Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

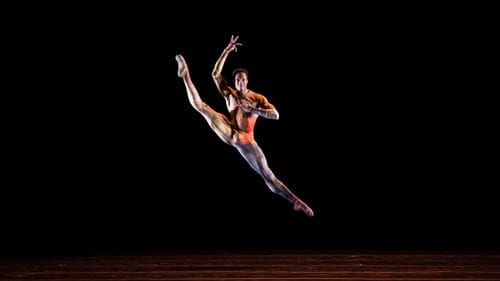

Where do dancers discover themselves?

Philadelphia’s Black male ballet dancers share their journeys to the stage—and what the future may hold

“As a child seeing ballet, I thought it was only for white people, because I didn’t see myself represented,” said Ramón Flowers at a February 12, 2022 panel discussion featuring Black alumni of the Philadelphia Ballet. Flowers, the company’s first Black male hire, said he almost didn’t become a ballet dancer.

As a student, he loved musical theater, and when a college teacher advised him to take some ballet lessons to clean up his lines for show dancing, he fell in love with it. “You can tell when something is innate when you are exposed to it, [and] what it might mean to you.”

Flowers, who joined the company under artistic director Robert Weiss, left for Europe after Weiss was fired, as did fellow dancer and panelist Joseph Malbrough—demonstrating that as recently as the 1980s, Black dancers felt they had to leave the United States for opportunities. I wanted to know if things had gotten better. The answer, not surprisingly, is complicated.

"I can do this?"

Fellow panelist Meredith Rainey originally planned to be an architect. A girlfriend and a guidance counselor convinced him to try out for dance at the Arts Annex at his high school. It was a transformative experience, he said: “When you don’t know that you have a talent, and then all of a sudden somebody shows it to you, it’s kind of shocking. It’s like, ‘I can do this? Oh my gosh!’” From then on, Rainey was a dancer.

I reached out to BalletX’s Pete Leo Walker, who was taking breakdancing classes when his teacher suggested that he try some ballet to improve his breaking skills. The company’s rising young dancer, Shawn Cusseaux, added that he auditioned for everything at his local arts high school. He thought his dance audition was terrible.

“I just frolicked around the room for two minutes until they finally stopped the music (Adele’s 'Rolling in the Deep') and said thank you.” Dance teacher Patricia Page Parks pulled him out of his drama class and told him to try dance instead. She saw something in the way he moved that he didn’t know he had.

Without public arts high schools and teachers who drew them to dance, we might not have Rainey, or PHILADANCO! alumni Tommie-Waheed Evans and Joe González, or BalletX’s Cusseaux on our stages. But Black men often come into these programs already behind, with limited early training, because classes are expensive or not available in Black neighborhoods.

It's a story I heard over and over. To become dancers, kids have to know they are included. In recent years, local companies from ballet to tap have brought dance into the public schools, and PHILADANCO! hosted a matinee at the Kimmel. But as artistic director Kim Y. Bears-Bailey said, “These schools have to be supported by funding that allows them to bus kids in to see concerts and it is just unfortunate that the arts always are the first thing to get cut.” The pandemic has made outreach even harder.

Bodies and stories

When I talked to González about his experience with PHILADANCO!, he said that his body type and size—bigger than most dancers—led to a lot of unsuccessful auditions. But at PHILADANCO!, “there was this sense of embrace.”

“Some of my lines look different” than, for example, a Prince Charming-type role, Philadelphia Ballet’s Jermel Johnson said. “I have a lot of power in my legs and usually you see guys that are leaner as far as the lines and the aesthetic.” He’s been getting more of those roles. But even now, new dancer Cusseaux worries about putting on muscle. We cannot have diversity if we don’t celebrate diverse bodies.

PHILADANCO! has been presenting Black stories since its inception, of course, and BalletX has a diverse cast and repertoire. Evans is one of many Black choreographers who have created works with the company, and he loves working with them.

“I do love what Christine [Cox] has done with BalletX. I said I want to use [minimalist composer] Steve Reich, and she’s like, ‘Of course. Go for it.’” He contrasted this with other companies who limit his scope in ways they would not for a white choreographer, saying things like, “Oh, no, I see you for us doing this so you can teach us your Black sensibilities.”

An education about dancing

Similar concerns were visible at the Philadelphia Ballet panel. A board member asked if the panelists could see themselves in the most recent program, though none of the dances had been choreographed by a Black choreographer. Moderator Virginia Johnson, artistic director of Dance Theatre of Harlem, had some words.

“This is not a criticism of your question, but it’s an education about what it is to be a dancer,” she explained. “If you want to talk about the works that we saw, and are these works going to tell us about a future that is diverse in this country, perhaps not. Perhaps there could have been more of a reflection of a broader aesthetic in the works. But don’t ask the dancers do you relate to it, because we all did, like wow.”

Her comments speak directly to what it means to be a dancer drawn to this art form: Black dancers can love it all, and dance it well, from stories that arise out of the African American experience to the 19th-century romantic ballets, which Rainey called museum pieces, while admitting they are beautiful and should be seen. Should they be re-visioned in some way? Perhaps, but Rainey himself choreographs in the neoclassical style. As Evans pointed out about dancers like himself, “you don’t get to be Romeo,” but a Black Romeo gives the ballet new relevance. West Side Story has been showing that for generations.

Future challenge, future hope

Dance needs dancers like Flowers and Rainey, González and Johnson, for their talent and their passion. But there just aren’t that many young male dancers out there right now, and many come ill-prepared. According to Bears-Bailey, “We’ve had three male auditions, and we can count on two hands how many people have been there, when sometimes [in the past] we would have to turn people away at the door.” She says this shift was underway before the pandemic.

She thinks male students need to see more of themselves, on the stage, in the rehearsal rooms, and in classes: “They have to see it. They have to see it to be inspired by it, just like young girls are.”

My sources repeated a similar story—being the only Black student, the only male student, in a class. Cusseaux said he was in college before he realized how many Black dancers there were. Covid-19 compounds the problem: class attendance is declining, and the pandemic will leave a gap that is going to be hard to recover from.

Bears-Bailey sees a mentorship gap: older dancers who show that it can be done, and guide new dancers on their journey. But she admits that it is harder now for boys. “I think the peer pressure is probably different for young guys than it was 20 years ago. If you are a student and your dad didn’t support you, you had a couple buddies that were, go ahead man, do what you do. Now it’s survival. It’s really sad. It’s survival.”

Despite all this, Evans concludes on a hopeful note: “Follow your dreams. Be bold about your dreams. Speak your dreams out loud.”

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Camille Bacon-Smith

Camille Bacon-Smith