Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Folklore and fakelore

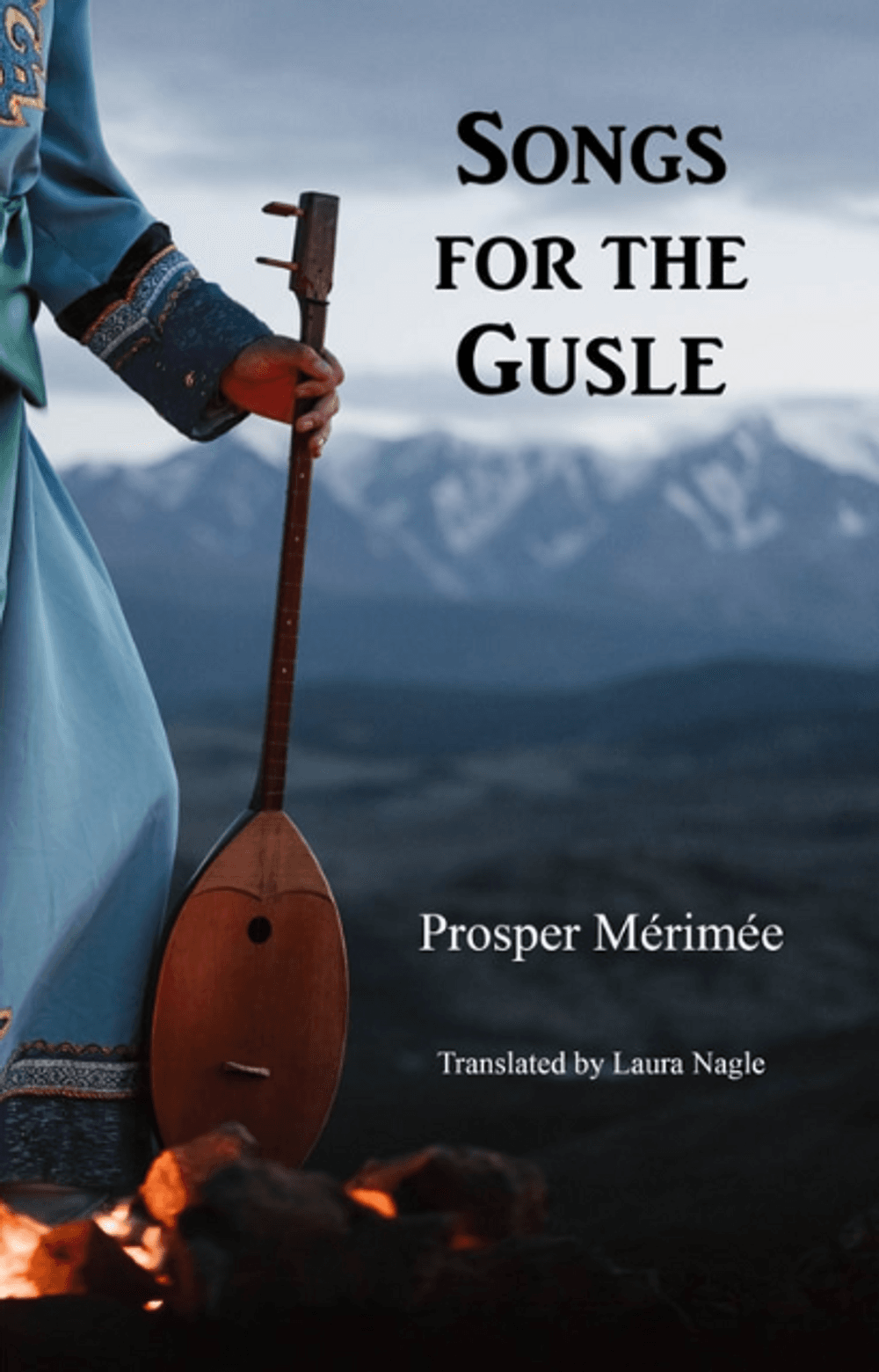

Songs for the Gusle, by Prosper Mérimée; translated by Laura Nagle

At first blush, Songs for the Gusle is exactly as it appears: a slim book of verse. Originally translated by an anonymous traveler and published in French in 1827, the book contained scraps of ballads, folklore, and poetry the translator claimed to have gathered during travels in Illyria, around the area of modern-day Croatia, Serbia, and Italy.

Published in English now, almost 200 years later, songs such as “The Feud between Lepa and Chernyegor” still burn with tragic friendships and losses, while others such as “The Vampire” and “Lover in a Bottle” paint the vivid if shadowy presence of the supernatural. Filled with natural imagery ably rendered in the English translation, the words of gusle players real or imagined evoke the pain and pleasure of the unknown, striking chords centuries later and often taking the form of a series of short stanzas.

For example, “The Morlach in Venice” recounts the story of a heartbroken man convinced to move from his home to the city. The fourth stanza: “Fool that I was, I believed him, and I came to this great vessel of stone; but the air here suffocates me, and their bread is poison to me. I cannot go where I please, cannot do as I please; I am like a dog on a leash."

Later, in the sixth stanza: “On my mountain, any time I encountered a man he would greet me with a smile, saying, ‘God be with you, son of Aleksej!’ But here [in the city] I find no friendly faces. Here I am like an ant flung by the breeze into the middle of a vast pond.”

These days, there might be fewer wandering minstrels and gusle players; no one can argue there are fewer dogs on leashes.

Or can they? Today’s Songs of the Gusle is deftly conveyed in English by translator Laura Nagle, who reanimates not only the songs but also the character of that first, anonymous translator, whose commentary and footnotes are still sprinkled like salt and pepper throughout the collection.

Well, more like salt—as the pages turn, it’s difficult to ignore a certain sniffiness in the tone of the anonymous translator’s footnotes; in the note placed on the title of “The Morlach in Venice,” the anonymous translator whines that “the presence of some outdated expressions suggests that this is a very old tune, one that precious few old men can still imbue with meaning.” Definitions are repeated. Footnotes become self-referential dead ends. Anachronous literary comparisons appear like worms on wet pavement—what is going on?

Does it seem almost too convenient for this small anonymous translator that there is, as he observes in the preface, an “ever more prevalent appetite for foreign works, and especially for those that deviate, in their very forms, from the masterpieces we generally admire?" Should we trust this anonymous translator as did Mary Shelley, Alexander Pushkin, and Johann Goethe?

This final question forms part of the puzzle that Nagle seems to delight in laying out for us in her translation. And fortunately for readers who are satisfied with resolution, both she and Prosper Mérimée pull back the curtain, smartly relocating an explanatory 1840 forward to the end of the volume “so as not to ‘spoil the fun’ of those encountering this text for the first time,” according to Nagle.

The “fun” of textual analysis is open to debate. Fortunately, however, Nagle renders the ache of ballads and folktales just as skillfully as she does the pointy-nosed parsimony of her alleged predecessor. Both help Songs for the Gusle sing.

What, When, Where

Songs for the Gusle. By Prosper Mérimée; translated by Laura Nagle. Philadelphia: Frayed Edge Press, March 21, 2023. 141 pages, softcover; $20. Get it here.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Helen Walsh

Helen Walsh