Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

They were fourth graders.

Children on the edge: a fourth-grade poetry teacher mourns Uvalde

They were fourth graders. Nine years old, maybe 10. Old enough to write poems; young enough to occasionally fall out of their chairs. Some—not many—wore masks: plain black ones or flowered ones or the softly pleated, sky-blue surgical ones we’ve all grown used to, muffling each other’s faces.

I’m not talking about those fourth graders, the ones you’ve been reading about since last week, when a teenager slipped into a school in Uvalde, Texas, and opened fire with a legally purchased AR-15, turning an ordinary Tuesday into one more national trauma.

I’m thinking of a different group of children, the ones I taught this spring in an elementary school in Princeton. Children who—on the same morning when that Texas teen sprayed more than a hundred bullets, also legally purchased, into two fourth-grade rooms—were slurping from water bottles and counting the minutes until lunch.

On the edge

I teach poetry to children of all ages, but fourth grade is my sweet spot. The bruising self-consciousness of puberty hasn’t quite set in. Their imaginations flare: peacocks of extravagance, lightning zags of truth. They’re goofy (fart jokes are still a hoot in fourth grade) and profound, vulnerable, and unapologetically weird. They hover on the ripe edge between kid and adolescent; sometimes, if you look closely, you get a glimpse of the toddler they were or the adult they’re going to become.

That is, the adult they will become unless a man too young to buy a beer drives to their school one morning, shouldering a lethal firearm he purchased the day after he turned 18.

“Ask any question”

With the other fourth graders—not the ones who phoned 911 in whispers, not the one who smeared herself with a classmate’s blood and played dead in case the gunman came back—I shared part of Pablo Neruda’s The Book of Questions as a writing prompt. “Ask any question,” I said. “Anything you have ever wondered about life or death, the future or the past, nature or human behavior.”

They wrote.

Who are the sun’s parents? What if plants told you how hard they work to break that tough shell? Does water ever want to take a break and stop flowing? Is everything a chair? What would it feel like not to exist?

A horrible day

When my own daughter was the age of those fourth graders, her class adapted Judith Viorst’s picture book Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day into a play.

In Viorst’s book, Alexander goes to sleep with gum in his mouth and wakes up with gum in his hair. His brothers find prizes in their breakfast cereal, but all Alexander finds is breakfast cereal. The hours muddle on—cavities at the dentist, lima beans for dinner. Alexander drops his sweater in the sink. He bites his tongue.

The book is meant to be a relatable litany—mundane calamities that now seem, in light of Uvalde and Parkland and Sandy Hook and too many other places, to be a kind of privilege, a giant stroke of luck. Imagine that: a “horrible day” that doesn’t mean your classroom became a killing field.

"Viorst believes it's harder to be a kid today," notes an NPR story about Alexander's 50th anniversary this week. "I think the world has gotten tough and even if they're not watching the news and reading these incredibly depressing stories, I think it must seep into them," she says.

At one point in the story, an exasperated Alexander declares, “I think I’ll move to Australia.”

In Australia, a 1996 massacre prompted the government to launch mandatory gun buybacks; the rate of mass shootings dropped from one every 18 months to one—that’s right, just one—in the 26 years since. Citizens widely accepted the buyback and supported the gun limitations; some even gave up weapons they were legally allowed to keep.

Just the facts

Fourth grade is typically the year when a health teacher, or maybe the school nurse, gathers kids into groups for an introduction to the “facts of life.”

How about these facts?

- A Politico poll released last week showed that 88 percent of voters strongly or somewhat support background checks on all gun sales.

- There have been 228 mass shootings so far this year in the United States, according to the Gun Violence Archive. Seventeen of those happened in the week after the Uvalde killings: West Philadelphia. Anniston, Alabama. Chattanooga. Chicago. Port Richmond.

- The Gun Violence Archive defines a mass shooting as an incident in which four or more people are shot or killed, excluding the shooter.

More? Here’s some of what we know about the gunman in Uvalde. He’d been bullied for a speech impediment. Some of his co-workers at Wendy’s called him “school shooter” because of his penchant for dark clothes and long hair. When a classmate rebuffed his invitation to go out, he used Instagram to send her messages like “I hate you” and “I’m going to hurt you.” He made aggressive, sexual comments to young women on social media.

