Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

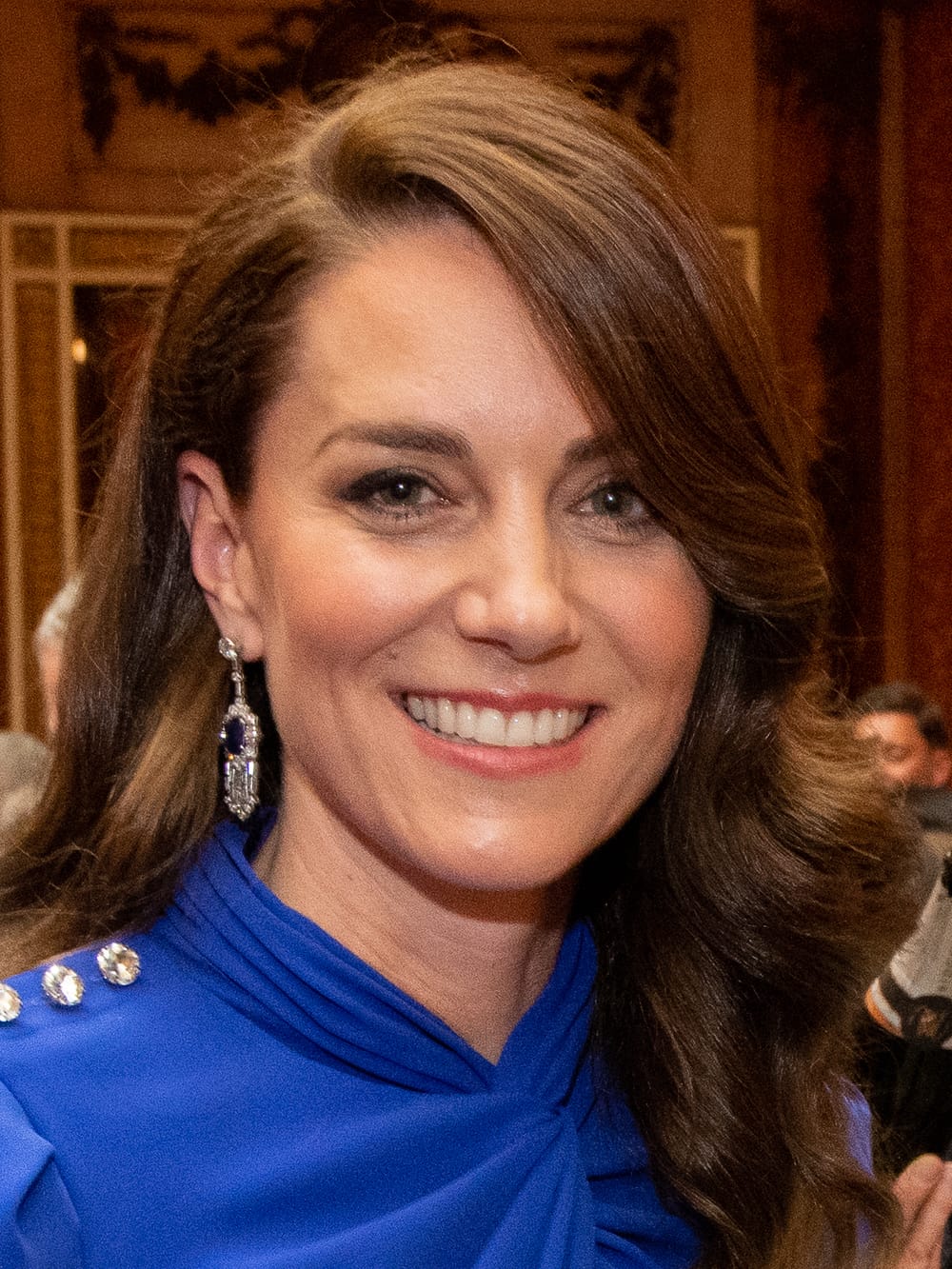

Before and after, for Kate and for me

Kate Middleton’s cancer diagnosis could remind us to stop projecting our own fears of illness and death.

I don’t care about the British royal family. Before last week’s video announcement of her cancer diagnosis and treatment, I’d had a neutral feeling towards Kate Middleton, the Princess of Wales. But on Friday afternoon, I texted a friend who is a fellow cancer survivor, someone who supports me in the annual purgatory between my mammogram and the results.

