Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Context never rests

Visitor feedback leads a long-planned makeover at the Delaware Art Museum

Plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose. This French axiom posits that “the more things change, the more they stay the same.” But as the Delaware Art Museum reinstalls its collection, shifting the entire first floor of the acclaimed regional museum, its curators are finding that the more things might seem to stay the same, the more they are actually changing.

Once created, most pieces of art might remain static, but their meaning is absolutely not. And along with the shifts in interpretation due to societal and cultural changes, the physicality of moving artworks is always a challenge, even if they are staying in the same building. Each time even one artwork is relocated, the curators, preparators (who handle the art), and registrars (responsible for catalogue details), as well as education and marketing staff, have myriad details to shift, since each work newly hung on a new wall changes the context of everything around it.

Just imagine, then, the challenge of moving 300 pieces of art, as well as changing entirely both their display and interpretation. At the Delaware Art Museum, it took three years of intensive strategy and thoughtful planning to model and choreograph these changes. Staff had planned to begin, gallery by gallery, to reconfigure and reimagine their displays on March 30 of this year. Of course, we all know how impossible that turned out to be.

Pandemic benefit

As museum staff return for the reopening, the reinstallation plans can finally be put in motion. But as chief curator Heather Campbell Coyle notes, rather than being an additional burden, the pandemic hiatus—and the societal changes unfolding around it—have actually been beneficial to the project in several ways.

For example, it has given curators time to refine their messages. Of course, there are always new acquisitions, and once in the collection, museum objects don’t change, but their interpretation does. Views that were topical, accepted, or even groundbreaking 20 years ago (the last time the museum did a major shift like this) need to be rethought. To foreground new narratives and refocus how viewers will experience the artworks, the museum (led by its education and community engagement staff) employed a process called prototyping.

Prototyping change

Prototyping is somewhat unusual in the art world; it’s a technique more commonly used in science museums. For more than two years, museum visitors were asked to respond to individual artworks by writing their impressions, questions, or suggestions on large sheets of paper or Post-it notes next to works of art. In effect, staff was asking what information viewers might like to know that didn’t appear on the existing wall labels.

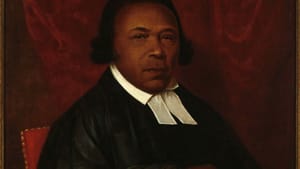

Coyle says that the prototyping campaign “asked a lot of the staff, but we also learned a lot.” Begun long before current (and overdue) calls for diversity and inclusion, this process led museum staff to instigate some major interpretive changes. For instance, the number and strength of viewer queries and thoughts about Raphaelle Peale’s 1810 portrait of a prominent Philadelphian, African American abolitionist and clergyman Absalom Jones, proved that the painting is of great interest to visitors. Prototyping feedback will result in the work’s reinstallation as the focal and entry point of the American galleries.

In the British Pre-Raphaelite collection, curator Margaretta Frederick used viewer comments to foreground information about the relevance and roles of that 19th-century movement’s prominent women. Long portrayed mostly as muses and models, many of these women were also accomplished artists, writers, and advocates for social change. The reinstallation will more completely “unpack their contributions and illuminate who they really are.”

Another museum strength is its holdings of the artworks and archives of early 20th-century American “Ashcan” artist John Sloan. Viewer interest—and the fact that the museum has become a destination for Sloan scholars and visitors—prompted Coyle (a respected Sloan scholar) to move his galleries to the museum’s main floor, with plans to “make his artistic rebellion clearer.”

Commitment to dialogue

Prototyping is a demanding and evolving process, something possible here (according to highly lauded Philadelphia-area exhibition designer Keith Ragone) by this museum’s scale and commitment to dialogue. For Ragone, reflecting a community is critical to his work, and he found it “rare to be in a design process with a team so deeply committed” to this process.

Coyle says that Ragone’s reinstallation design also includes plans for spaces with the flexibility to tell a variety of stories, and staff have worked to find “real estate” that can allow for responses to topical issues. And another change—engendered solely by coronavirus considerations—is a museum-wide shift from guided group tours (previously the norm for visitors in most institutions) to newly created individual audio tours.

Such a large reconfiguration plan means changes in almost every museum area, and so galleries will be closed on a clearly indicated rotating basis. Staff will work to minimize off-view time, something especially important for collections like the Pre-Raphaelites or Sloan that are “visitor destinations.” This means that the entire process, which was originally to have taken place from March over the summertime, will actually encompass almost a full year.

But Coyle is confident that the result will be new spaces engaging a broader public by bringing each viewer into a more personal dialogue with the museum’s art, telling more clearly the stories—old and new—that can illuminate our time and this place.

What, When, Where

Delaware Art Museum, 2301 Kentmere Parkway, Wilmington, DE. (302) 571-9590 or delart.org

The Delaware Art Museum reopened to members on July 1 and to the general public on July 15. Visitor numbers are monitored, and everyone is required to wear a face mask to enter. Here’s the full list of COVID-19 safety tips for visitors.

Museum facilities, entrances, galleries, and parking are accessible, and wheelchairs are available to borrow at no cost.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Gail Obenreder

Gail Obenreder