Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

How we were… and still are

The Free Library presents ‘Philadelphia: The Changing City’

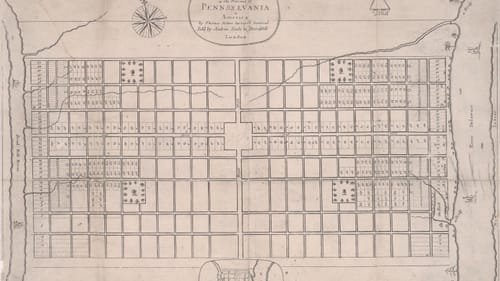

Seeing Philadelphia: The Changing City is like climbing into the family attic, without the scent of mothballs. Maps and prints culled from Free Library of Philadelphia (FLP) collections document the city from 1683, when it was nothing more than a grid on paper. Though decidedly low-tech, the exhibit, presented in the Rare Book Department, will delight anyone who appreciates Philadelphiana.

From caves to row homes

According to Eliza Leslie’s historical Game of Philadelphia (1831), “Many of the first settlers of Philadelphia were obliged to live in caves till they were able to erect better habituation.” According to the card game, the last inhabited caves were at Townsend’s Court, near Second and Spruce.

Frank H. Taylor’s idea of better habituation, created for the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago, would become the archetypical Philadelphia residence. For the Philadelphia Chamber of Commerce, he sketched The City of Philadelphia [in the year 1900], a prototype brick rowhome with pavement-level basement windows, marble front steps, and a decorative cornice that’s still instantly recognizable.

Redlining’s roots

Housing is a recurrent theme in The Changing City. How houses look, how much they cost, where they’re built, and who lives where are issues that have ignited arguments here forever—inflaming conflicts rooted in ethnicity, social class, and political clout. An egregious example is “redlining”—shorthand for racial discrimination in home selling and mortgage financing, and the J.M. Brewer Survey of Philadelphia (1934) reveals the origin of the term.

Drawn by C.R. Rosenberger from demographic data Brewer compiled, the map was developed as an analytical tool for real estate investment. Demographic statistics on neighborhoods’ racial composition, income, age of housing stock, and property values were depicted graphically on a city map. Green indicated Italian areas, blue denoted Jewish areas, and red where residents were, in 85-year-old parlance, "Colored."

Exhibit signage indicates that the Brewer map wasn’t created with malign intent, yet it became a model for maps that were used to deny equal opportunity in housing and lending. The legacy of redlining, which continued legally for decades, created injustices that still plague Philadelphia.

A few words from our sponsor

Period advertising makes the past resonate in ways history books may not. It’s one thing to read that “Philadelphia was a center of textile manufacturing,” and quite another to see Philadelphia in 1886 (Burk and McFetridge), a five-by-six-foot wall map depicting the city in its oft-mentioned “Workshop of the World” phase. It’s edged in announcements for textile businesses like Amber Dye Works, which tinted carpet yarn and fine wool; Nye & Tredick, maker of circular ribbed knitting machines for hosiery and sweaters; the Falls of Schuylkill Carpet Mills, offering “all grades of carpeting, many of them far below market prices”; and Edward Ridgeway, fabricator of curtains and upholstery.

Similarly, the accordion-fold brochure Panorama of Philadelphia (1864, E. Rogers) offers a view into the closets of well-dressed men. Unfolded, it measures four feet, and is a masterpiece of engraving. The brochure, made for the Great Central Fair on Logan Square, a Civil War fundraiser, features a river-to-river engraving of the skyline studded with landmarks—some long-gone, like the House of Refuge, and others still extant, such as the Academy of Music.

Below the skyline, advertisements tout numerous clothiers, including “Gents Furnishing Goods” dealer C. Henry Love, who sold gauntlets, half-hose, night caps, dressing gowns, smoking caps, money belts, over-gaiters, and “shirts and collars made to order and warranted to fit.” Nearby is an ad for Wanamaker & Brown, forerunner of the still-fondly-remembered John Wanamaker department store.

How we got here

Moving through a city that sometimes seems held together with temporary barricades and detour signs, you might conclude that Philadelphia just sort of oozed into existence. But no: Several items in The Changing City reveal the extensive planning that went into, for example, establishing a single public transportation system (Department of City Transit map, 1914) or locating high-speed roads (Philadelphia’s First Expressway, 1949 Philadelphia City Planning Commission pamphlet).

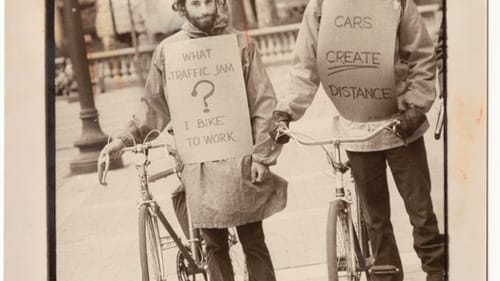

The exhibit is also a reminder that Philadelphia has long had an avid biking community, and that the relationship between bicyclists and nonbicyclists has always been testy. Artifacts include an 1897 cycling map and a 1977 photo of a pro-bicycle protest in Rittenhouse Square.

What we lost and saved

Philadelphia has frequently allowed short-term considerations to override historic preservation, a point illustrated by materials tracing the contrasting fates of the Boyd theater and a Philadelphia Fire Department (PFD) pumping station.

Photographs and documents recall the heyday and subsequent decline of the Boyd at 19th and Chestnut. The historic movie theater, which itself had replaced the Aldine Hotel, was the focus of a pitched preservation battle until 2015. Ultimately, most of the structure was demolished to accommodate residential development.

The PFD station on Delaware Avenue met a happier fate. The only surviving structure from a 1924 waterfront view, the station was built to improve water pressure for firefighting and was decommissioned as technology eclipsed its usefulness. Rather than being demolished, though, it was repurposed in 2013 as home to FringeArts, which promotes and presents contemporary performance art.

The Changing City is enjoyable for anyone. Though it requires time to fully appreciate, the range of topics and periods are so varied that whether viewers are recent arrivals in Philadelphia or lifers, they’ll find lots to intrigue and inform.

What, When, Where

Philadelphia: The Changing City. Through April 13, 2019, at the Free Library of Philadelphia’s Parkway Central Branch, 1901 Vine Street, Philadelphia. (215)-686-5416 or freelibrary.org/rarebooks.

The Parkway Central Branch of the Free Library is an ADA-compliant building.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.