I asked her if she’d heard about Kate. She wrote back: “We knew, right?”

We knew.

Outside the fairy tale

I was nine when Lady Diana married then-Prince Charles. I woke up early to watch what was supposed to be their fairy-tale nuptials with my excited mom. I didn’t get it. I was a kid drawn to witches and wolves.

If I were a British citizen, I might be outraged that my tax dollars go to support the monarchy. But I’m an American and keep my rage focused on what’s happening right here—mainly the threat of losing our democracy.

Sharing Kate’s news

So I was surprised by my intense engagement last Friday afternoon when a news alert about Kate Middleton’s cancer diagnosis distracted me from pre-weekend work deadlines. I stopped everything to watch Kate’s video. I listened to TV commentary about her diagnosis. Emotions and memories bubbled up as I watched, including my own breast cancer diagnosis when I was 37 when my children were just six and three.

That was 15 years ago, but hearing Kate’s news brought it back: finding a lump when I was showering, thinking that it was nothing but calling to make an appointment, my first mammogram ever, getting the phone call from the doctor, telling my husband, imagining my children’s life without me, going through surgery then chemo, losing my hair, finding something to wear on my head, vomiting in the middle of the street when nausea came on suddenly, dropping my kids at preschool then driving to treatment, standing on the steps of the Art Museum doing yoga with other women going through the same thing, needing daily radiation at the same time my son was starting kindergarten, ringing the bell at the end of my treatment. Standing in that room at Fox Chase, bawling and laughing, shocked by the depth of my relief as total strangers stood and clapped for me.

The prayers and the paradox

My life is separated by before and after going through cancer. That same kind of before-and-after will be part of Kate’s life now. I’ve added her to my daily prayers for healing, this woman whose outer life experience couldn’t be farther from mine. Because more than anything else, it was the forcefield of healing prayers and energy, especially from women who had gone through cancer themselves, that lifted me up during those months of treatment and waiting.

Illness of any kind cuts across class, culture, religion, race, and other constructs created by humans. We’re living in a healthcare paradox: incredible medical breakthroughs happening and also shocking inequity in access to care; a time when life expectancy is increasing beyond what could have been imagined for some parts of our population, yet there is no plan for supporting people who live decades beyond retirement age. It’s not surprising that conversations about illness evoke fear and anxiety.

“I never thought this could happen to you”

Going through cancer at a young age was a catalyst for examining my mortality. I’ve done a lot of work in this area since then and have experienced incredible transformations in both my appreciation of life, with all of its difficulties, and acceptance of death. Most of my writing now is about spiritual practice, and I’m recently certified as a Jungian-based spiritual director because issues of grappling with existence and meaning-making interest me more than anything else.

No one needs to go through illness to become more conscious of feelings about facing mortality. There is a growing movement to demystify death; I have friends who are death doulas, and I’ve attended death cafés where folks can openly talk about end of life in order to remove fear and embrace life.

Facing unconscious fears around cancer could transform both our collective reaction to celebrities getting a diagnosis and the way we respond when people close to us receive that news. Otherwise, projection of those fears becomes damaging. I’ll never forget one experience of that after I shared my diagnosis with my synagogue community. One woman, older than me by a good 20 years and, in fact, a psychotherapist sent me a note that said, “I never thought this could happen to you—you’re so young, pretty, and funny!”

Her lack of awareness astonishes me to this day. Youth and any other qualities we associate with life don’t protect us from cancer; it can happen to anyone. I took the card out to my backyard and burned it with a match and laughed outrageously. Dark humor and a touch of witchcraft play a significant part in my survival.

What the news can mean for us

I can’t imagine how Kate will learn to protect herself from projections when her every movement is magnified in the public eye and reported in the tabloids. I hope the kind wishes that have been expressed since Friday weren’t a momentary blip and that they will keep on going. I pray that she gets some privacy while going through treatment and that she has access to emotional as well as physical care.

This collective news is an opportunity for each of us to look inward, to notice what is stirred up around her diagnosis. To consider ways that we react, and whether we support people facing illness in our own circle of friends, family, and community—or avoid them.

We can invoke compassion when we read the news, when we choose what kinds of memes to post, when we reject conspiracy theories of any kind, when we respond to our own hurt and fears with the honesty and authenticity that they demand.

At top: Catherine, Princess of Wales, in 2023. (Photo by Ian Jones, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Gabrielle Kaplan-Mayer

Gabrielle Kaplan-Mayer