Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Wyeth’s double life

The Brandywine River Museum presents ‘N.C. Wyeth: New Perspectives’

The Brandywine River Museum has opened N.C. Wyeth: New Perspectives, the first major reconsideration of Wyeth in almost 50 years. This comprehensive exhibition affords a fresh and cogent look at the work of an early 20th-century artistic giant who was a celebrated American illustrator, visual storyteller, and muralist. Wyeth illustrated 112 books and made myriad narrative paintings, but throughout his prolific commercial career he kept seeking new artistic perspectives, so the exhibition title carries a double resonance.

Over two floors, Wyeth works from major museums and private collections are elegantly displayed in a chronology that at first seems straightforward. But the exhibition gathers emotional power as Wyeth’s beloved and familiar illustrations are juxtaposed with “personal” canvases that become increasingly reflective and experimental in form, content, or materials.

Illustration versus art

Illustration—once separated from the world of “fine art” and considered lesser—has now moved into the mainstream. But that was not so in the early 20th century, when the young art student Newell Convers Wyeth (1882-1945) moved to the Brandywine Valley from Needham, Massachusetts, to become a student of the great illustrator and teacher Howard Pyle.

Though his studies in Massachusetts at first followed a traditional art curriculum, Wyeth had a gift for narrative painting that quickly propelled him into the ranks of the foremost illustrators. While still Pyle’s student, he presented himself at Philadelphia’s Curtis Publishing with his 1903 painting Bucking Bronco (he learned about horses not from travel but from the Needham polo grounds) and immediately secured the coveted commission of a Saturday Evening Post cover.

From his early illustrations, Wyeth became known as an artist of the American West, until he was hired by Scribner’s in 1911 to illustrate Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island, creating in a meteoric rise the pictures still vivid today.

“This terrible rut I’m in”

New Perspectives is a trove of these great illustrations, displayed in the order they were painted and published. Even though we’ve seen them over many years and in many places, these large (Wyeth mostly painted big) works are still forceful and engaging. But the exhibition’s deeper message is subtly but tellingly explored by curators Christine Podmaniczky (of the Brandywine Museum) and Jessica May (Portland Museum of Art, where the exhibition will appear in October). They contend—and show—that throughout his career, while Wyeth was lionized for illustration, he was consistently, creatively, and longingly exploring the parallel world of fine art.

It’s enormously striking to see an illustration like The Last of the Mohicans next to an impressionistic work like Buttonwood Farm, both done in 1919. Over the 70 works on view, these convincing juxtapositions appear again and again. As Wyeth’s commercial career kept expanding, he called illustration “this terrible rut I’m in” and continued to make works like The Dusty Bottle (1924), a still life so vivid you want to wipe off the painting’s varnished black surface.

Maine and the Brandywine

Wyeth’s artistic longings, deep and broad, were satisfied geographically in two places still important to the family: the Brandywine Valley and Port Clyde, Maine. He compared the Brandywine region, with its “big sad trees,” to “soft and liquid music.”

Much has been made of the realism of this locale in his most famous illustrations, but it’s even clearer and more plangent in the paintings that he did purely for himself. The energy of Wyeth’s early illustrations never truly disappears, but you can feel a marked shift in later works as the emotional pull away from commercial storytelling and into the world of interpretation intensified.

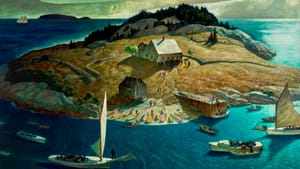

Some personal works profoundly illustrate Wyeth’s artistic explorations. Bright and Fair (1936) is a light-filled work that speaks like an Edward Hopper canvas. The beautiful and expansive bird's-eye-view Island Funeral (1939) marries his penchant for narrative (here mysterious) with modern tendencies, including the use of new DuPont colorfast dyes in its green and blue glazes. And Night Fall (1945), his last painting in the exhibition, is a work of pure longing, depicting a reflective man gazing outward but clearly experiencing an unspecific visceral sense of inner regret.

Deep dive into Wyeth

Because of the museum’s immersion in the work of the Wyeth family, as well as the exhibition’s chronological design, the curators have made a cogent case for the dichotomy between the bread-and-butter work and the seduction of easel painting that Wyeth struggled with all his life.

A helpful film at the exhibition’s entrance—with terrific footage of Wyeth at work and at play—effectively frames this curatorial premise. But it is the artist himself who makes the case most movingly. “I want to paint a picture with nothing but a soul,” he says, a striving clearly seen on the Brandywine Museum walls. Even for those endowed with, grounded in, and impassioned by great gifts—as N.C. Wyeth indubitably was—success has perils as well as heights, something this artist knew about all too well.

What, When, Where

N.C. Wyeth: New Perspectives. Through September 15, 2019, at the Brandywine River Museum of Art, 1 Hoffman’s Mill Road, Chadds Ford, PA. (610) 388-2700 or brandywine.org/museum.

The Brandywine River Museum is an ADA-compliant venue. Find more info on accessibility here.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Gail Obenreder

Gail Obenreder