Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

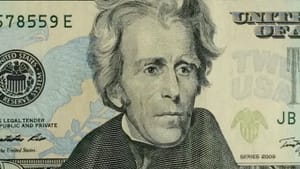

On giving Old Hickory the business

In defense of Andrew Jackson

Will nobody speak up for Andrew Jackson?

America’s seventh president has graced the $20 bill since 1928, but now a rising revisionist chorus is demanding Old Hickory’s replacement by a Native American or an African-American or a woman — anyone but (as Gail Collins put it in the New York Times) a “slave-owner who came to national renown as an Indian-killer.”

In the past month alone, Jackson has been savaged twice on the Times op-ed page. Steve Inskeep, cohost of NPR’s Morning Edition, noted that before he was president, Jackson the soldier expanded America’s borders by brutally driving the Creek Indians out of Alabama and driving the Spanish out of Florida. (Click here.) An Internet campaign called “Women on 20s” recently conducted a poll to find a woman to replace Jackson. The winner was Harriet Tubman, the escaped slave who returned to the South repeatedly to lead other slaves to freedom. Gail Collins, applauding this choice, also reminded her readers that Jackson, as president, “made hatred of the national bank his big issue, while showing a certain fondness for state banks owned by his cronies.”

Collins might have added that Jackson didn’t lift a finger for Catholics, Jews, Hispanics, or the LGBT community. Nothing like judging a 19th-century figure by 21st-century standards.

Combative demeanor

Yet in the context of his own era, Andrew Jackson was a transformational figure. At the very time that the right to vote was being extended from gentlemen of property to all taxpaying white adult males, Jackson’s humble roots and his indomitable energy spoke to Americans as a harbinger of the egalitarian future, unlike the elite Virginia and Massachusetts patricians who had occupied the Executive Mansion before him.

“His awful will stood alone, and was made the will of all he commanded,” Jackson’s friend, Supreme Court Justice John Catron, remarked of him after Jackson’s death in 1845. “If he had fallen from the clouds into a city on fire, he would have been at the head of the extinguishing host in an hour. . . .Those who never worked before, who had hardly courage to cry, would have rushed to the execution.”

In effect, Jackson’s combative demeanor emboldened ordinary Americans to assert themselves as citizens instead of subjects deferring to an elite leadership caste. This was the essence of Jacksonian democracy, which has driven American dynamism ever since: the notion that ordinary private citizens possess the power to change their world.

Jackson’s movement represented an inspiring but also bitterly divisive force among Americans in his day, rallying West against East, new against old, and the “producing” classes (farmers and laborers) against the “non-producing” business community that controlled banks, education, the press, and government. But long after those issues were forgotten — long after Jackson himself was largely forgotten — that sense of empowerment-from-below drove the reforms that subsequently liberated slaves, workers, women, and other minorities to this day.

Rabbi of Chelm

Jackson was a flawed human being, no question. He owned slaves — although, to judge from his slaves’ tears at his funeral, he was a relatively benevolent master. He fought Indians tenaciously — but at the time, Jackson was a soldier and Indian tribes were technically considered hostile foreign nations. He helped to drive the Spanish out of Florida — which may be the best thing that ever happened to Florida. It’s also true that President Jackson was clueless about how banks work — but then, as I have discovered during my long career as a financial journalist, so are most other people, including many business reporters and even some bankers themselves.

I yield to no one in my admiration for Harriet Tubman, a remarkable woman whose courage demonstrated the extent to which a single determined individual, even of the most humble birth, can make a difference in her society. And it’s surely not a bad idea to rotate America’s national heroes on our coins and paper money periodically. But those who disparage Andrew Jackson today remind me of the Yiddish folk tale abut the rabbi of Chelm, who concluded that the moon is more important than the sun because “the moon shines at night and gives us light with which to see, whereas the sun shines during the day, when there is no need for it whatsoever.” Jackson constituted such a powerful sun that it’s all too easy to take him for granted.

For Judy Weightman's response to this essay, click here.

For Tom Purdom's consideration of the related issue of whether presidents should be on U.S. currency at all, click here.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Dan Rottenberg

Dan Rottenberg