Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Beyond Kahlo and Rivera

Philadelphia Museum of Art's Paint the Revolution: Mexican Modernism, 1910-1950

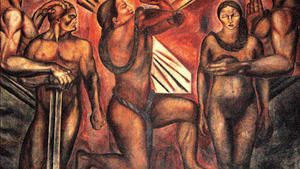

Art as a political statement is nothing new. The Pharaohs didn’t build the Pyramids of Giza just to pay homage to their dead. The same goes for the paintings and sculptures commissioned by the Vatican to remind Europe’s monarchs who was really in charge. But it is the art of Mexico in the first half of the 20th century, as presented in the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s new exhibition, Paint the Revolution: Mexican Modernism, 1910-1950, that takes the concept to an entirely new level.

When Mexican artists embraced the battle cries of Emiliano Zapata and Pancho Villa, who championed the poor against the elites, they also appropriated the rich cultural heritage of Mexico’s indigenous peoples. Until then, Mexico had mostly looked toward Europe for its cultural influences. Suddenly, it looked to its pre-Columbian past. Artists started depicting the nobility of the farmer, housemaid and peasant.

Turning back, synthesizing the present

This rediscovery of the past gave rise not just to a uniquely Mexican approach to art, but it also reintroduced and elevated Mexican culture in North America and Europe. Upper class Frida Kahlo garbed herself in the embroidered clothing and jewelry of rural Mexican women, a statement that quickly spread across the United States, along with a new fervor for Mexican pottery and ceramics.

While the usual suspects, Kahlo and Diego Rivera, are well represented, the works of other Mexican artists are the most compelling, perhaps because they aren’t as well known here. For instance, David Alfaro Siqueiros’s large-scale pastel, Peasants (1913), hints at influences of Van Gogh in both color and line. José Clemente Orazco’s mixed media The House of Tears (1916) depicts a brothel with crude images reminiscent of Viennese artist Egon Schiele.

If I had to pick one painting that represents the movement’s rediscovery of its native peoples, it would be Roberto Montenegro’s Mayan Women (1926). The painting shows incredibly powerful profiles of four indigenous women, posed as if to say, “We were here before you arrived. This is our land. You cannot suppress us any longer.”

Politics in paint

All of these images gain their strength from the influence of pre-Columbian art, which adds volume, mass, and simplicity to the European influences of cubism, impressionism and abstraction. Many Mexican artists studied in Paris, including Rivera, whose Eiffel Tower (1914) employs Cubism.

Besides the glorification of the humble peasant, the exhibition doesn’t flinch from depicting the murderous violence of the Mexican Revolution. Nothing could be more lurid than José Clemente Orozco’s Combat (1925), or The Rape (1926).

The brutality of these images brings to mind equally horrific images of our own time: Police shootings, bombings, terrorism, to say nothing of the calls to incitement in our current presidential election. Are there U.S. artists energized by these subjects? Diane Burko comes to mind for her oversized paintings of the endangered environment. But I cannot think of any U.S. artists who dared to satirize their affluent Wall Street patrons by showing them as bloated figures of conspicuous consumption and buffoonery as Rivera did so expertly in his mural The Orgy (1926).

Europe and the U.S. make appearances

Rivera didn’t just look to his Mexican heritage in conceiving of these monumental murals. He spent time studying Michelangelo’s and Giotto’s Italian frescoes. What you see in this exhibition is the ways Mexican artists incorporated their unique cultural imagery into a European artistic heritage. If you are wondering how the museum manages to display Rivera’s spectacular murals, they achieve it via floor-to-ceiling video projection, an ingenious solution.

Standouts include Siqueiros’s defiant Zapata (1931), Carlos Mérida’s blank-eyed Self-Portrait (1935) and Alfredo Ramos Martínez’s Zapatistes (1932). Frida Kahlo lovers will find plenty to admire, including the seldom seen The Suicide of Dorothy Hale (1936), an altarpiece in memory of Kahlo’s friend, aspiring U.S. actress Dorothy Hale. One of the piece’s distinct features is its frame, painted to extend the image. Also of interest is a lithograph of a young Kahlo by Rivera, in which she is entirely nude except for stockings and high heels. It conveys both innocence and eroticism.

I was mesmerized by an entire gallery that was dedicated to political posters, newspaper illustrations, and prints, all created as propaganda for labor unions and political organizations. The images are strong and include illustrations condemning the Nazi genocide underway in Europe.

What, When, Where

Paint the Revolution: Mexican Modernism, 1910-1950. Through January 8, 2017 at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2600 Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia. (215) 763-8100 or philamuseum.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Stacia Friedman

Stacia Friedman