Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Terrorism, then and now

Haverford College presents ‘The Legacy of Lynching: Confronting Racial Terror in America’

“From the tree to the electric chair.” This videotaped statement from Anthony Ray Hinton, who spent 30 years on death row for a murder he didn’t commit, is one way to sum up The Legacy of Lynching: Confronting Racial Terror in America, an exhibition running at Haverford College’s Cantor Fitzgerald Galley through December 16.

More than 4,000 lynchings took place in 12 Southern states between 1877 and 1950, and this exhibit doesn’t treat lynching as a barbaric but dead piece of America’s history. Instead, it’s part of a continuum extending into Jim Crow injustice, voter suppression, and other historic and contemporary evils that give rise to today’s Black Lives Matter movement.

The past lives

It’s an embodiment, perhaps, of William Faulkner’s observation that “the past isn’t dead. It’s not even past.” This Haverford event originated with a show at the Brooklyn Museum of Art, which in turn had ties to the nonprofit Equal Justice Initiative’s National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Alabama.

The Equal Justice Initiative is “committed to ending mass incarceration and excessive punishment in the United States, to challenging racial and economic injustice, and to protecting basic human rights for the most vulnerable people in American society.”

The closest this exhibit comes to actually depicting a lynching is Ken Gonzales-Day’s photo of one, with the victim blacked out. Only the white spectators are visible.

Lindsay V. Reckson, an assistant professor of English at Haverford and an organizer of the exhibit, says this was deliberate. The designers of the original Brooklyn exhibition did not want the ghastly nature of lynching pictures to distract from the overall message.

Confronting history

The small but incredibly powerful show is grouped into two categories of work.

One is a series of six videos, in which victims of unequal justice or descendants of victims of racial terror tell their stories. They speak of life in regions where people would lynch a black man for writing a note to a white woman and where planned lynchings could get advance newspaper stories, attracting crowds numbering in the thousands, with the governor of Mississippi saying he was powerless to intervene.

Here we learn that the “Great Migration” of black Southerners to the North in the early 20th century was not solely made up of those seeking economic opportunities. Some were simply staying one step ahead of the sheriff or the lynch mob — which were virtually interchangeable in some cases.

The great-great-granddaughter of lynching victim Anthony Crawford, of Abbeville, South Carolina, tells his story through archival photos and documents. There’s a powerful contemporary coda: a memorial plaque at the scene of his lynching.

“Now,” Crawford’s descendant says, “if you go to Abbeville City Hall to do business, you have to walk by Anthony Crawford. You can’t bypass him anymore.” A small counterpoint, perhaps, to the myriad Confederate monuments scattered throughout the state.

Or, in the words of descendant of a man who fled the state to save his life, “How do you get through if you don’t confront history?”

A quilt, a map, and more

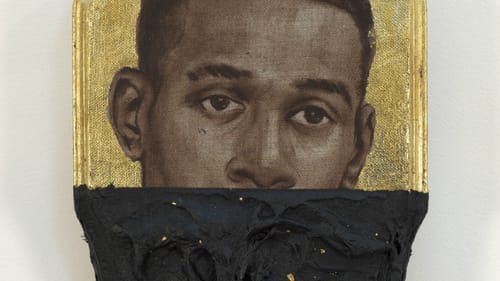

The rest of the exhibit includes works that are sometimes clearly relevant to the theme but may also have connections so tenuous that long explanations are necessary. Titus Kaphar’s Jerome XVI is a moody reflection on imprisonment and facelessness that struggles to find a place in the exhibit.

Visitors entering the gallery are greeted by an interactive map of Southern lynching locations. Josh Begley’s Officer Involved is a Google Map of killings of black people by police. Bars, by Hank Willis Thomas, is a quilt made from decommissioned prison uniforms.

“We hope it will travel to other campuses and galleries,” Reckson says of the Haverford show.

You can help keep BSR going strong in 2019 and beyond. Make your gift here.

What, When, Where

The Legacy of Lynching: Confronting Racial Terror in America. Through December 16, 2018, at Haverford College’s Cantor Fitzgerald Gallery, 370 Lancaster Avenue, Haverford, PA. (610) 896-1287 or Haverford.edu.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Paul Jablow

Paul Jablow