Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Textiles and hypertext

Drexel’s Robert and Penny Fox Historic Costume Collection dons a digital design

You know Drexel’s URBN Center, right? No? Head south on 36th Street until you hit Filbert Street—also one way, so hang a left. No? Not yet?

Even among Drexel University’s other buildings, the URBN Center is unremarkable, overshadowed by its own annex across the street. Within the garagelike edifice, however, lies a 1,200-foot gallery and an underpublicized collection associated with Drexel University: the Robert and Penny Fox Historic Costume Collection (FHCC). But the collection is more than just costumes—started in 1898, it preserves a stunning variety of contemporary fashion. The collection’s first exhibition, in 2015, was a debutante event that promised similar successes to come.

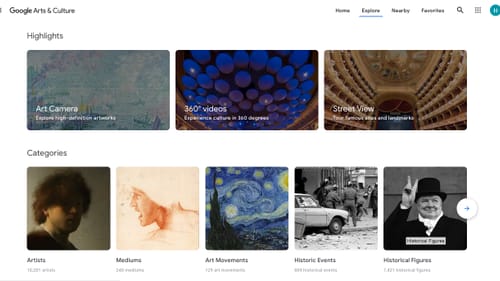

Now the FHCC has been temporarily shuttered and, as Gail Obenreder recently noted in BSR, many museums, galleries, and cultural institutions have embraced technology to connect with visitors. Sometimes this effort happens within individual institutions, and sometimes bigger players join in. These include Google Arts & Culture, among the leaders of the cultural digitization migration.

And that’s where FHCC’s story continues.

What Google noticed

FHCC has three exhibitions featured on the Google Arts & Culture platform, the crown jewel being the gallery’s debut exhibition, Immortal Beauty, whose success effectively brought the FHCC into the limelight.

“I’m pretty sure that’s how Google came to us,” curator Clare Sauro told BSR. After a Wall Street Journal review of the show, Google first approached the Philly collection in April 2016, when Google was assembling its “We Wear Culture” project, centered on fashion. “This was invitation only,” Sauro said. “So we wound up being only one of, I think, five university costume collections invited to participate, and we’re one of only three in the United States … At that time, we didn’t even have a gallery.”

Taking the catwalk from the curator

The original exhibition was carefully curated by Sauro, who structured the exhibition’s narrative chronologically, beginning with an 1883 mantel made by Charles Frederick Worth, founder of the Parisian couture. One glance at the Google Arts & Culture iteration, however, quickly transforms the original exhibit’s défilé presentment to prêt-à-porter, banishing curatorial oversight and giving viewers the option to select pieces to view at will from a gallery of any given museum’s holdings.

“I did have to let go of the idea that I was in control, and that’s hard,” Sauro said. In the physical Immortal Beauty exhibition, “the teal dress was next to an orange dress and a pink dress. And that was the group. They were the three muses together, and they made sense.” The pink dress, Sauro recalls, didn’t make the cut online. “I like to have the garments interact with one another, to tell a story,” she explains.

For his part, Simon Delacroix, the US lead for Google Arts & Culture, emphasized that a user’s ability to customize collections “aims to help people find new ways to engage with and explore art,” and that whether users are passionate about art or have a lighter interest, Google “wants to help people find connections within collections.”

And for Sauro, the additional opportunity for FHCC’s collections to be searched and discovered through the Google database was too great to pass up. She laughed, “I got over myself and my methods and said, ‘OK’.”

Gallery aesthetics online

But even though the Arts & Culture homepage has a dizzying array of live recordings, selfie filters, and “daily doses” of culture, and might pretend to dethrone the editorial voice of curators, there are things about the platform that still evoke that “museum” atmosphere, such as the pale echo of the White Box—an almost ubiquitous component of many museums’ visual displays, characterized by white walls and ceilings and neutral floors.

The digital architecture quietly calls upon this aesthetic. Text is often white and demurely inset into display images; headings are presented in a conversational style; and the titles between images are neutral colors, sans-serif, and slickly functional. The aesthetic evokes institutional authority and at the same time brings the FHCC’s collection and those of other museums to the visual foreground, elevates the role of the user, and implicitly deemphasizes Google’s presence while still relying on subtle elements of contemporary museum display.

Perhaps most interestingly—and most unassumingly—Google’s platform quietly distances the FHCC collection from the Drexel University banner and places the relatively small physical establishment on similar terms with institutions such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Musée d’Orsay, and the Guggenheims. “Otherwise, we’d never be able to do that,” said FHCC archivist Michael Shepherd.

The future of digitized museums

So what’s next? While both Sauro and Shepherd credit the online platform with equalizing museums and allowing smaller institutions to flaunt their holdings, each noted that the initiative may have stalled, at least for the moment.

Sauro said another FHCC exhibition on American designer James Galanos is in the pipeline, but that Google has likely been “inundated” lately, and she doesn’t know when the newer exhibit might be brought to life on the digital platform. In the meantime, curator and archivist are each enthusiastic about efforts to build an independent digital exhibition, which the FHCC was already developing before the pandemic, with hopes of unveiling in October.

“I think virtual reality and technological developments have a lot to offer creatively,” said Shepherd, who wondered with interest how online projects might take physical form once museum premises reopen.

Open to all ages

A deeper focus on interactive exhibits and a younger audience is happening online as well as in physical institutions. Delacroix emphasized youngster-oriented additions as an important update at Google Arts & Culture.

“We know many families are spending more time inside, and many parents [are] educating and entertaining their kids each day,” he said. The new Family Fun page was created with parents and caregivers in mind. Delacroix recommends exploring the Big Bang in augmented reality, checking out the illustrator who’s working on the next generation of Harry Potter tomes or tiptoeing behind a penguin loose in the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum.

“I’m not a kid anymore, but I’ll admit I still find it a lot of fun,” Delacroix said. Whether the FHCC will follow penguin suit remains to be seen.

What, When, Where

The Robert and Penny Fox Historic Costume Collection’s digital exhibitions are available through Google Arts & Culture.

The FHCC is located on the first floor of Drexel’s URBN Center (currently closed), 3501 Market St., Philadelphia. (215) 571-3504 or drexel.edu/foxcollection.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Helen Walsh

Helen Walsh