Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Lest we forget

Delaware Art Museum presents three exhibitions for "Wilmington 1968"

Fifty years ago, the National Guard occupied Wilmington, Delaware. The city was a virtual war zone, locked down for over nine months, the longest occupation of a U.S. city to date. To commemorate that time, 20 organizations have mounted the community-wide reflection Wilmington 1968. The Delaware Art Museum focused its interpretive and curatorial resources on a trio of interlocking exhibitions: a stunning photographic record by Danny Lyon, personal responses from Harvey Dinnerstein and Burton Silverman, and a newly created major commission from Hank Willis Thomas.

Danny Lyon: Memories of the Southern Civil Rights Movement

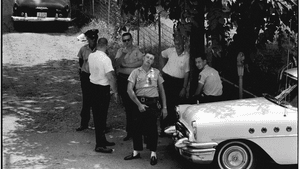

A Brooklyn Jew born in 1942, Lyon — a lion of photojournalism — still takes pictures, writes, and makes films aligned with his early call to social justice. From his first published images (on view here), Lyon worked in the style of New Journalism — immersed in his subjects, not an observer but a participant.

He admired the Civil War photographs of Matthew Brady, and in 1962 — inspired by a speech by civil rights activist and U.S. representative John Lewis — he taught himself to use a camera. He then convinced the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) to accept him as its photographer.

From that vantage point, Lyon was present at most major civil rights events. The 57 photos in this exhibition are a testament to his determination, narrative skill, and insightful eye.

Set against a 1960s palette of orange and grey walls and printed with the historic silver gelatin process, these are unvarnished images filled with the energy of a committed young man. Most are journalistic, though some cross into art photography or portraiture, black-and-white images that evidence an often arresting compositional skill.

Even as you appreciate their artistry, the subject matter jolts you to the reality of that disturbing and violent time. Whether by curatorial plan or serendipity, the works’ double impact directly links with the two visual layers of the museum’s commission (see below).

The exhibition includes a timeline of “Civil Rights Milestones,” a wall for community responses, and two blown-up posters with the SNCC headquarters location: “8½ Raymond Street NW, Atlanta 14, Georgia.” The touching specificity of that address speaks to the passion experienced and captured by Lyon.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott: Drawings by Harvey Dinnerstein and Burton Silverman

The same gallery holds a smaller exhibition of beautiful drawings. Classical in style, the works (mostly in graphite) are remarkably affecting, made by young New Yorkers Harvey Dinnerstein and Burton Silverman.

The two men read about the yearlong Montgomery, Alabama, bus boycott (sparked by Rosa Parks in December 1955), but couldn’t find images of the event. In spring 1956, they decided to document it themselves and traveled south.

Small in size but large in meaning, the 29 drawings celebrate the strength of Alabamans whose dogged courage transformed the American south. Heather Campbell Coyle curated both this and the Lyon exhibition, and it was an inspired idea to pair the New Journalism images with these intimate drawings.

Dinnerstein’s finely detailed Court Square is clearly an homage to Daumier. Boycotter, Montgomery (1956) captures a weary, overall-clad man trudging in the heat of the day, juxtaposed with a delicate European-style fountain. And his image of Rosa Parks — whose action started it all — reflects serenity itself.

Silverman’s style is looser and more active. Man on a Porch could be a sketch by Edward Hopper, and his depiction of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in court captures the man’s watchful strength.

In both artists’ drawings, the image often floats or bleeds into the white space around it; its vibrancy can’t be contained by the frame. The works on view are drawn from 1990s gifts augmented by thoughtful museum purchases, an example of how unexpectedly prescient, inspiring, and empowering major gifts can be.

How to Live Through a Police Riot — Hank Willis Thomas

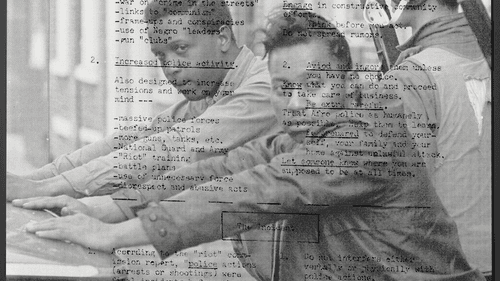

While the above exhibitions depict moments in time past, Thomas created his look back as formed, informed, and expanded by technology. Highly conceptual, commissioned by the museum and curated by Margaret Winslow, these 14 works were mined from the archives of the Delaware Historical Society to create an interactive tour de force: large-scale panels imprinted with text from an almost unbelievable 1968 handbook (hence the title) published during the National Guard lockdown.

The retroreflective screen prints carry hidden images beneath the text. When you shine a light on them — the museum provides handy lighted glasses, or you can use a cellphone — life-sized period photographs from the Wilmington News Journal spring into view.

The concept is so cool and the technology so hot and seductive that it takes a while to focus on the overwhelmingly disturbing content, and — like Lyons’s photographs — coming to terms with it is sobering. That these images are at first not visible to the naked eye speaks to the things unknown or unseen that shape us, and the work also seeks to “confront gaps in our collective histories.”

In conjunction with the exhibitions, the museum hosts community forums and performances, and its July 13 opening was packed with excited viewers. Some came because they remembered the time, some because they were participants. Some came to view the works as art, and some brought children to show them — and remind themselves — of what was and what could still be.

Amazingly, all four artists are living, and all three exhibitions present art beautifully mounted in the service of communal memory: powerful reminders, lest we forget.

What, When, Where

“Wilmington 1968” exhibitions: Danny Lyon: Memories of the Southern Civil Rights Movement and The Montgomery Bus Boycott: Drawings by Harvey Dinnerstein and Burton Silverman, both through September 9, 2018. Hank Willis Thomas Commissioned Artwork: Black Survival Guide, or How to Live Through a Police Riot, through September 30, 2018, at the Delaware Art Museum, 2301 Kentmere Parkway, Wilmington, Delaware. (866) 232-3714 or delart.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Gail Obenreder

Gail Obenreder