Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

I’m a Neanderthal, you’re a Neanderthal

Reconsidering the Neanderthals

Like everyone else, I read Jean M. Auel’s Pleistocene blockbuster Earth's Children series, including The Clan of the Cave Bear, in the 1980s. Though the books were silly, I credit them with beginning my fascination with Neanderthals. How exciting to imagine another race of sentient hominins, interacting with humans. I was always skeptical of Auel’s depiction of Neanderthals, though. After all, they do have bigger brains than we do. Were they really that unevolved?

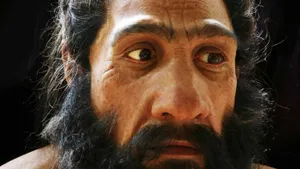

Since The Clan of the Cave Bear’s nonverbal primitives, much of what we know about Neanderthals has changed. Yes, they looked different from us: wide, protruding noses; huge eyes; and no bony chin. Foreheads were swept back and brow ridges prominent, and on the back of their heads, an occipital bun bulged. The average Neanderthal was about 5′6″, with short forearms and lower legs, which are adaptations for cold. A Neanderthal man could bench press 500 pounds, and the women about 350. Both genders hunted.

But they were more similar to us than alien. Unlike the sign language-using Clan, Neanderthals could speak, and almost surely did. Their bodies weren’t hair-covered, and many of them had blonde or red hair, light eyes, and freckles. Evidence suggests they decorated their bodies with paint, shells, and the feathers of raptors. They buried their dead. And they did all this in brutally cold Central Asia and Europe while killing mammoths with only handheld spears.

Overall, Neanderthals weren’t as strange or ugly as pop culture depictions. Many current scientifically accurate artistic renderings, with a shave and a haircut, wouldn’t seem horribly out of place walking down the street today.

Simple culture, complex tools

Neanderthals weren’t stupid either. It’s true that compared to Homo sapiens sapiens, their culture was static, showing little innovation over the 200,000 years before their disappearance about 40,000 years ago. But that’s not surprising, considering that it was the rare Neanderthal who lived past 30. Their stone flake tools were complex, using techniques taught from generation to generation. In addition, they invented the first known industrial process, production of a birch-bark glue that helped fasten stone tips to spears.

Evidence of their sophistication makes their disappearance even more tragic. Until recently, it was speculated that humans were responsible for Neanderthals extinction. The history of interactions among human cultures is filled with aggression and warfare, and the established scientific belief was that Neanderthals died off shortly after the arrival of Cro-Magnons. The sad but inescapable conclusion was that, competing with Neanderthals for scarce resources in a challenging Ice Age world, we destroyed them.

Though many aspects of her novels have since been proven factually inaccurate, Auel got one thing right — humans and Neanderthals did mate together and have offspring. Fossils had been found with features intermediate between human and Neanderthal skeletons, but those were dismissed as being like mules or ligers, hybrids that couldn’t reproduce.

Not so fast

That assertion, along with the belief that we exterminated Neanderthals, was blown out of the water by researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany. In 2010, they successfully sequenced the Neanderthal genome and found that humans and Neanderthals were 99.7 percent genetically similar to us (compared to 98.8 percent human-chimpanzee similarity). Most stunningly, humans of non-African origin carry 1 to 4 percent Neanderthal DNA.

That assertion, along with the belief that we exterminated Neanderthals, was blown out of the water by researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany. In 2010, they successfully sequenced the Neanderthal genome and found that humans and Neanderthals were 99.7 percent genetically similar to us (compared to 98.8 percent human-chimpanzee similarity). Most stunningly, humans of non-African origin carry 1 to 4 percent Neanderthal DNA.

This changes everything. Before, it was easy to believe that humanity did to Neanderthals what dominant cultures often do to primitive peoples, which is the dark side of human nature. But there’s another aspect to our nature, no less rapacious, but perhaps less sinister.

We’re the Borg of the primate world. We assimilate, not just knowledge, but whole societies.

One of the most fundamental differences between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals is neurological development. Neanderthal brains focused on visual processing and control over their larger bodies. Lacking the ability to manage large groups and complex relationships, their groups were only the size of an extended family and were geographically scattered. It’s thought that their global population wasn’t ever higher than 15,000, and they didn’t travel far from home. As a result, they were prone to inbreeding.

Humans, on the other hand, have genes that wire our brains so we can form and maintain large, dynamic social groups. As a result, humans could specialize. Men hunted, while women and children gathered. People cooperated and lived longer. When human migrations came out of Africa, they outnumbered Neanderthals ten to one. This social facility allowed us to develop what the Neanderthals largely could not, due to hardship and short lives: culture.

When Cro Magnons entered Neanderthal territory, Neanderthals were already suffering setbacks. Climate fluctuations affected their prey species, and a Neanderthal male needed about 5,000 calories a day, twice as many as the average human male. Their inability to make technological leaps made adaption difficult.

Humans do it, Neanderthals do it ...

So what did our intrepid ancestors do when we crested a hill and saw our cousins, strong in body but weak in numbers, lonely, huddling in caves? We moved in next to them and had babies. They live within our DNA, their genes carried from the Levant to the furthest corners of Europe, to Asia, and later, to the Americas. Over time, we diluted them, incorporated them, until they were indistinguishable from us. We consumed them in a very real sense, though not completely. In some ways, we also are them.

If your mind isn’t already blown by this, consider that recently, a hominin toe bone was found in Denisova Cave in Siberia. People of Oceania carry 4 to 6 percent of that hominin’s DNA, along with the 1 to 4 percent from Neanderthals. A fourth, unknown hominin is also in the mix, possibly Homo erectus, but no viable DNA of that hominin has been collected to confirm that identification.

I find this news heartening and uplifting. We didn’t just ruthlessly kill off other hominins. We also made them part of the family. I’m not so naïve as to imagine assimilation is completely peaceable or voluntary, and the exact process for the blending is unknown. But it happened, likely often, and it’s certainly superior to extinction.

Humans are patchwork beings, a hybrid species. We not only preserve our forebears’ genetic identity, but also stories about them, their families, and their daily lives. It’s what we do, what makes us special.

In fact, I’m doing it right now. I can’t help it. It’s human nature.

Above right: Germany’s Neanderthal Museum (http://www.neanderthal.de/en/) imagines a “Stone Age Clooney.” (Photo © Neanderthal Museum/H. Neumann)

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.