Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Courage that inspires us today

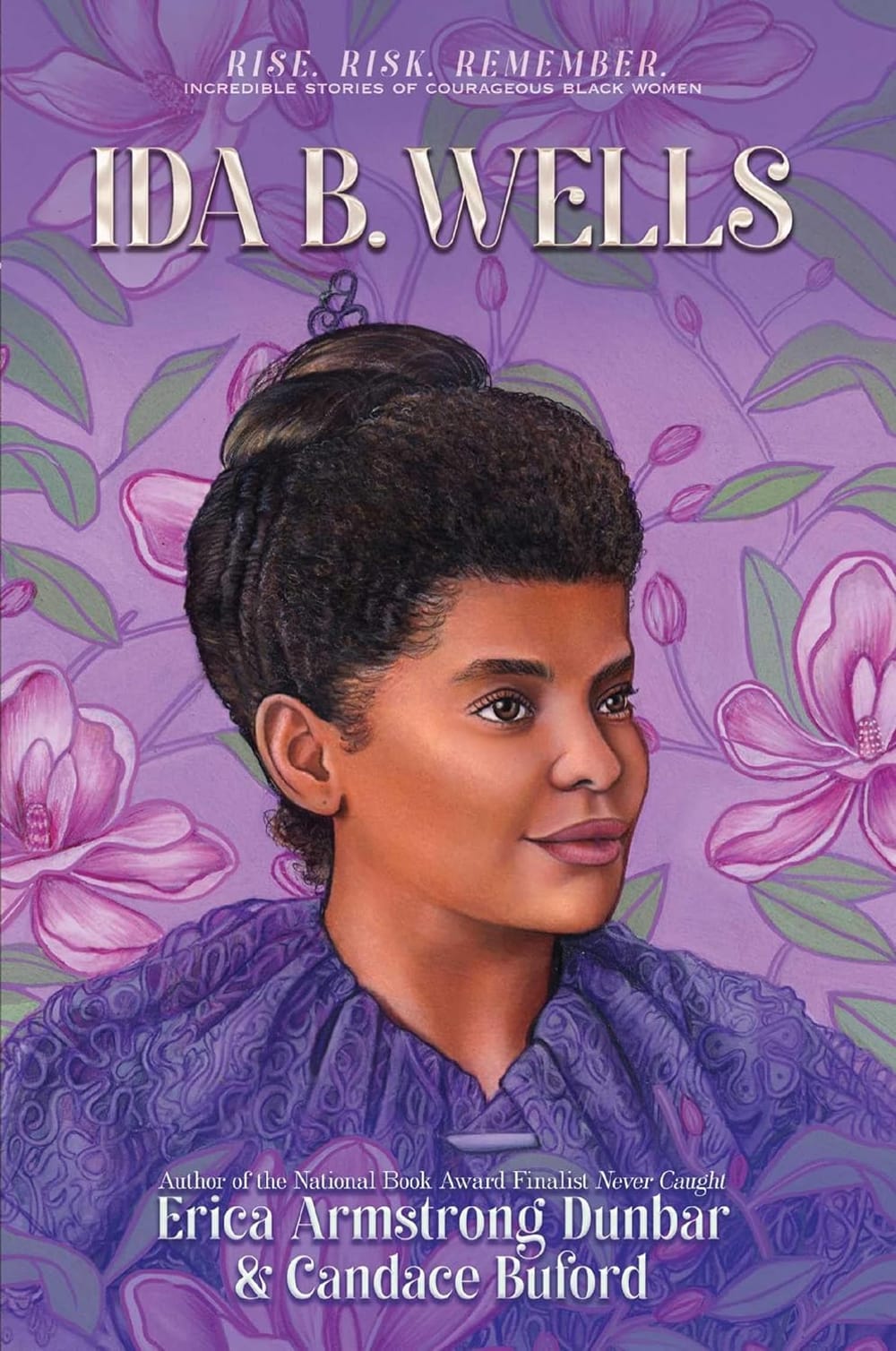

Ida B. Wells: Journalist, Advocate, and Crusader for Justice, by Erica Armstrong Dunbar and Candace Buford

Ida B. Wells (1862-1931), a fearless, hot-tempered Black activist, risked her life to oppose lynching, met with President William McKinley about that issue, co-founded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), launched Chicago’s first Black kindergarten (considered an innovation in 1897), and much more.

