Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Art on the horizon

Prison, hospital, burger joint, cathedral: does art transcend the space it’s in?

In West Philadelphia, at the corner of 38th and Ludlow Streets, on the perimeter of Penn Campus, is the Philadelphia Episcopal Cathedral. From the outside, it appears as any other large urban church—steepled and red brick, snug between the corner of Ludlow Street and an attached large modern office building. But I was surprised on entering. The cathedral’s interior expanse leaves urban spatial constraints at the door. The pews have been removed, leaving chairs that can be taken away or used. The walls have traditional-looking church niches but are empty, ready to host rotating art exhibitions. The space feels expanded in all directions.

Alternative galleries

The question of space has always absorbed me. Perhaps my family’s frequent moves during my childhood—requiring so many transformations of place—made me question who I am. Is there a core-me or am I the sum of place and people? While teaching a prison art class, I quoted some forgotten philosopher, maybe misquoting, stating that we are the sum of everyone we've ever met and every place we’ve been. In response, one of my students asks, “If I’m the sum of everyone, why ain’t them all here in prison with me?!”

We can ask the same spatial identity question about art: does space transform art or is there an essential core enabling art to transcend venue? It’s what I wondered years ago when I first started looking at alternative places to exhibit my art. Would my art be the same if I exhibited in an art gallery as opposed to, say, McDonald’s? I concluded that no art could compete with the quarter pounder. Instead, I explored various medical settings, donating a number of pieces to the Flaum Eye Institute in Rochester.

Somehow, I determined prison was the best alternative place to show my work. After a circuitous route to prison, I donated 50 large paintings to a New England men’s prison. The paintings set off an angry controversy among the guards, who argued that inmates did not deserve art and prison was art-inappropriate. A few years later, the guards asked for more art, and 12 years later, the art remains.

A celestial space

More recently, however, I wondered about religious venues. Does art take on another dimension when shown in a space that has been commonly declared sacred? I posed the question to two venerable, nationally recognized Philly artists who have shown at the Philadelphia Episcopal Cathedral Gallery: James Brantley and Anne Minich.

Brantley suggested that he is basically agnostic, so as an exhibiting artist, he does not find the same meaning in the cathedral as a worshipper would. Instead, it was the architecture itself that gave meaning to him: “It’s a beautiful room with a vaulted ceiling.” Unlike the typical white walls of galleries, stripped to basics for exhibiting art, the cathedral not only invites the viewer to look at its architecture, the space demands the viewer’s attention. As Brantley puts it, “the cathedral demands a certain presence in the viewer”—a space that both transcends you and places you squarely in it. With such command, how then does art work here?

The celestial aspect of the vaulted cathedral ceiling complements Brantley’s sky paintings, which he calls his Celestial series. Many religions purport creation stories dividing heaven from hell (or other specific variations). Likewise, Brantley’s beginning point in painting is creating the horizon dividing earth from sky because “everyone needs a horizon to lean on.”

That resonates with me. One of the disconcerting things I discovered while teaching in prison, where distant vision is denied, was the lack of a horizon. When I asked people there where it was, they didn’t know. And yet, as Brantley suggests, we subconsciously lean on that line throughout the day—a sunrise, sunset, or just that border off in the corner of the eye—for both physical and emotional orientation. In the cathedral space, it is interesting to note how the realms of sky and earth (the cathedral’s celestial vault and the floor for the congregation) are connected by the skyline of art on the surrounding walls, offering that expansive experience we seek in any horizon.

No such thing as non-space

Minich offers another perspective of the horizon. Like Brantley, she finds the cathedral’s architecture more important than its purpose: “I was taken by the bays [of the interior walls] and saw each as framing for the work. The fact of it being a ‘sacred space’ isn't relevant for me. ... Personally, I regard it as an alternative gallery space.”

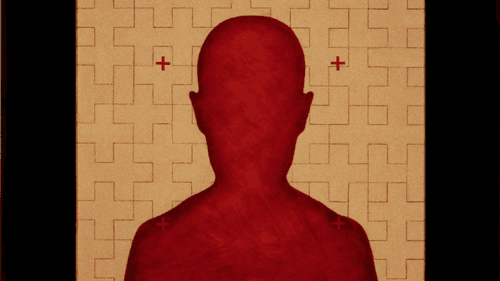

Brantley divides earth from sky, but in Minich’s silhouette portraits, the figure’s verticality gives spatial dimension. As all artists know, it is the vertical line/shape intersecting the horizon that creates the living world. In the case of Minich’s vertical silhouette portraits, the horizon line is not evident. It is the before-or-behind/facing-forward-or-backward ambiguities of the figure creating space. The layers of space are obvious, but where or how the figure is posited in those layers is ambiguous, leading to a sense of collapsed space. However, as Kant tells us, space is never gone. We can never imagine non-space. Instead, we experience ambiguous space in relationship to determined space; ambiguity is always in relationship to what is known.

A bridge across the abyss?

Is ambiguity a means of experiencing an otherness we can never know? Is art a bridge reaching across the abyss, giving us a glimpse of something we’ll never understand? Is this transcendent (for lack of another word) experience gained through art and architecture specific to place? To the cathedral? Or to other places considered sacred by common agreement or individual personal designation? Would that transcendence be shattered if the same art was surrounded by fries, burgers, and Happy Meals?

Art is always a relationship to artist, viewer, and space. Sometimes we question that relationship. Surprised to learn the paintings in the prison were mine, one student in my art class said, “I always wondered how the hell these paintings got to be hung in this prison. Here, in the bleakest place in the world!” Hearing this, I could only hope (but never ask whether) the art enables a space beyond bleakness—a hard task when the architecture of prison works to eliminate space, destroying ambiguity and mystery along the way.

However, in a sacred place of any designation, art has the potential to run parallel to the mysteries and nuances central to such places, augmenting an experience where space is always expanded.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Treacy Ziegler

Treacy Ziegler