Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

More than meets the eye

Philadelphia Museum of Art presents 'Experiments in Motion: Photographs from the Collection'

Experiments in Motion: Photographs from the Collection at the Philadelphia Museum of Art revisits the wonder of pre-digital photography, when artists subject to bulky equipment, finicky film, and darkroom development pushed the medium to unveil sights beyond the capacity of the human eye. With a flash of light, an unblinking shutter, and instant film, they froze fluid motion and showed what happens between here and there.

As pictures pour down from the cloud, it’s easy to forget how miraculous photographs used to be. An image can stop time, preserve memory, and eclipse the laws of physics and mortality. Photographs make the past present and the invisible visible.

Bodies in motion

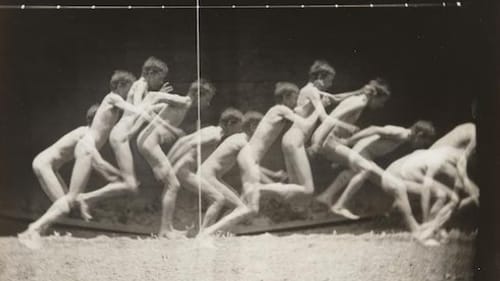

Painter Thomas Eakins was also a gifted photographer. He appreciated both the artistic and technical uses of photography, using it for his own practice and to teach his students at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. He employed it as an extension of anatomical drawing, to figure out how bodies move in space.

In Motion Study — Boy Jumping to the Right (1884), Eakins recorded a young long-jumper. Discrete images progress across the frame, forming two arcs of spindly appendages, pointy knees, hips, and elbows folding and unfolding as the boy twice propels himself through the air and lands. The scientific dissection evokes a visceral response, as onlookers’ muscles tense with the memory of their own youthful leaps.

More than a century after Eakins, Zoe Strauss photographed another jumper in South Philly (Mattress Flip Front) (2001). A young African-American boy enters the frame from the top, headfirst. Suspended in mid-somersault, his only security is a stack of ragged mattresses piled beneath him in the street.

He’s backed by a painted brick wall that’s seen better days, and a friend, hand held to mouth in amusement. Strauss freezes a moment that would otherwise be forgotten, stilling the fearless boy so we can examine his surroundings, marvel at the stunt, and wonder what became of him.

Trial and error was the secret to Eliot Porter’s Blue-Throated Hummingbird (Male) (1941). Kodachrome was notoriously touchy, needing long exposure and tending to fade — not at all suited to photographing a hummingbird in flight.

Undaunted, Porter synchronized a strobe light to his camera. With painstaking persistence, he finally produced a split-second color image of the tiny bird, wings flapping deliriously.

Happy accidents

A broken advance mechanism wound an entire roll of film past Barbara Blondeau’s open shutter, exposing every frame. Another shooter might have become agitated and grudgingly fixed the equipment. Blondeau was transfixed by the serendipity the snafu produced.

The exposed length of film revealed subjects moving through space and time, a stop-action cinéma vérité. She continued to make the “strip pictures,” as she called them, including Untitled (1971), an abstract black-on-white strand of up-down slashes that look like an orderly herd of zebras ambling by.

When photographs were made on film, waiting for images to emerge from trays of developing and fixing chemicals could be stressful. Beginning in the 1940s, Polaroid relieved photographers’ agony with the invention of self-developing film — first sepia, then black and white and, by the 1960s, color.

Visible images now took only a minute or so, and while most photographers carefully guarded the magical squares as results came into view, some preferred to play with the still-forming images. In Photo Transformation, September 19, 1976 (1976), Lucas Samaras dragged a stylus back and forth through his self-portrait. He wound up looking like a neon-pink lightning bolt.

Expressing emotion

Having the ability to stop motion photographically benefits scientific investigation, but it also expands photographers’ creative palette, a point made clear by David Lebe, who like Blondeau, treated his open shutter like a canvas.

In the darkness of his Philadelphia apartment, Lebe drew with a flashlight in front of the camera, switching it on and off to inscribe glowing images. By 1987, Lebe, now in a studio, undertook a series of flashlight works in response to his despair over a friend dying of AIDS.

Lebe saw the beam of light as life ebbing from his friend, and works such as Scribble #23 (1987) express the artist’s desperation and loss in an illuminated bouquet of curling tendrils, reaching upward.

What, When, Where

Experiments in Motion: Photographs from the Collection. Through August 19, 2018, at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2600 Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia. (215) 235-7469 or philamuseum.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.