Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

He did it his way

Andrew Greeley, latter-day Erasmus

"I used to be in the dove camp," my rabbi, Avi Winokur of Society Hill Synagogue, has been known to remark. "Now I'm in the hawk camp."

The polemicist Norman Podhoretz, similarly, jumped in the 1960s from the radical leftist camp to the extreme conservative camp. The world is full of philosophers and opinion shapers who, having seen the light, have jumped from one camp to another.

If camp-jumping works for these folks, who am I to stop them? Certainly politicians, soldiers, athletes and evangelists would never see much playing time if they declined to commit themselves to one particular team. (Imagine Billy Graham: "And so I say to you that the day of judgment is probably coming. Or maybe not. Who really knows?")

But why would anyone who deals in ideas feel the need to align himself to any particular camp?

For security, you say, or companionship. It's much easier to speak up when you have an "amen corner" of like-minded supporters behind you.

Maybe so, but still: What do security, companionship and a loyal claque have to do with the search for truth?

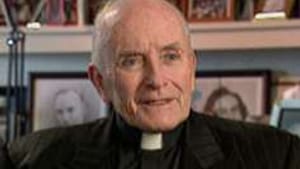

Attacking the bishops

These reflections are prompted by the death last week, at age 85, of the Reverend Andrew Greeley, a combative priest, scholar, social critic, novelist and outspoken public scold who steadfastly refused to identify himself with any institution or philosophy and insisted instead on maintaining an open mind on every issue he encountered.

Greeley was an ordained Catholic priest who thought of the priesthood as his core identity. Yet he once described America's Roman Catholic bishops as "morally, intellectually and religiously bankrupt." As early as 1989 he began writing articles in Chicago newspapers demanding that the Church take action against pedophile priests. He documented the human costs of the Church's resistance to birth control.

On the other hand, Greeley ardently defended parochial schools, priestly celibacy and traditional Catholic piety against attacks by secular intellectuals and reform-minded Catholics. Against the widespread intellectual assumption that religion was a fading force in the world, he argued that religion is "the result of two incurable diseases from which humankind suffers: life, from which we die, and hope, which hints that there might be more meaning to life than a termination in death." The trouble with religion, he insisted, was that it had ossified from poetic images and inspiring stories into creeds and catechisms concerned above all with the exercise of power.

Steamy sex novels

Because of his independent state of mind, Greeley was never granted a parish of his own. How, then, did he survive and flourish without institutional support?

In his younger days Greeley did rely on institutions for a living. He taught at the University of Chicago and worked at the National Opinion Research Center in Chicago, which surveys American attitudes about religious and cultural issues.

Bu the real source of his independence was his writing. Greeley wrote more than 120 books, as well as op-ed pieces and syndicated columns in scholarly journals and popular magazines alike.

More to the point, he also wrote steamy best-selling novels, many of them rife with Vatican intrigue, wayward priests and illicit sex. The novels made him rich. They also developed a loyal constituency. Instead of relying on the Church to deliver him a parish, he created his own much larger de facto parish out of his hundreds of thousands of loyal readers. He derived his authority not from any institution but from the power of his words.

Erasmus: Distant mirror

In many respects Greeley was the walking reincarnation of the Renaissance Dutch humanist Erasmus of Rotterdam. Like Greeley, Erasmus (1466-1536) was an ordained Catholic priest who refused to check his brains at the Church door and asserted his right to reach his own conclusions on any topic. Also like Greeley, he was a teacher, theologian and social critic who derived his independence from the power of his words.

His humanistic writings and his outspoken criticism of Church abuses helped pave the way for the Protestant Reformation, but Erasmus also rejected Martin Luther's belief in predestination and grace through faith alone. Because Erasmus refused to endorse either Catholicism or Protestantism and insisted instead on finding a middle way between them, he made enemies in both camps.

Those enemies are largely forgotten today. Erasmus, like Greeley, understood his priorities.♦

To read responses, click here.

The polemicist Norman Podhoretz, similarly, jumped in the 1960s from the radical leftist camp to the extreme conservative camp. The world is full of philosophers and opinion shapers who, having seen the light, have jumped from one camp to another.

If camp-jumping works for these folks, who am I to stop them? Certainly politicians, soldiers, athletes and evangelists would never see much playing time if they declined to commit themselves to one particular team. (Imagine Billy Graham: "And so I say to you that the day of judgment is probably coming. Or maybe not. Who really knows?")

But why would anyone who deals in ideas feel the need to align himself to any particular camp?

For security, you say, or companionship. It's much easier to speak up when you have an "amen corner" of like-minded supporters behind you.

Maybe so, but still: What do security, companionship and a loyal claque have to do with the search for truth?

Attacking the bishops

These reflections are prompted by the death last week, at age 85, of the Reverend Andrew Greeley, a combative priest, scholar, social critic, novelist and outspoken public scold who steadfastly refused to identify himself with any institution or philosophy and insisted instead on maintaining an open mind on every issue he encountered.

Greeley was an ordained Catholic priest who thought of the priesthood as his core identity. Yet he once described America's Roman Catholic bishops as "morally, intellectually and religiously bankrupt." As early as 1989 he began writing articles in Chicago newspapers demanding that the Church take action against pedophile priests. He documented the human costs of the Church's resistance to birth control.

On the other hand, Greeley ardently defended parochial schools, priestly celibacy and traditional Catholic piety against attacks by secular intellectuals and reform-minded Catholics. Against the widespread intellectual assumption that religion was a fading force in the world, he argued that religion is "the result of two incurable diseases from which humankind suffers: life, from which we die, and hope, which hints that there might be more meaning to life than a termination in death." The trouble with religion, he insisted, was that it had ossified from poetic images and inspiring stories into creeds and catechisms concerned above all with the exercise of power.

Steamy sex novels

Because of his independent state of mind, Greeley was never granted a parish of his own. How, then, did he survive and flourish without institutional support?

In his younger days Greeley did rely on institutions for a living. He taught at the University of Chicago and worked at the National Opinion Research Center in Chicago, which surveys American attitudes about religious and cultural issues.

Bu the real source of his independence was his writing. Greeley wrote more than 120 books, as well as op-ed pieces and syndicated columns in scholarly journals and popular magazines alike.

More to the point, he also wrote steamy best-selling novels, many of them rife with Vatican intrigue, wayward priests and illicit sex. The novels made him rich. They also developed a loyal constituency. Instead of relying on the Church to deliver him a parish, he created his own much larger de facto parish out of his hundreds of thousands of loyal readers. He derived his authority not from any institution but from the power of his words.

Erasmus: Distant mirror

In many respects Greeley was the walking reincarnation of the Renaissance Dutch humanist Erasmus of Rotterdam. Like Greeley, Erasmus (1466-1536) was an ordained Catholic priest who refused to check his brains at the Church door and asserted his right to reach his own conclusions on any topic. Also like Greeley, he was a teacher, theologian and social critic who derived his independence from the power of his words.

His humanistic writings and his outspoken criticism of Church abuses helped pave the way for the Protestant Reformation, but Erasmus also rejected Martin Luther's belief in predestination and grace through faith alone. Because Erasmus refused to endorse either Catholicism or Protestantism and insisted instead on finding a middle way between them, he made enemies in both camps.

Those enemies are largely forgotten today. Erasmus, like Greeley, understood his priorities.♦

To read responses, click here.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Dan Rottenberg

Dan Rottenberg