work inspired by Letty and paired them in the exhibit.

“Kelly and Sophia are among the first scholars to work with these materials, along with Jena Gilbert Merrill,” said Katie Wynne, WEM deputy director of operations and public engagement.

Letty’s woven designs mirrored grids in her gardening ledger, Cobb noticed, and she was fascinated with an overshot pattern known as honeysuckle rose. Cobb, whose practice explores sustainability, also appreciated that Letty’s garments were designed to conserve resources. Now known as zero-waste, the movement echoes conservation concerns prevalent during the artist’s lifetime—for example, during World War II rationing, and in the emerging environmental movement of the 1960s and 1970s.

Collaborating across time

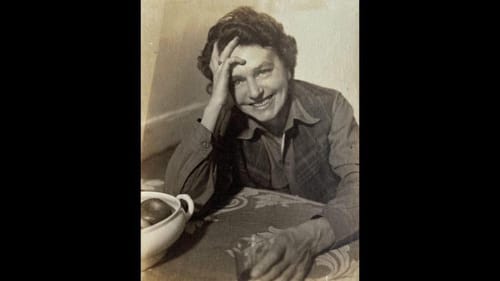

An undated black-and-white photograph shows Letty in a short vest of her own design, but it doesn’t do justice to the garment’s resplendent blend of crimson, aquamarine, pumpkin, and other shades. The vest caught Gupman’s eye: “It’s a plain weave, but how [Letty] uses color is odd—it works, but it doesn’t make sense.” The plaid doesn’t repeat: bands of different colors and widths vary, top to bottom on the vest, but aren’t duplicated. The design so impressed Gupman that she made a corresponding vest using the ikat technique, which involves dyeing (or, in this case, painting) thread before weaving. It’s one of the works on view.

The researchers collaborated on Letty’s Portfolio (2025), an homage to her garden ledgers. The fabric book is covered in a peony print and has colorful threads trailing from between the covers. Other contributing artists include Nicole Feller-Johnson, Abby Lutz, Dana Meyer, Joy Ude, and Eliza Hardy Jones, who referenced Letty’s favorite pattern and her experience in sound design in a sonic weaving, Honeysuckle Weave 24 (2025). The audiovisual work plays softly in the Visitors Center, where the exhibition is displayed (reservations are required to attend WEM).

In conversation with Letty

Letty was a weaver, dancer, and worked across the theatrical crafts. She explored alternative methods of living and teaching, and with Wharton pursued a back-to-nature existence before it became a trend. Both had grown up in Philadelphia and were eager to settle in a rural area, to live on the land and make what they needed. Early in their marriage, they moved deep into Chester County.

Neither favored public education, believing it stifled creativity; Wharton had abandoned studies at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts for this reason. Letty’s interest in establishing an alternative school in Malvern led the family in 1919 to Fairhope, Alabama, where they spent a year at the Organic School of Education. While Letty studied with founder Marietta Johnson, Wharton painted and, when necessity forced him to carve frames, discovered the medium that would redefine his career.

Correspondence offers a window into Letty’s ambitions and frustration at being delayed in full-time practice. Letters to Wharton and others fill in details of her movements from the 1940s on. Though Malvern remained her base, she instructed an occupational therapy program for disabled children and adults in Thiels, New York, and worked throughout North Carolina, weaving and teaching during the Appalachian craft revival. At Media’s Hedgerow Theatre, she took on a variety of creative tasks.

Working at a Joyous Creative Thing represents only a fraction of what was found in the closet, and assessment is ongoing. Though small, the exhibit conveys the sense of hearing from someone who’s been waiting for decades to have a word. The conversation with Letty has just begun.

At top: Detail of a vest designed by Letty Esherick, on view in Working at a Joyous Creative Thing. (Image courtesy of Kelly Cobb and the Wharton Esherick Museum Collection.)

What, When, Where

Working at a Joyous Creative Thing: Weaving, Making, and Material Culture in Letty Esherick’s Legacy. Advance reservations are required to visit. Through December 28, 2025, at Wharton Esherick Museum, 1520 Horseshoe Trail, Malvern. (610) 644-5822 or whartonesherickmuseum.org.

Accessibility

Wharton Esherick Museum is committed to enabling all visitors to experience the museum.

Significant portions of the Studio building, which is hand-built and has multiple staircases, are not accessible to those using wheelchairs or walkers. The Visitors Center, where Working at a Joyous Creative Thing is on view, is equipped with an accessible bathroom. Accessible parking is available in the museum driveway.

Physical elements of the campus are outlined here, and additional accessibility information appears here. For questions, reservations, and accommodation arrangements, contact the museum via email or (610) 644-5822.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.