Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Trigger unhappy: warnings that get in the way

“I’m going to do a section in Helen’s voice,” my writing pal Amy Schutzer said as she prepared for a recent reading at Mt. Airy’s Big Blue Marble bookstore. “Do you think I should warn people that she’s dying of cancer?”

Helen is one of nine characters who narrate Schutzer’s new novel, Spheres of Disturbance, and the story takes place over a single day preceding her death. In the chapter Schutzer planned to read, Helen makes lists of things she will miss about life (walking at dusk; the library; wind chimes), muses over her treatment for metastatic breast cancer, and thinks angrily about her doctors’ insensitivity.

“Are you asking if you should give people a trigger warning?” I said. My friend glanced up from her own copy of the book, its spine bent from use, its pages annotated with pencil scrawls from previous readings. She looked unsure.

Proceed with caution

And no wonder. Last spring, the concept of “trigger warnings” — long used in feminist chat rooms and self-help blogspaces to flag users about graphic content related to sexual assault or rape — spilled over to the academic world.

Student leaders at the University of California, Santa Barbara, passed a resolution calling for such warnings — that is, notes on syllabi to alert students that certain books, articles, or films might trigger a traumatic reaction. The students’ list of potentially disturbing themes included sexual assault, suicide, graphic violence, and kidnapping.

We’re not talking about pulp fiction here. At Rutgers University, a student op-ed urged trigger warnings for novels such as Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway (suicide), Junot Diaz’s This Is How You Lose Her (domestic abuse), and F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Great Gatsby (graphic violence).

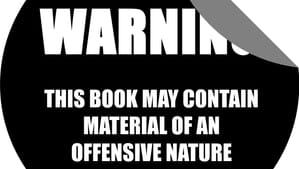

The trumpet for trigger warnings, which has also sounded at Oberlin, George Washington University, and elsewhere, is a cry we should heed — but not by tagging works of art with warning stickers.

Instead, we need to listen closely to what’s behind the call. Today’s college kids hail from a dizzying range of backgrounds and experiences: They may be international students from a country mired in tribal war; they may be first-generation Americans. They may have been bullied for their race, their accent, their gender expression. They may have been raped.

Or they may have experienced all-too-ordinary family trauma — physical abuse, neglect, a parent with a mental illness or an addiction. A groundbreaking 1998 study of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) showed that such adversity is as common as dandelions; almost two-thirds of respondents had childhoods pocked by at least one ACE.

In short, there’s a lot of suffering out there. And when college students pack that trauma into their duffel bags, university mental health services need to be prepared: with trauma-sensitive counseling, support groups, and campus-wide education efforts.

Barricading the ivory tower

What happens in the classroom is a different story. College classes should be places to unpack myths, challenge the status quo, try on alternate points of view and, yes, sometimes squirm in discomfort.

I know I did, my senior year of college, when we read Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man and grappled with the raw pain of racism and the white privilege that abets it . . . or when John Hersey’s Hiroshima distilled war’s crude and careless damage to the scale of individual lives . . . or when The Yellow Wallpaper by Charlotte Perkins Gilman plunged us so deep into the suffocating life of a 19th-century woman that I had to stop reading and take deep breaths between paragraphs.

Literature is meant to affect us. To shock us. Anger us. Transform us. And when we encounter it, in a community of other learners, in the guided space of a university classroom, it can even help to heal. Graphic accounts of war written by survivors teach us something about resilience and grit. Dorothy Allison’s Bastard Out of Carolina, based on her experiences of sexual abuse by her stepfather, shows us that all people, even abusers, are multidimensional and that empathy and judgment can coexist.

A trigger warning on that book might protect a reader traumatized by her own childhood abuse from revisiting those painful episodes. But it could also rob her of the chance to see how Allison made meaning of her hurt. Art can hold a crucial message for those who suffer. I survived, it says. You can, too.

J’excuse

If trigger warnings work as students hope — allowing those who might be triggered to excuse themselves from that reading assignment or film clip or class — they will also shrink the opportunities for meaningful conversation about the most troubling concepts of our time.

Professors may opt to leave volatile books off the list rather than risk repercussions. They may tame their syllabi in an effort to keep the classroom “safe.” And if they do use trigger warnings, students themselves — those with trauma and those without — will prejudge complex works of literature based on bumper-sticker summations: Surely Mrs. Dalloway is about more than suicide, just as The Great Gatsby offers perspectives on power and greed alongside that awful car crash.

In any case, where do you stop? Nearly any work of literature worth reading at the college level contains something that might disturb someone: accounts of slavery, religious persecution, the displacement of Native Americans. Gay-bashing. Female genital mutilation. I’m picturing novels plastered with color-coded stickers: a bright red V if the book contains violence; a chartreuse S if there’s self-injury involved.

Wouldn’t it be better to let college students encounter such works without prejudgment and make sense of them through dialogue, argument, and written response? Wouldn’t it be more respectful to assume that they are sturdy enough to wade into the words and use them to illuminate their own stories, to enlarge their take on the world?

At the bookstore reading last week, Schutzer gave no cautionary preface. She simply introduced Helen and let her speak: “In her war against cancer, the doctor’s tired phrase, there are secrets, what the cells are doing, and prisoners . . . . There is the trembling. . . . There is the pain.”

What would she have warned us against, anyway? The book is about life — and death, the trigger that, ultimately, will point to every one of us. Terrifying. Clarifying. I like to think everyone huddled in the bookstore that night felt a chill as they listened to Schuzter read about Helen’s last day and a resolve to cling ever more tightly to their own.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Anndee Hochman

Anndee Hochman