Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Will art museums speak to us in the future?

Winterthur Museum welcomes National Gallery of Art director Kaywin Feldman

What’s the difference between, say, a theater and a museum? Performing arts need a venue—but when a production or concert ends, the audience leaves, the set is struck, and the artists head home. Not so for most museums—what’s on their frontier? In a November appearance at Winterthur, museum director and dynamo Kaywin Feldman, a leading thinker about inclusive arts futures, showed why museums offering art to the public must seek new audiences and better ways to serve them in “a radically new time.”

Performing arts presenters, including theater, music, and dance, must maintain or find venues. They have some physical constraints, but their “inventory” is basically ever-changing as they present limited runs of a changing roster of works. Visual arts can likewise intersect with the public in temporary ways: artists and galleries put changing “wares” before audiences, and some museums are non-collecting institutions. These care for what’s on view, but the art doesn’t live there.

Art lives here

However, in the US, the preponderance of visual art presented to the public comes via museums, whose expansive buildings house and display myriad objects that must have controlled temperature, humidity, light, and security.

I’ve worked in both performing and visual arts institutions. And when I took my first bona fide museum job, I was stunned to realize the voracious demands of the ever-present, ever-demanding maw of the physical plant. Displaying, caring for, housing, and securing objects is a 24-hour, year-round task. Doors may close, but museum systems must be perpetually maintained, and the staff is ever on call.

This constant physical need is coupled with the acquisitive drive by institutions and donors to collect more art—that’s why museums were founded. And all these concrete factors are now in play against the dynamism of wildly changing trends and demographics.

Nine trends from a trailblazer

In March 2019, Kaywin Feldman shattered a glass ceiling, becoming the first woman director of the National Gallery of Art. Until her arrival, this artistic behemoth on the National Mall (part of the Smithsonian) had a somewhat staid reputation. She came from the Minneapolis Institute of Art (which she broadened to considerable acclaim) and was a former president of the Association of American Museum Directors, a powerful professional group.

Feldman is noted for a fearless (sometimes controversial) commitment to opening up museum culture to become more inclusive. In her recent Winterthur lecture, she spoke to young professionals tapped as future leaders in the field—graduates of Winterthur’s museum programs at the University of Delaware—and elucidated nine trends that now challenge museums.

Education versus learning

Most critical to her is the changing American demographic. “If you take away nothing else from my talk, take this: In 2018, 60.4 percent of America was (still is) white, but by 2043 we will be a nation where citizens of color will be the majority.” Staff and boards must be as diverse as the audiences they attract and serve.

Feldman cited the need to move from “educating” to inspiring “learning,” a natural human instinct. Activity facilitates learning, as she illustrated with two photos. In one, a group of students sat in front of a battlefield painting as someone spoke. In another, students posed like the figures in the same canvas. “Which group will remember this work more clearly?” she asked.

Another trend is the tectonic shift from “information” to “content.” Information in museums has traditionally been confined to printed materials and small labels on the wall. Scholarship is of course paramount, and people will always relate to authenticity, but—noting our infatuation with “geek culture”—Feldman said that museums must tailor content to curiosity via computers and digital media.

New boundaries

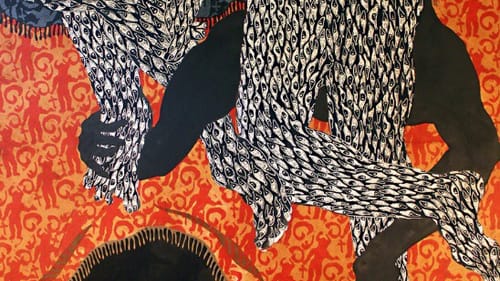

As boundaries and borders disappear, we can no longer categorize artists by nationality. Younger audiences—unfettered cultural omnivores—seldom view things nationalistically. To them, culture is defined by activities, not geography.

Feldman also promoted the need to create a consumer-oriented, flexible experience. People who come to museums are often stressed, requiring a transition to the serenity on offer. This happens at the entrance. She cited the Museum of Old and New Art in Hobart, Australia, whose multiple welcoming spaces include a wine bar and settings for quiet experiential moments.

Museums also must move from opacity to transparency. Many are now doing so by putting collections online or more directly facing issues of origin and provenance (such as the trail of ivory or looted art).

Funding and focus

Feldman has addressed funding challenges, like more art to care for and fewer big funders, by moving to “micro-funding,” shifting focus from fewer high-end patrons to smaller contributions from more people. In Minnesota, to encourage loyalty she offered both free admission and free membership, tracking the interests of those who joined.

Museums must move from traditional displays to real-world effects, determining “more carefully what we do with what we have.” In Minneapolis, Feldman started the Center for Empathy and the Visual Arts to address directly the impact of art in healing and health. She also cited the focus of Ohio’s Toledo Museum of Art on visual literacy, which encourages people think critically about what they see.

What remains

Taking her own advice to remain connected to what’s happening, Feldman punctuated her lecture with humorous photos from the recently triumphant Washington Nationals, her adopted team. And she closed by saying that in spite of shifting ground, the primary driver in an art museum will always be the work of art and the worlds it opens up.

Asked what will be different in 20 years, she said, “Everything and nothing. Programs and activities may change, but looking at art will remain at the core.” In this time of transition, she encouraged young museum leaders to consider carefully and creatively how different the future will look and how to meet it—something for everyone in the arts to ponder.

What, When, Where

Museums in a Radically New Time, Lecture by Kaywin Feldman, Director, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. This event was organized by current Winterthur Fellows and sponsored by the Society of Winterthur Fellows. November 8, 2019 at Winterthur, Wilmington DE. (302) 888-4600 or winterthur.org.

Winterthur is a wheelchair-accessible museum, with wheelchairs available to borrow onsite at no cost. Information on other accommodations, including ASL interpretation and assistive listening systems, is available here.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Gail Obenreder

Gail Obenreder