Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

To see what we’re missing

The Library Company presents Imperfect History

The first image in the Library Company’s timely and provocative Imperfect History exhibition is not even there.

A rectangular frame of gold-painted wood holds nothing but a plain black mat. It’s there in lieu of the library’s first gift in the graphic arts collection, a rendering of an orrery, a mechanical model of the solar system.

The gift was noted in centuries-old director’s minutes—it was a 1733 donation from Thomas Penn—but the image itself is missing. And that gap is the perfect opening for an exhibit that highlights what is absent from the graphic arts collection—indeed, what goes unseen in our nation’s catalogue of visual images—as much as what is there to meet our gaze.

Discovering the Library Company

Though I’m a native Philadelphian, I’d never heard of the Library Company, founded by Benjamin Franklin as the city’s first public library. It’s now a private research institution with a collection that encompasses rare books, written documents, and a 100,000-item graphic arts collection: postcards, sketchbooks, lithographs, advertisements, posters, visiting cards, daguerreotypes, and political cartoons.

This year marks the graphic arts department’s 50th anniversary, and curators wanted to stage something more nuanced than a round-up of “greatest hits,” says Erika Piola, who co-curated Imperfect History with Sarah Weatherwax and Kinaya Hassane.

The election of Donald Trump, the spotlight on “fake news,” and the country’s ongoing racial reckoning made more visible by recent police murders of Black people became the context for an exhibit that examines bias in the creation, collection, and display of graphic arts while underscoring the value of visual literacy, Piola says.

“This was a period of time when cultural institutions were realizing that we were not neutral sites,” she says. “It’s important to be able to read a graphic to understand where we have been and where we are now and where we can possibly be going in this country and in this world.”

Beyond the image

The exhibit’s first gallery, titled “Inception, Collection, and Reception,” offers a troubling—though not surprising—panoply of “where we have been.” Nearly all the pieces, which include etchings, photographs, caricatures, and posters, were created and gifted to the library by white men, who were also their presumed audience.

One of the most disturbing is a hand-colored engraving. Primrose: The Celebrated Piebald Boy, a Native of the West Indies, Publicly Shewn in London 1789 depicts a 15-year-old enslaved boy, John Richardson Primrose Bobey, who had the skin disorder vitiligo and was exhibited as a “specimen of science” from babyhood.

The artist not only objectified Bobey, who is shown front-and-center, with the pale patches of skin typical of vitiligo, but also dressed him in a loincloth, with island images behind him, as if to evoke his “native” origins while erasing the fact of his enslavement.

Again and again, placards offer context and questions that prod viewers to consider what lies beyond the margins of each image: Who created this? For what purpose? How did viewers see it at the time of its making… and how do you see it now?

An 1830 etching, part of a series called “Life in Philadelphia,” shows a dark-skinned Black woman in an exaggeratedly large hat and bustled dress, querying a shopkeeper, “Have you any flesh colored silk stockings, young man?” The cartoon was meant to satirize the attire and habits of Black middle-class Philadelphians, but today, it sears as one more example of the “norming” of whiteness and the daily insults faced by people of color.

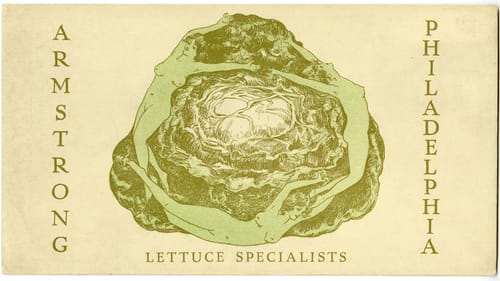

A small vitrine in that first room nods to missing elements of the graphic arts collection; it contains a few items created by women and stands in counterpoint to images in which women are either absent or sexualized, like the produce advertisement from 1915 that includes three nude women incorporated into the ruffled chartreuse leaves of a head of lettuce.

Who decides?

Imperfect History, funded with a grant from the Henry Luce Foundation, includes a print catalogue of images and essays (free to visitors), a digital catalogue with multiple viewpoints on the same images, a curatorial fellow (Hassane, who is now pursuing a Ph.D. in art history at NYU) and, in March 2022, a symposium on the creation and use of popular graphics.

The exhibit spurred me to wonder outside the lines: where, for instance, are depictions of Asian Americans or Indigenous people, aside from one 1804 engraving of Indigenous men being led by a white guide on a walking tour of Old City? Who decides which images are worth preserving? Does the continued display of images with racist stereotypes—even when contextualized and noted as offensive to modern eyes—do more harm than good?

Delight in imperfection

My favorite part of the exhibit was the “Imperfection Section,” which includes materials that contain “flaws”—a scribble across a postcard or an annotation in the margin of a print. In some cases, those notes enabled curators to learn more about the subject, the location or the artist.

One delightfully “imperfect” item is a scrapbook created out of a 19th-century geography book whose owner covered the pages with pockets that resembled dressers and wardrobes, then tucked in paper dolls and their outfits, cut and collaged from fashion magazines: a “defacement” of a dull text by the young artist’s exuberant imagination.

Other items in this section are cracked, water-damaged, torn, worn, stained, or simply faded by time. Not unlike our own still-in-the-making, imperfectly human history.

What, When, Where

Imperfect History. Through April 8, 2022, at the Library Company, 1314 Locust Street, Philadelphia. (215) 546-3181 or librarycompany.org.

Visitors to the Library Company must show proof of vaccination or a negative Covid-19 test dated no earlier than 48 hours prior to visiting. Masks are required regardless of vaccination status.

Accessibility

The Library Company has a wheelchair-accessible entrance, and the Imperfect History exhibit is on the library’s first floor.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Anndee Hochman

Anndee Hochman