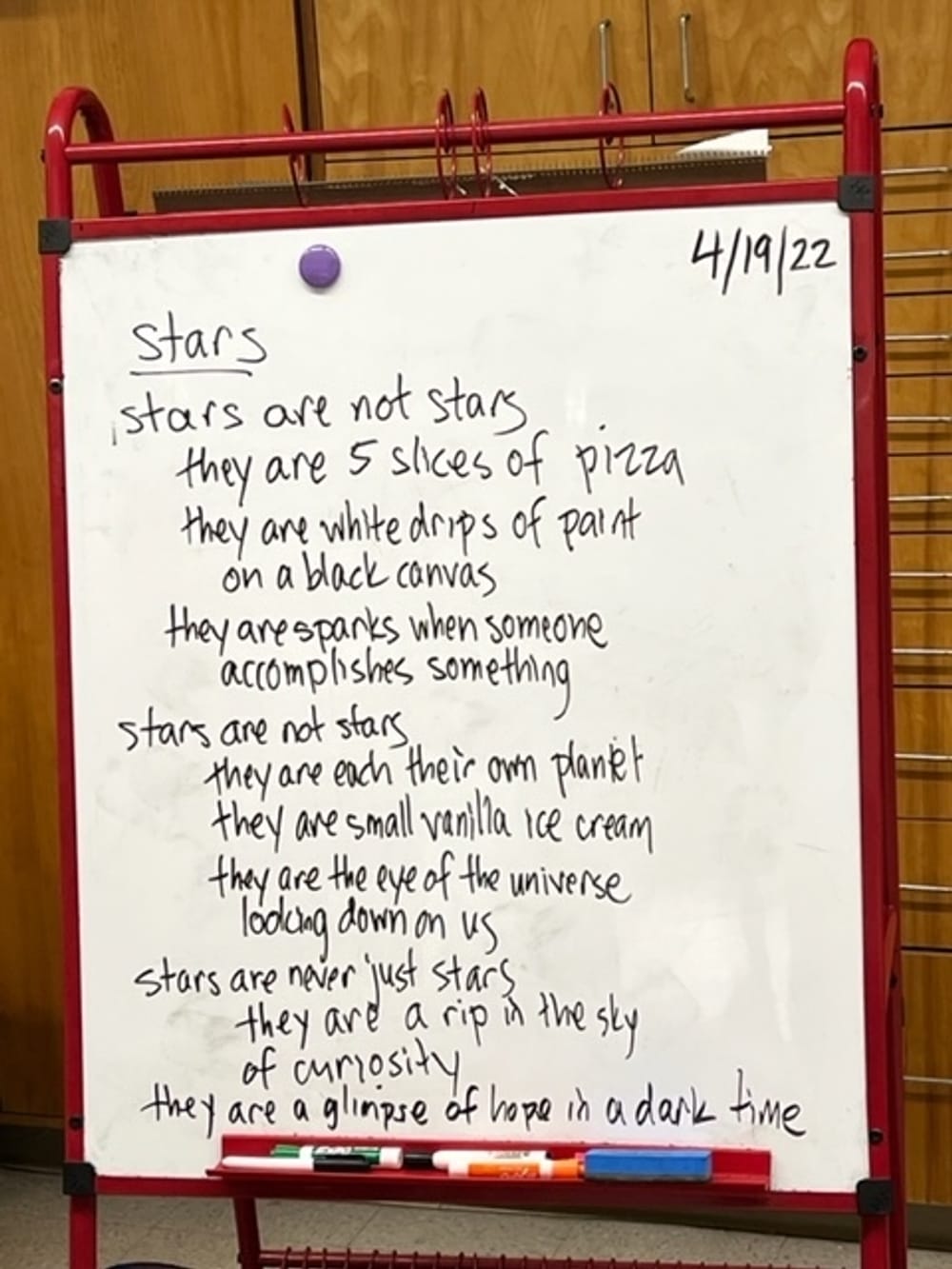

On a different day of my week with the fourth graders—the other ones, the ones who are still alive—they wrote personification poems; the idea was to inhabit a particular emotion, imagining how that feeling would move, what it would eat, how it became … well, whatever it is. One student wrote: “Anger has a bad history. His parents left him. Someone was mean.”

The ordinary thing

The day her class was scheduled to perform Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day, my daughter, who was playing Alexander, woke with sniffles and a low-grade fever. She begged to go to school. We let her.

Maybe that was a little irresponsible, but it was just a cold, and she’d only be there for a couple of hours. As a parent, you’re always making judgment calls like this, juggling risk and opportunity and desire, crossing your fingers, hoping it will turn out okay. For your kid. For all kids.

The show went on, with a makeshift curtain on a cord across Ms. Becky’s classroom and a small audience of parents with jobs flexible enough to dash to school in the middle of the day. My kid wore overalls with a backwards baseball cap and gamely scowled through Alexander’s lines.

And when it was over, after the curtain call and the juice boxes and the high-fives all around, we did the ordinary thing, the reflexive thing, the only thing any parent ever wants to do at the end of the day. We hugged our kid and took her home.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Anndee Hochman

Anndee Hochman