Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

The stories we told ourselves in Philadelphia

Exploring the new early American galleries at the Philadelphia Museum of Art

Early American art—from 1650 to 1850—was like a foreign country to me. But as Kathleen Foster, the Robert L. McNeil Jr. senior curator of American Art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, led me through the PMA’s re-visioned galleries, the story of art, culture, and wealth in Philadelphia unfolded around me.

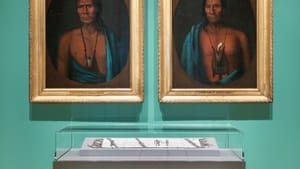

The first gallery opens with portraits of the Lenape chiefs Lapowinsa and Tishcohan, by the Dutch painter Gustavus Husselius, the first professionally trained European artist in America. “It is really about this encounter of great civilizations,” Foster said. It isn’t a happy story; the portraits are grave and stately, and the eyes are sorrowful. The paintings mark the 1737 treaty with Penn’s sons that cheated the Lenape out of their land; these pieces now hang above the wampum belt marking the first meeting of Penn and the Lenape, marking images of promise and betrayal before viewers are well past the door.

The workings of wealth

We usually think of art as paintings and statues, but before the mid-19th century, the story is mostly decorative objects—furniture, silver, porcelain. And because the first portrait daguerrotypes aren't made until around 1840, most of the paintings in this collection are pieces that effectively functioned as family photos.

When I asked what made furniture art, Foster said, “We love to think of furniture as sculpture.” But silver was wealth: money you could make tea in until you needed the cash. Like a bank, but shiny. According to Foster, silver began its multinational journey in Potosí, Bolivia, where it was mined with enslaved or forced labor and cast into ingots or coins for shipping through Havana to Spain. There the ingots would also be made into coins.

“Bags of the coins would have gone to New York and Philadelphia and Boston, the great silver-making centers," Foster explained. "You would go to the craftsman, hand them a bag of coins and say, ‘I want a tea service for my daughter’s wedding.’” Foster said that is one reason old silver is hard to find. A daughter could trade in that tea set for the value of its weight in silver—a fungible asset that likely travelled with women. Or she might have it remade in the new Rococo style.

The Athens of America

At the turn of the 19th century, Philadelphia was the nation’s capital, often called the Athens of America for its urbane culture. The Latrobe parlor, created by the architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe for William and Mary Waln, gives a glimpse of how the wealthy and fashionable lived in 1808. William made his fortune shipping opium from Turkey to China. Mary spent his fortune on an extravagantly decorated house on Chestnut Street. This is furniture as art, Greek Revival with an exotic flair. The low divan, in gold, sports a tassel fringe (fabrics recreated from clues found in the threads caught under the nail heads) and chairs with decoratively painted backs replicate the versions one sees on Grecian urns.

“This is more avant garde than Paris,” Foster said. A dress form behind the divan wears a white late-Georgian dress. “We wanted to personify Mrs. Waln, to have her in her parlor, and make you think about her entertaining.” Nearby are Peale portraits of her parents, another story of Philadelphia as a center of art and culture.

The Peales of Philadelphia

Charles Willson Peale was one of the most famous portraitists in America, but it didn’t pay all that well. While we admired Peale’s portrait of General Cadwalader and his family, Foster noted that “[Curator] Alexandra Kirtley has found the receipt—the frames cost more than the paintings.”

The whole Peale family hustled at the painting game, including the Peale women, who, Foster said, “were the first women to earn a living as artists in the country.” But visitors always stop at the Staircase Group, a full-length portrait of two young men on a staircase. It’s installed just above a real step to fool the eye, and Foster shared a curatorial curiosity. “When we took the painting out of the wall, the conservator realized that it had been stretched crooked on its stretcher 50 years ago.”

The young man at the top of the stairs had his finger cut off by the mistake, and Foster said the conservator “had to take it off the stretcher in order to get his fingertip back. The painting was first installed at Independence Hall, in an exhibition in 1795, where he would have been pointing to the Peale Museum.”

Foster noted a ticket painted as if it had been dropped on the stair. “This is a ticket to the museum. So the whole thing is an advertisement for his boys. This is Raphael Peale, the still-life painter, who’s just launching his career, and Titian, who is a naturalist.” The names clearly reflect Peale’s aspirations for his children.

The free Black community

Pennsylvania abolished slavery in 1780, and perhaps ironically, although the last enslaved people here were not freed until the 1840s, by the 1790s Philadelphia had the largest free Black community in the country. Among them was Thomas Gross, a cabinet maker. Signed furniture by Black craftsmen of the time is vanishingly rare, but on the bottom drawer of one high chest in the collection, Foster points out Gross’s “fabulous, flamboyant signature.” The museum left the drawer in place, but made a facsimile so we could see the elegant signature.

A pair of wedding portraits drew my attention—Hiram and Elizabeth Montier, painted around 1841. According to Foster, Elizabeth Montier descended from Richard Morrey, the son of the first mayor of Philadelphia. Richard Morrey’s common-law wife was Black and Native, Foster said. “He acknowledged her as his wife—Cremona was her name—and when he died, he left her hundreds of acres in Jenkintown.” A hundred years later, a descendant of this prosperous, landowning Black family commissioned the portraits.

Not “peaceable”

The exhibit ends with an 1826 painting from Edward Hicks’s The Peaceable Kingdom series, depicting Penn’s first meeting with local Natives, juxtaposed in the PMA presentation against a display of Lenape beadwork. “This is from 150 years after the wampum belt,” Foster explained. “Native Americans were still making beautiful beadwork, but [the Lenape] had been pushed to Kansas and Oklahoma.” The Hicks paintings, she said, “are being used as this mythology about Philadelphia, when in fact we treated them very badly.”

Early American art in Philadelphia is a hard story to tell. It begins in treachery and ends just as the last enslaved people are freed. But with the newly installed galleries, the PMA takes an important first step in rethinking the story we tell about ourselves through our objects.

Image description: A gallery view of two side-by-side portraits of Lenape chiefs Lapowinsa and Tishcohan, by Gustavus Husselius. The wall behind is pale green and below is a gray table with a beadwork display.

Image description: A view of the Latrobe parlor on display at the PMA. It has an ornate fireplace, table, chair, and couch, and the color scheme is black, rust, gold, and light blue.

Image description: A photo of a wampum belt made by Lenape women in the 1680s. It’s white with three diagonal black lines, and two black human figures with their hands joined.

Above: An installation view of the early American art galleries featuring the "Wampum belt," 1682, likely made by Lenape women artisans. Made in the Delaware Valley. Above, on the left, "Portrait of Lapowinsa," around 1735, by Gustavus Hesselius. Oil on canvas, 33 x 25 inches. Above, on the right, "Portrait of Tishcohan," around 1735, by Gustavus Hesselius. Oil on canvas, 35 × 25 inches. On temporary loan from the Board of Trustees of the Atwater Kent Museum (Philadelphia History Museum), the Historical Society of Pennsylvania Collection, and the City of Philadelphia. Image courtesy of Philadelphia Museum of Art. Photo by Joseph Hu.

What, When, Where

The Robert L. McNeil Jr. Galleries of early American art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. 2500 Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia. 215-763-8100 or philamuseum.org.

Covid safety: Currently, tickets must be reserved in advance online for timed entry to control the number of visitors. All staff and all visitors over age 2 must wear a face mask and practice social distancing. Hand sanitizer units are available throughout the building, and high-touch surfaces are cleaned throughout the day. Detailed information is available on the museum's website.

The PMA is a wheelchair-accessible building. Complete accessibility information is available here.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Camille Bacon-Smith

Camille Bacon-Smith