Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

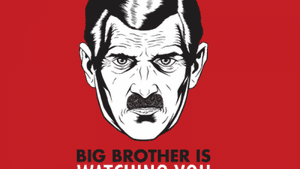

Orwell was right after all

Is privacy a thing of the past?

The principle that a man’s home is his castle was once taken for granted, although sometimes more honored in the breach than in the observance for the lesser orders. It was legally enshrined in the Fourth Amendment’s protection against unreasonable search and seizure, which meant that a man’s home couldn’t be entered against his consent without a proper warrant, nor could his personal papers or other property be subjected to inspection or confiscation.

The right to think, read and write in private was also allied with the rights of expression in speech, religion or public assembly. Freedom was indistinguishable from— and inconceivable without— privacy.

The zone of privacy was extended to a woman’s person in the Supreme Court’s landmark 1973 Roe v. Wade decision, in which privacy rights were held to trump all others, including, for those who dissented from it, the notional right of a fetus to life itself. Whether that decision was rightly or wrongly arrived at remains a matter of intense controversy. What is indisputable, however, is that it was a very direct finding for a right to privacy in the Constitution itself.

Watching me bathe

The year 1973 now seems not merely 40 but 4,000 years away. Eleven years after Roe, we crossed the mythical Rubicon of 1984, George Orwell’s year of the future in which a Big Brother state had extinguished the idea of liberty by means of eliminating privacy. The telescreen that watches Winston Smith, Orwell’s protagonist of 1984, was the prototype of the surveillance cameras that now silently monitor our movements and activities in public places. If they haven’t yet entered the home, that’s because far more efficient means of data collection have superseded them.

The state has not, as yet, taken an interest in watching me take a bath. But it silently collects, and at will peruses, the products of my mind; it can read my thoughts, especially if I’m expressing them through an electronic medium (as I am doing at this moment), almost as I think them.

That’s the world we now live in. Freedom hasn’t yet ceased to exist, but the possibility of extinguishing it has become an eminently feasible option. It’s only a short step to becoming an irresistible temptation for those who wield the powers of the modern surveillance state.

Nixon’s enemies list

We would likely have arrived at this state of affairs one way or another, given humans’ Faustian obsession with power and technology. But the tipping point, at least for the U.S., came with 9/11.

At that moment, every citizen became a potential terrorist in the eyes of the state.

It was not new, of course, for the state to regard its citizens— shall we still use that old-fashioned term?— as objects of permanent suspicion. In years past, political dissidents, real or imaginary, were “anarchists” or “subversives.” The difference, as we entered the 21st Century, was that the state’s power to monitor the citizen body was exponentially increased.

The era of Richard Nixon’s enemies list now seems positively quaint. We are all on that list now; it is the U.S. census itself.

Confession booths

Technologically, the portal that opened us all to inspection was the Internet. Ironically, this was the innovation once hailed as a new birth of freedom, giving everyone virtually instant access to everyone else and thereby vastly increasing the powers of communication and organization that constitute the basis of public life. Privacy was an afterthought, but the giant servers that carried the new electronic traffic promised users that their transactions would be confidential, except of course to commercial exploiters.

It shouldn’t surprise anyone that this promise wasn’t kept, and that Google, Yahoo, AT&T and the rest soon became direct feeders into the national security pipeline. As we now learn, some of them have been paid for this service, but they had little choice but to provide it, and if some of them are now assuming the posture of outraged civil libertarians, it’s because their foreign business is being adversely affected.

It wasn’t only the possibility of external surveillance that threatened privacy, however, but also the giddy rush to abandon it by a public already tutored in the notion of self-exposure by, among other things, TV reality shows. Previously, sins had been confessed in church. Now, with Facebook and YouTube, people could divulge the most intimate details of their lives to an unlimited audience. It soon seemed that the state’s ever-increasing powers of observation were matched by many people’s desire to reveal as much of themselves as possible.

Obama as Big Brother

In the new surveillance world, the right of privacy remains only for Big Brother, whose name is currently Barack. Nothing, of course, is as securitized as President Obama’s personal work and living space. When he travels, he takes a special tent whose sides are opaque and which is equipped with noise-making devices that distract outside attention, including the sensors that otherwise monitor him as well. In this portably hermetic bubble the president can function as a master of the universe, wielding the powers of life and death.

In 1984, no space remains for freedom, and Winston Smith, the novel's degraded subject, can only dimly intuit what he’s missing and what he loses forever when his spirit is finally crushed. Our Winston Smith is Edward J. Snowden, an intelligence drone who seems to have gradually awakened to the moral implications of his service and has cried aloud his warning to us all. But instead of receiving gratitude and honor for this courageous act, Snowden was hounded to the ends of the Earth and finally obliged to seek asylum— in one of the profounder ironies of our time— from the former head of Russia’s secret police.

Nor was it only the executive branch that pursued Snowden with such single-minded rage. When John Dean, Nixon’s counsel, testified before Congress about the so-called White House horrors in 1974, the Senate granted him immunity. The present Congress has vastly more to learn from Snowden. He is willing to testify. No one, however, seems interested in hearing from him.

Congress, too, has apparently been vacuumed into the surveillance state. Rest in peace, Frank Church.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Robert Zaller

Robert Zaller