Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Making their presence known

The Brandywine River Museum of Art presents Dawoud Bey and Gatecrashers: The Rise of the Self-Taught Artist in America

On view at the Brandywine River Museum through the summer are two widely divergent but equally compelling exhibitions: one featuring photographer Dawoud Bey, and the other a trip through some of America’s most popular self-taught artists, including Horace Pippin and Grandma Moses.

In the intimate Strawbridge Family Gallery, sliding doors glide silently open to reveal 10 remarkable large-format silver gelatin images, hung on dark gray walls, creating a hushed nighttime world that both warns and beckons.

Dawoud Bey: Night Coming Tenderly, Black

These are the photographs of Dawoud Bey (b. 1953) who, over 40-plus-years, has been lauded for images that amplify the presence of those not always included in the American story. Much of his major work has been portraiture, focused on the Black communities of Harlem (where he was born) and Queens (where he grew up).

But these photographs are dramatically different: 10 powerful monochromatic images selected from Night Coming Tenderly, Black, Bey’s critically acclaimed 2017 exhibition at New York’s Whitney Museum. The artist’s first major landscapes, these powerful photographs imagine the 19th-century trajectory of fugitives from slavery, traveling the final leg of the Underground Railroad. Bey shot the landscapes in Ohio moving north toward Lake Erie, with Canada and freedom on the other side.

A resonant choice

Usually, oversized artworks require stepping back to fully appreciate them. But here, the serene installation’s contemplative oasis asks the viewer to draw near and look closely, immersed in Bey’s compositional mastery. Some images have a visual foliage “screen” to peer through, while others lead the eye diagonally via mysterious white farm buildings, fences, or streams, rendered in velvety textures of grey and black. People, mysteriously present by their absence, are made tangible by houses and fences glimpsed from a lowered point of view, as a crouching fugitive might see them. And since these secret historic pathways were never clearly delineated, Bey could give his imagination full range. Each image carries both the promise of safety and the fear of discovery that fugitives must surely have had to balance each night.

The exhibition is a resonant curatorial choice since the Brandywine Valley was populated with major Underground Railroad stations. The museum has acquired Untitled #24 (At Lake Erie), a magisterial work with its glimpse of that enormous body of water—the final obstacle to freedom—shrouded by foliage. This beautiful photograph may be on future view, but this exhibition, powerful in its thought-provoking majesty, can only be experienced now. It runs through August 31, 2022.

Gatecrashers: The Rise of the Self-Taught Artist in America

The Bey exhibition is intimate and reflective, but Gatecrashers is expansive and stimulating, fueled by scholarship and curiosity. Curated by Katherine Jentleson of Atlanta’s High Museum, where it originated, it features more than 50 works exploring how in early-to-mid 20th-century America, artists without formal training “crashed the gates” of major museums to diversify the art world “across lines of race, ethnicity, class, ability, and gender.”

Jentleson’s surprising and somewhat curatorially audacious view is that in their time, these artists were a highly regarded sector of American art. But in the 1950s, the importance of their work (and their legacy) was diminished, written out of the artistic mainstream by the overwhelming intellectual opinion of critics who contended that abstraction was the true representation of contemporary American art.

John Kane

The gallery opens with a painting by each of the three most celebrated “gatecrashers”: John Kane, Horace Pippin, and Mary Ann Robertson “Grandma” Moses. The exhibition title came from press coverage of John Kane (1860-1934), a Pittsburgh painter who caused a sensation as the first living American self-taught artist accepted for the highly influential Carnegie International. Kane had come to America from Scotland to work on railroads in Western Pennsylvania, but when he lost his leg in an accident, he shifted from manual labor to painting.

In 1927, when Kane entered Scene from the Scottish Highlands (mysteriously featuring his ghostly brother), Carnegie jurors were skeptical. But well-known artist Andrew Dasburg (on the jury) vowed to vote out any other painting if Kane’s work was not admitted. Kane led a Pittsburgh school of painting tied to a burgeoning interest in American regionalism, paving the way for other self-taught artists, some on view here.

Horace Pippin

Next is Horace Pippin (1888-1946), the West Chester artist well-known in the Philadelphia region. In World War I, Pippin served in the segregated 369th Army, and after he was wounded in 1918, he began making art to rehabilitate from his injury. The exhibition opens with his first major work: Ending the War, Starting Home, 1930-1933. As well as creating a moving depiction of his experience, Pippin made its remarkable frame, decorated with the ephemera of war. This painting (too fragile to travel to Atlanta) is new to the exhibition, loaned by the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Pippin first showed his work in 1937 at the prestigious Chester County Art Annual that included leading contemporary artists. There, his paintings were somewhat sidelined, but artist John McCoy introduced them to N.C. Wyeth and encouraged the show’s curator to give Pippin prominence. His work was quickly embraced by Albert Barnes, and Pippin—one of the only African American artists embraced by both the white establishment and the Harlem Renaissance—was also part of the 1938 Masters of Popular Painting exhibition at MoMA.

Grandma Moses

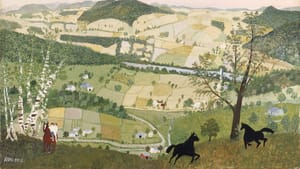

The third “focus” painting is Hoosick Falls in Winter (1944) by Anna Mary Robertson “Grandma” Moses (1860-1961). Due to the demands of her upstate New York farm, Moses returned to artmaking late in life after her husband died, first creating in wool embroidery. She then turned to painting, showing work at the 1938 Cambridge County Fair and in the window of a Hoosick Falls pharmacist. A New York City collector who stopped at the pharmacy bought all her work and took it back to well-known gallerist Otto Kallir, whose fondness for folk art led to a 1940 gallery show.

Moses was highly celebrated by both art museums and in American homes (via publications like Life magazine). She was seen as a significant American artist, and her Paris exhibition that toured through Europe met with tremendous positive response, annoying art critics who felt she was eclipsing “their” American abstract artists like Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning.

Gatecrashers is divided into seven curatorial sections, with works by Kane, Pippin, and Moses, along with 21 other self-taught artists (now lesser known but recognized in their day). Brandywine curator Audrey Lewis coordinated the exhibition, running through Labor Day.

What, When, Where

Dawoud Bey: Night Coming Tenderly, Black (through August 31, 2022) and Gatecrashers: The Rise of the Self-Taught Artist in America (through September 5, 2022). Brandywine River Museum of Art, 1 Hoffman’s Mill Road, Chadds Ford, PA. $6-$18 (free for kids under six-years-old). (610) 388-2700 or brandywine.org.

The Brandywine River Museum of Art follows CDC and PA Department of Health guidelines. Masks not required in the museum (but are required for touring Wyeth studios) and are available at the Visitor’s Desk. Timed tickets are required (except for museum members).

Accessibility

The Brandywine (including the café) is wheelchair-accessible, with accessible parking, a barrier-free entrance, and available wheelchairs.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Gail Obenreder

Gail Obenreder