Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

The last one in South Philly without a tattoo

What getting my first tattoo taught me about body acceptance

“I think I’m the last person in South Philly who doesn’t have a tattoo,” I told the young artist as his black-gloved fingers gripped my right arm and firmly swiped it with antiseptic, the brief, icy-wet chill stinging my nose and making my heart speed up. After almost 40 years, my body has learned that disinfectant means something painful is about to happen.

“No, there are still some good Catholics walking around who’ll never come in here,” the artist replied, studying my skin.

I’m not religious (anymore), but I can relate to the feeling that there are inescapable rules about what I can and can’t do with my own body (of course, many religious people, including Catholics, do have tattoos). Somehow, as soon as I convinced myself that it wouldn’t be that big of a deal to get some ink, I realized that I was facing worries that have held me hostage since childhood.

Bad culture, bad medicine

I always admired others’ tattoos, but I thought I could never join the club. Part of my hesitancy was a perennial fear of how others would judge my body—a body whose perceived imperfections did not deserve ornament, a reason to make anyone look twice at my freckled skin or my chubby limbs.

That touches on so many things I’d rather forget: the first time I decided I was too fat and felt guilty about popsicles (age 7); cafeteria lunches where I wouldn’t eat and hope the headachy emptiness I took to class was making me thinner; the diet I tried in my 20s that replaced two meals a day with cereal. The year I endured both a grueling divorce and major surgery and rehab, only to be congratulated with “you’re so skinny!” when I was able to socialize again.

My Christian upbringing also fed the sense that my body was something for others to judge or consume: getting sent home because the shorts I wore for a hot day in unairconditioned classrooms violated the modesty of the girls’ dress code; the pastor who called me “used goods”; and “health” lessons claiming that premarital sex meant pregnancy, disease, and a sad, lonely life.

My healthcare experiences didn’t help, either: the psychologist who scoffed at my worries; the gynecologist who called me a liar; the orthopedist who told me to get a psychiatrist; the urologist who laughed at my questions; the family doctor who told me to go to the gym when I came in for laryngitis. A few months ago, a nurse made a crude comment about my breast size and announced that her boyfriend had to stop taking the medication that I need to survive, because it made him really fat.

Given all that, it’s not surprising that I wondered how people with tattoos had so much confidence about what to do with their bodies, and weren’t afraid to let others see their bodies. But what if my body, too, is something to take ownership of, to celebrate and decorate, not tolerate and hide?

Will it hurt?

I didn’t even have to leave the neighborhood. I walked into Eastern Pass Tattoo Company on Passyunk Avenue (where a sign warns that they don’t tolerate art directors or half-steppers) with my design on a Monday, and on Tuesday afternoon, I gave artist Marco Mazzarelli my arm.

“I’m a little nervous about whether this will hurt,” I admitted as he poised the ink over my right wrist.

“You’ll be fine,” he said breezily. “Your adrenaline is going. Your body started it up as soon as you came in the door, whether or not you know it.”

It did hurt, like a fresh, tingling burn that didn’t spread much, but grew more intense as the minutes passed. I breathed deep and reminded myself of things that hurt much worse. An arthrogram. A migraine. Physical therapy.

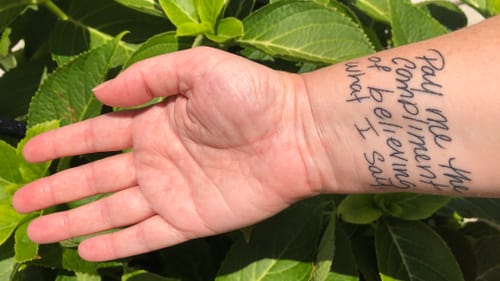

It was all over within 20 minutes. I admired the clean black script lodged for life on the soft underside of my lower right arm. It swelled a little and felt like bad sunburn for a couple of days, then got itchy. A few weeks later, it’s healed perfectly.

The compliment I need

My tattoo comes from Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, which has entertained and comforted me through decades of dark times, from sleepless nights to hospital stays. The quote is in the chapter where Austen’s obsequious clergyman, Mr. Collins, keeps trying to flatter Elizabeth Bennet, instead of listening to her when she says she won’t marry him.

“Pay me the compliment of believing what I say,” she demands. Praise means nothing if it’s from someone who refuses to understand you. Real love lies in listening. The quote also reflects my intention to stay honest (with myself and others), even when it’s difficult. It’s a note to healthcare providers to respect me and take me seriously. And it’s a little reminder from my own body to a brain that hates to slow down and be vulnerable: believe what I tell you, whether it’s sickness, injury, or physical echoes of trauma. Give me gentleness and rest.

The handwriting is from someone who shows me steady, companionable care when I need it most, and always listens to me.

But maybe the best thing of all about the tattoo is now that I’ve explained all about it, I realize that it doesn’t matter what you think of it. It has meaning to me, and that’s enough—just like my own body.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Alaina Johns

Alaina Johns