Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Ode to joy

Corned beef and Beethoven, a hash-up

When I was in Phoenix recently for a radio conference, I wanted to escape the hotel for breakfast. I walked across the street to a rough-hewn restaurant where corned beef hash was on the menu. And so, I set my chin and nodded the chin-set nod of the optimist. At first, I thought, No, hash is either too dry or too greasy, edible only by way of poached egg, or ketchup, or by washing it down with coffee.

But, the adventurous southwest stoking my optimism, I ordered the hash. While waiting for its arrival, I looked blankly through the menu at everything I could have ordered. Pancake stacks, slices of French toast, and heaps of huevos rancheros mocked me.

Then I looked up.

The kitchen door opened and the waitress, backlit by fluorescence and haloed by steam, walked toward me carrying a plate. The glow from the kitchen suffused the room and lingered. The faces of other hotel escapees slowly turned as they followed the plate. A couple reached across their breakfasts and lightly clasped hands. Boz Scaggs, singing “Look What You’ve Done to Me” over the sound system, dropped to a whisper. The waitress approached, stopped, lowered the dish, and placed it silently in front of me, as an offering.

Bless this mess

You think I am exaggerating, but I am telling you, I noticed all this and noticed that I was noticing this. I mouthed, “Thank you,” but I do not know if the words came out. I beheld my breakfast. I glanced up just to catch her smiling as she turned.

The onions in a medium chop were on the cusp of translucence, shining with the bright dreams of youth. The potatoes were what potatoes always might be, but rarely are. Not dry, not oily, not hard, not mushy, they were fully and softly potatoes, luscious.

And then, the meat. We take for granted that corned beef hash is made from corned beef, but the Ding an sich is lost, always lost. This, however, this corned beef, was sliced into strips, and gently laid to one side. Bite-sized, they were fried, their edges crisp, their demeanor Buddha-like, their immanence ever present.

I stared at the plate, and, giving thanks with eyes open, bemusedly reached for my fork. I gently pierced one strip of the meat, put it into my mouth, and an entire life of breakfasts swooped me through years and decades and fixed me into that moment. Joy made room for discernment as I tried to enunciate why this was better than any hash I had ever eaten.

The heavens are telling

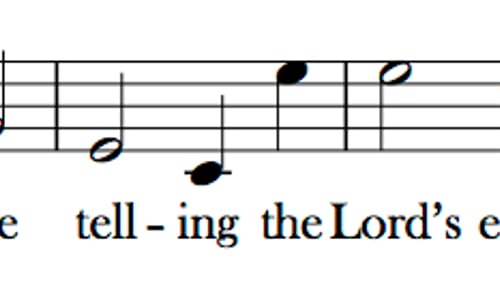

Again, you will think I am overselling, but I thought of Beethoven and his “Die Ehre Gottes aus der Natur.” We know it in English often as “The Heavens Are Telling.” Not to be confused with Haydn’s “The Heavens are Telling” from The Creation. Here is Beethoven’s:

I am serious. Beethoven came to my mind.

Beethoven gets to essentials quicker than any other composer. This is his greatness, and this is our problem. Beethoven is essential, but he is not pretty. He doesn’t entice us with the voluptuousness of Tchaikovsky, the wit of Mozart, the gravity of Bach, the warmth of Brahms — other composers we probably loved before Beethoven. No, he sticks his big saucer of a face into our business. His wild mane of hair pushed straight back looks as if he just forced his way, grunting, through a wind tunnel. We always hear that Beethoven is great, and we always say, “Yes, of course,” but our heart isn’t in it, not at first.

The opening of his Fifth Symphony we admire more than love. How clever he is to make all that music from those four silly notes, yes, yes. “Joyful, joyful” from the Ninth Symphony is exciting, but afterward the whole thing sounds, well, a bit brusque. “The heavens are telling” — not harmonized, mind you, and in the choral arrangement just octaves for everybody — is nothing but a C major triad, for crying out loud, followed by a big leap that looks like he just ran out of room.

Let it be

But at some point we succumb. Voluptuousness, wit, gravity, warmth, and everything else walk into the room. At 40, I finally got Beethoven. At 40, we realize that what we are is what we are going to be. For some, it’s a crisis; for me, it was liberation. I’m not unique in that. It happened to Brahms, and at that age: that fist-shaking opening to his First Symphony is not him screaming that he could never follow Beethoven; it is Brahms roaring: I am not you! I think Beethoven smiled right then.

At 40, hearing Beethoven on the radio yet another time (it was his Second Symphony, of all things), I got him, and I got that I could be me. I couldn’t be Bach, or Mozart, or Brahms, and (I whispered only to myself), they couldn’t be me.

Then I knew in the glowing restaurant why this was the best hash I had ever eaten.

The potatoes were not meretriciously tantalizing and then cold-hearted inside, but were simply and fully potatoes to the end. The onions were nothing more nor less than onions, but if you’ve ever worked them, you know that onions, like the universe, are onion all the way down.

The corned beef hash, you have guessed by now, tasted like what it never tastes like. It tasted like corned beef. Perhaps I forgot to tell you, but I love corned beef. And that opened up to me endless glory.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Kile Smith

Kile Smith