Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Circling the Globe

What does the proposed Wilma Globe say about accessibility in the arts?

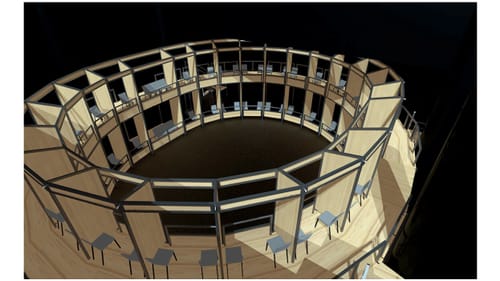

When I saw the announcement of the planned Wilma Globe, a two-tiered, circular audience structure that physically divides patrons while offering a view of an in-the-round stage, I wondered if the age of COVID-19 will finally make us agree that accessibility is something everyone should demand.

What and when?

The Wilma Globe nabbed a pile of positive coverage (including a short piece in The New York Times) that was a speedy nationwide remix of the press release. The Globe would have a circle of audience boxes on two levels, pairs of chairs separated by wooden dividers presumably impermeable to COVID droplets. Various seating configurations would welcome between 35 and 100 people at a time. Special cameras and tech-savvy direction would integrate the latest in livestreaming for those who can’t be there.

The proposed structure is designed to sit on the Wilma stage, but the timing is TBD—despite news reports indicating construction would begin in a few months (the Wilma has tentatively announced a return to live performances for late 2020, or early 2021, pending health decrees).

The backlash

The Wilma credits set designers Misha Kachman, Sara Brown, and Matt Saunders, along with video designer Jorge Cousineau, for developing the plan. As exciting as it is to see ideas, however rudimentary, for getting back into the theater, it’s worth noting that theater designers are not public-health experts, and many in the Philly theater community pointed out via social media that they found the release of the plans misleading and harmful, especially as COVID-19 infections are rising in cities across the country.

Renderings of the project also sparked ire from Facebook and Instagram followers for appearing to exclude people who can’t climb stairs (one Instagram user called the plan “a white ableist fantasy”).

“I do recognize that the images showcase the stairs up to the second level,” Wilma managing director Leigh Goldenberg told BSR this week. That was an unfortunate oversight in an animated rendering, she noted. “What the video doesn’t show is that the first level [of the Globe] is fully accessible.” Patrons using wheelchairs or other assistive devices would be able to access the first level of the Globe from a lobby elevator, and, Goldenberg said, it would be an increase in accessible seating from the Wilma’s traditional configuration.

A “fiasco”?

That’s good news, but it may not placate observers, who point out that we currently have no reliable guidelines for how performing arts venues may be reopened safely in the pandemic, however they are configured. Followers accuse the Wilma of grabbing publicity for a poorly developed concept that risks encouraging people to congregate indoors before it’s safe to do so.

“Just by announcing this before it was fully planned out you have wrought real damage on this community both locally and nationally,” insists another Instagram user, who worries that other institutions with fewer resources will now be pressured to manufacture similar questionable plans. Another commenter called it “a horrifying fiasco.”

In Instagram and Facebook posts, the Wilma promised a statement to address these concerns, a version of which came late Monday night: “We intended to share more details about the Globe today, but in an effort to be as thorough and transparent as possible, we are taking more time to complete this update.” As of this writing, there’s nothing addressing the controversy on the company’s website, which still touts the new plan along with a subscription drive.

No secrets?

Goldenberg said 2020-21 lead artistic director Yury Urnov sparked the plan, which was in development for two months before the announcement. Other theaters have been sharing their concepts for life after COVID, and Wilma leaders wanted to float their idea, too, she explained.

“Before we know that it’s definitely happening or when it’s happening, before we buy lumber and metal, let’s get it out into the world,” Goldenberg said of their reasoning. She pointed out that productions, many of which are “iterative and collaborative” community events, are routinely announced 10 months in advance of their staging, and the Wilma made its announcement in that spirit.

“Doing this in secrecy didn’t feel in line with the way that we work,” she said of sharing the plans. “I don’t know that there was an ideal time.”

Not a niche

Whether or not the Wilma made the right move in promoting its Globe when so many questions remain unanswered, the COVID-19 pandemic is an ideal time to think about accessibility—and the Globe concept should be a welcome entry to the discussion.

In a 2018 piece on accessibility at the Philly Fringe, I quoted local disability advocate Elizabeth Clay, who says, “People with disabilities are not a niche audience.” To me, this applies both to the fact that people with disabilities are not a monolith—their interests are as diverse as anyone else’s—as well as the reality that anyone, at any time, can experience disability, whether temporary or permanent.

That’s never been truer than today, when every single person who ever enjoyed going to the theater or making theater faces a physical barrier: anytime we congregate, we risk exposure to a deadly virus. The race to find a solution that allows us to reopen our cultural life—whether it’s through public policy, science and medicine, new physical infrastructure (like the Wilma Globe), or some combination of these—could be framed as the biggest accessibility challenge we’ve ever collectively faced.

Bring that energy

And while we face it, let’s reflect on the fact that being shut out of the theater or other arts events is not a new experience for millions of people (including me). Today, despite modern policies mandating access, some people with disabilities stay largely at home on a permanent basis because of societal failures that range from transportation to finance to physical buildings. If COVID inspires us to imagine whole new approaches to the art form within mere months, we should ask why we haven’t applied that urgency to other questions of access before the pandemic.

Despite obvious problems with its approach, the Wilma has crafted a possible answer to how future theater spaces could look, assuming the novel coronavirus doesn’t disappear next month or next year. That’s great. There’s a lot of pushback about how accessible and safe the idea truly is. That’s even better.

Can we take that energy for accessibility and accountability, and apply it going forward (in the pandemic and beyond) to the Wilma, to every theater company, and to ourselves?

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Alaina Johns

Alaina Johns