Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Between a march and a hard place

Attending the Women’s March in Philadelphia — or not

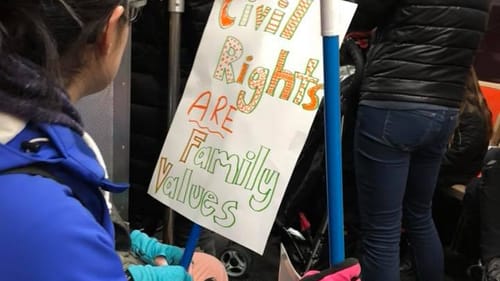

Homemade posters and rousing chants will abound on January 19, 2019, as people take to the streets for two (yes, two) marches on Philadelphia. Chants like “Show me what democracy looks like/This is what democracy looks like” will thunder out of the mouths of participants, but one announcement threatens to drown out the rest.

“I’m not anti-Semite. I’m anti-termite.” For me, a Jewish woman, it is an utterance that refuses to be muffled, and for other Philadelphia Jews it is loud enough to keep them from marching altogether.

Troubled roots

The Women’s March national organization and its protests have struggled with intersectionality and inclusion since the beginning. But 2018 saw Women’s March leaders Linda Sarsour and Tamika Mallory facing heightened scrutiny for their ties to Louis Farrakhan and his hate speech against Jewish people.

Mallory, in particular, is under fire for her unapologetic attendance at Farrakhan’s February 2018 event in Chicago, where he declared that “the powerful Jews are my enemy” and that Jewish people are “satanic.” He would later double down on the rhetoric at a speech in October and liken Jewish people to termites in the tweet quoted above. While Mallory and Sarsour have made statements disavowing anti-Semitism, neither of them is paving the way for a hard break from Farrakhan — also known for his misogynistic and anti-LGBTQ comments.

Criticism of Mallory and Sarsour also comes from inside the organization. Teresa Shook, one of the co-founders of the Women’s March, called for Sarsour and Mallory, as well as co-leaders Carmen Perez and Bob Bland, to step down in a public Facebook statement last November, stating that “they have allowed anti-Semitism, anti-LBGTQIA sentiment and hateful, racist rhetoric to become a part of a platform by their refusal to separate themselves from groups that espouse racist, hateful beliefs.”

What would Philly do?

The internal fracturing is splintering outward. Numerous state chapters, including Illinois, Florida, and Alabama, are breaking away from the national organization to form their own syndicates. New Orleans, Chicago, and Northern California have canceled their marches to distance themselves from the mother organization and to stand firmly against anti-Semitism.

With the aftershocks of the Pittsburgh synagogue shooting still rippling through the state and anti-Semitic acts across the country continuing to rise, what should Pennsylvanians do?

It’s harder to ignore the significance of the national Women’s March leadership’s watery nonapologies when fears of further terrorist acts against Jewish people are high. I know several Philadelphia Jews in my own network who have chosen to abstain from marching, citing a lack of proactive action against anti-Semitism as cause for concern.

“Do I think the current leaders of the Women’s March are anti-Semitic?” asks Polly Edelstein, artistic director of the Philadelphia Women’s Theatre Festival. “I don’t know, but they certainly haven’t done enough to prove that they aren’t, which means they’ve become relatively ineffectual in representing all women.”

Philly Women Rally

The Philly march under the umbrella of the national Women’s March organization is scheduled to proceed. According to its website, it’s gathering at 10am in Love Park. And what about the other march spearheaded by Philly Women Rally (PWR)? It’s also scheduled to start at 10am, from 1700 Benjamin Franklin Parkway, and march to Eakins Oval for a rally featuring local speakers, running 11am to 2pm.

PWR is its own entity, proudly independent from the national Women’s March and explicitly denouncing anti-Semitism in all its forms. But it’s not immune to problems. In December, an Inquirer article cited soap-opera-level conflict among the organizers, including accusations of stolen funds and the ousting of founder Emily Cooper Morse.

The tumult, scandal, and infighting of both organizations is troubling. Between the drama of one and the insufficient action of the other to counteract the alienation of Jewish people, it’s not appealing to throw myself behind either march. I’m finding it difficult to compartmentalize, to overlook the failings of the organizations and lend my presence to activism that feels tainted. And I can’t get Farrakhan’s hateful epithet out of my mind. I don’t like that this man, with a powerful position in our national consciousness, can deny my humanity — especially when I feel powerless to stop him.

Showing up

This conundrum isn’t new. The Farrakhans of the world aren’t new, either. But there are those who acknowledge this detriment and continue fighting the fight every day. Other minority groups (religious and otherwise) face similar or worse vitriol, yet they show up. In the beginning stages of the Women’s March, when it was largely a platform for white feminists sporting pink pussy hats, people of color and LGBTQ+ folx marched alongside them — even if it meant setting aside their own pain.

There’s a HuffPost article I frequently turn to that details American Jews’ obligation to resist white supremacy in the age of Trump, thereby honoring our own history of oppression. In it, Julia Sharpe-Levine writes, “The Jewish American community is not a monolith; on the contrary, it contains as many diverse identities as America itself, and therefore its freedom can never be disentangled from the freedom of every other marginalized group.”

Jewish people cannot ignore the plight of other minorities, because our identities are intertwined. Jewish people cannot stop marching, because we don’t just march for ourselves. We also march in support of others, in support of a larger goal that supersedes whataboutism.

Beyond marching

That being said, the Women’s March isn’t the zenith of political action. Too many engage in "tourist activism," making the Women’s March their good deed for the year and then absenting themselves from other efforts, like Black Lives Matter protests. And marches, by definition, are a kind of activism that excludes many people with disabilities. Fortunately, there’s no shortage of options if you don’t want to march or are unable to — like letter-writing, calls and emails to your representatives, volunteering for grassroots campaigns, and donating to causes, to name a few.

Whatever you decide, do something. Do whatever is in your conscience and your power. When the words and deeds of unstable and unreliable leaders jeopardize the future of our democracy, action becomes the currency of we the people.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Alix Rosenfeld

Alix Rosenfeld