Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

The brainiest room in the world

Treasures from the Bodleian in New York

There’s the Cloud, and there’s the Library.

The enormous complexes around the country that service the data-storage empire called the Cloud look like UNIVAC-sized monsters (despite their fantastically compressed digitization) disguised as the innards of alien spaceships. Their goal is to contain Everything. This they accomplish by electronic amalgamation, which you must unscramble by codes before you can access any given item. Thus, the Cloud can aspire to being a universal repository while, without the proper key, it’s nothing at all.

You might say that a library — or, for that matter, the human mind itself — functions similarly. Without a catalog, a library is largely useless. Without memory — itself an ingenious example of circuitry — the mind can’t function. It’s all about information retrieval.

Yes, but.

The terrifying thing about the Cloud is not its ubiquity but its vulnerability, or rather, one might say, its combination of both. Where everything is collected in one place it is theoretically accessible to all, given the right server. This seems like a great victory for democracy in principle, unless you reflect that the National Security Agency, which wants to know everything, also wants to reveal nothing. That makes privacy a thing of the past, without which there’s not much left of democracy either.

Can books sing?

The biggest problem, though, is that where everything is collected in one space, it is not only easily controlled but also easily destroyed, especially in electronic format. That’s why “backup” (another word for dispersion) is such a constant issue in the computing world.

Which brings us to the Book.

Books are hardy objects. They degrade slowly and take some effort to destroy. Also, they’re not disaggregated bundles of randomly assembled information. They’re the very opposite: highly focused, precisely rendered creations that can embody human grace, intelligence, emotion, and personality as nothing else can. They can also be extraordinarily beautiful as objects, through craftsmanship, calligraphy, fine printing, and illustration. They can do about everything except dance and sing — and if they happen to contain musical scores or labanotation, they enable us to do those things as well.

For these reasons, people go to exhibits of books simply to look at them rather than to read them. Sometimes they prize their rarity, sometimes their beauty as visual art, sometimes their cultural significance, sometimes all three. For these reasons, you won’t find a more amazing room in the world right now than the gallery at the Morgan Library that offers a selection of masterpieces from Oxford’s Bodleian Library.

From a Cairo garbage dump

The Morgan itself is no slouch in the book department. But the Bodleian is one of the world’s oldest and greatest libraries, and it has lent the Morgan some of its most extraordinary treasures, including its manuscripts and maps.

The most ancient of these are the oldest surviving papyrus fragments of Sappho. They date from the second century C.E., and were recovered from a garbage dump in Cairo in the late 18th century. They aren’t in Sappho’s own hand, of course — she flourished about 700 years earlier — but as the closest thing we have to it, they seem an icon of poetry itself.

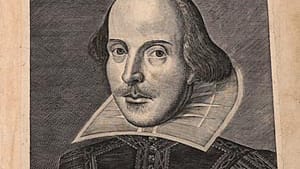

The Bodleian has also put England’s best foot forward. There’s a 1217 copy of the Magna Carta, the set of concessions wrested two years earlier from the authoritarian King John by his barons, and the cornerstone of the Anglo-American legal tradition that Barack Obama and David Cameron are so freely casting to the winds these days. There’s a Shakespeare first folio, which was presented to the Bodleian in 1623, sold by it when the third edition came out some 40 years later, and only recovered when it miraculously came on the public market in 1909 through a national subscription campaign. And there’s a first edition of Newton’s Principia Mathematica, the foundation of modern physics and astronomy. Those two books and that stiff parchment are not only the glory of a nation but also the core of genius and principle on which much of modern civilization rests.

Shakespeare’s Bible

The Morgan show ranges around the world, though, from the description of the New World in the Codex Mendoza to an 18th-century edition of the Bhagavad Gita, printed on thin, scroll-like strips in the fashion of late Mughal India. There’s a splendidly illustrated edition of Boccaccio and a 14th-century Romance of Alexander, based on the conqueror’s legend.

The major display categories are literary, religious, and geographical/astronomical. You’ll find a first edition of Sir Thomas More’s Utopia, a book of French translations in the hand of Queen Elizabeth I, a presentation copy of the only two poems of John Donne printed in his lifetime, and manuscripts of Jane Austen and Mary Shelley — the latter her Frankenstein, with corrections by her poet husband.

Religious texts are naturally prominent, since they comprised the major category both of fine medieval manuscript works and early printed books. The earliest of these is an eighth-century edition of the Rule of St. Benedict, remarkable for the imposing size and boldness of its characters. There’s the 1476 Kennicott Old Testament, a splendid Qur'an from Safavid Persia, and a 1583 Geneva Bible — the version Shakespeare would have read. A treasure of astronomical literature is the 12th-century edition of Al-Sufi’s Book of the Constellations of the Fixed Stars, and there’s a 1486 printing of Ptolemy’s Geographia, possibly the one Columbus consulted on his mistaken quest for the Indies six years later. Knowledge is, after all, the fruitful succession of errors.

The digital age, supposedly, will render the book technologically obsolete. I’m sure that will give us all more space for entertainment systems and fitness equipment. Me, I’ll stick with my book clutter. After all, the mind’s untidy, too. Or will that be the next thing to go?

What, When, Where

Marks of Genius: Treasures from the Bodleian Library. Through September 28, 2014 at the Morgan Library, Madison Ave. and 36th St., New York. 212-685-0008 or www.themorgan.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Robert Zaller

Robert Zaller