Often dismissed during her lifetime, she has received posthumous honors, such as the 2020 Pulitzer Prize for reporting on lynching. Now, historians Erica Armstrong Dunbar and Candace Buford have teamed up on a new biography for young people that does Wells’s teens and early adulthood justice. Dunbar, a Penn alum, Rutgers history professor, and the author of Never Caught, studies the lives of women of African descent in 18th- and 19th-century America.

A historic activist

The book invites readers into Wells’s life in her hometown of Holly Springs, Mississippi. In an 1878 scene, her father, a carpenter born into slavery and freed by the Civil War (like Wells herself), returns home from his shop. He carries the scent of sweat, sawdust, and wood stains. Within weeks, a yellow fever epidemic ravages Holly Springs, killing Wells’s parents and her baby brother. Wells, away visiting her grandmother, escapes the illness. At 16 and the oldest of the seven surviving children, Wells decides to become head of the household. She leaves college and takes a teaching job. With her salary and the help of relatives and friends, she succeeds in keeping the family together.

The biography highlights other defining moments in Wells’s life. After her move to Memphis, readers see her progress from teacher and general-assignment journalist to fierce anti-lynching activist after a white Memphis mob kills her friend, successful Black grocery store owner, Tommie Moss, in 1892.

A first-person view

Dunbar and Buford present Wells’s story from a first-person point of view, letting readers see events as Wells saw or lived them. “Whenever possible, we draw on Ida’s own words,” the historians write in the book’s introduction. They also use “informed speculation,” making educated guesses about Wells’s outlook when her diaries, letters, pamphlets, and editorials don’t address a situation directly.

The first-person approach lends cinematic sharpness to events. One senses the weight of the gun Wells carries after white people in Memphis threaten to kill her for writing anti-lynching articles. Readers watch through Wells’s eyes as Black families scramble to cross the rain-swollen Mississippi River when they leave Memphis after Moss’s murder.

While the first-person point of view intensifies readers’ experience, one expects to hear the story in a well-bred Southern Black voice of the 1880s or 1890s, the era that most of the book covers. For that reason, words and expressions from the 2020s, such as “enslaver” and other contemporary expressions, feel jarring.

In her own words

Dunbar and Buford make the wise choice to concentrate on Wells’s early life, the years with which young people will most identify. An epilogue telescopes readers to Chicago in 1923, where Wells looks back on her marriage to Ferdinand Lee Barnett, motherhood, and other accomplishments in her middle years.

The biography includes one of Wells’s best-known works, Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases (1892), prefaced by a letter from Frederick Douglass. “We feel it is important not only to know Ida’s story but also to read her own words,” Dunbar and Buford write. This decision paints a vivid picture of the era in which Wells lived.

Lynch Law pulls no punches. It emphasizes that white mobs lied, saying that white women had been raped by Black men, in order to justify killing the men. The truth, Wells writes, is that white communities used lynching as a form of racial terrorism to punish Blacks for success in business and politics. Wells also points up a sexual double standard in the South that deemed it acceptable for white men to have Black mistresses but howled when white women had Black men as lovers.

Perfect timing

Ida B. Wells: Journalist, Advocate, and Crusader for Justice provides an excellent account of this activist’s life for more mature young people. (Younger readers might enjoy Dinah Johnson’s 2024 book, Ida B. Wells Marches for the Vote.) Dunbar and Buford’s book comes at the perfect time. This biography shows young folks—and people of all ages—what a courageous person can accomplish even under harsh circumstances.

What, When, Where

Ida B. Wells: Journalist, Advocate, and Crusader for Justice. By Erica Armstrong Dunbar and Candace Buford. New York: Aladdin, June 3, 2025. 208 pages, hardback ($19.99) or paperback ($8.99). Get it here.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Constance Garcia-Barrio

Constance Garcia-Barrio