Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

What the Pulitzer Prize didn't do for Hemingway (or any other writer)

The Pulitzer Prize, and other delusions

A Pulitzer Prize jury once recommended a friend of mine for its award for Newspaper Commentary, only to be overruled by the Pulitzer board. I tried to console my distraught friend by pointing out that Pulitzers, like all awards, are ultimately just popularity stunts bestowed by fallible humans.

I recalled the time I served on a newspaper award jury. We jurors were conscientiously sequestered on a Wednesday morning in a New York hotel, there to spend three days and nights reading newspaper articles and debating their relative merits. Needless to add, by noon Friday we no longer cared about their relative merits— we just wanted to get the hell out of that hotel and go party, the sooner the better.

"You've served on prize juries," I reminded my friend. "You know it's all a crock."

"You don't understand!" she wailed (correctly). "Once you win a Pulitzer, you can write your own ticket!"

Chance to celebrate

That was then. Last week the Pulitzer board declined to bestow an award for "Best Fiction" in 2011 on anybody, and the entire book publishing industry was distraught.

Pulitzer winners, the novelist and bookseller Ann Patchett explained on the op-ed page of the New York Times, "are written up in papers and talked about on the radio, and sometimes, at least on PBS stations, they make it onto television. This in turn gives the buzz that is so often lacking in our industry…. The Pulitzer Prize is our best chance as writers and readers and booksellers to celebrate fiction."

Even if you assume, as Patchett does (and I don't), that the Pulitzers exist to serve the spiritual and commercial needs of writers and booksellers, the question remains:

Given the diversity of human tastes and the limitations of human time, how could members of any committee presume to read some 300 nominated works of fiction, many of them large and complex novels, much less reach some consensus as to which one is best? Better you should choose the best spouse in America, or the best friend.

Picasso vs. Goya

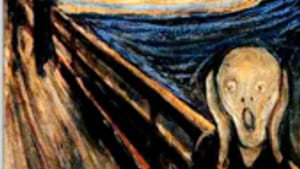

Come to think of it, how come there's no Pulitzer Prize for art? Couldn't all those starving artists in garrets use some celebration too? And wouldn't you love to see a prize jury deliberating among, say, Picasso's Guernica, Munch's The Scream and Goya's Disasters of War?

Maybe a Pulitzer would have transformed Mark Rothko into the life of the party instead of an insufferable grouch. If Van Gogh had won a Pulitzer, maybe he'd still have both ears. Or not.

More to the point: How, exactly, does winning a prize nurture anyone's creativity?

Did Hemingway's work improve after he won the Pulitzer in 1953 for The Old Man and the Sea? Harper Lee's after she won in 1961 for To Kill A Mockingbird? Allen Drury's after he won for Advise and Consent in 1960? (Answers below.)

Faulkner's day jobs

Yes, I know— a prestigious award can boost a struggling author's income, enabling her to give up her day job as a teacher or journalist to focus full-time on her fiction. But will doing so necessarily make her a better writer?

No novel by William Faulkner, I'm told, ever sold more than 6,000 copies before he won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1949, when he was 52. Had Faulkner won the Nobel sooner, he would have sold far more books during his best creative years. He could have stopped wasting his time working in a post office or writing Hollywood screenplays. Perhaps he would have written more books, or better ones.

On the other hand, before winning the Nobel, Faulkner wrote 14 mostly great novels (The Sound and the Fury, As I Lay Dying, Light in August, Absalom, Absalom!, Intruder in the Dust, etc.). After his Nobel, he wrote just five, mostly of lesser impact (e.g., Requiem For a Nun and The Reivers). Maybe there's something to be said for working a day job instead of staring at a computer screen for eight hours while an assistant brings you milk and cookies.

Oh, yes— the answers to my rhetorical questions above:

Hemingway wrote virtually nothing after 1953, although he and his estate derived added commercial mileage by resuscitating earlier works that were previously unpublished— but I suspect they could have done that even without his winning a Pulitzer. Harper Lee, who's still living, hasn't written another novel in the 50-plus years since Mockingbird. Allen Drury, presumably inspired by his Pulitzer for his very first book, dashed off 20 more novels and four works of non-fiction in his remaining 38 years. I offer a free subscription to any BSR reader who remembers any of them.♦

To read responses, click here.

I recalled the time I served on a newspaper award jury. We jurors were conscientiously sequestered on a Wednesday morning in a New York hotel, there to spend three days and nights reading newspaper articles and debating their relative merits. Needless to add, by noon Friday we no longer cared about their relative merits— we just wanted to get the hell out of that hotel and go party, the sooner the better.

"You've served on prize juries," I reminded my friend. "You know it's all a crock."

"You don't understand!" she wailed (correctly). "Once you win a Pulitzer, you can write your own ticket!"

Chance to celebrate

That was then. Last week the Pulitzer board declined to bestow an award for "Best Fiction" in 2011 on anybody, and the entire book publishing industry was distraught.

Pulitzer winners, the novelist and bookseller Ann Patchett explained on the op-ed page of the New York Times, "are written up in papers and talked about on the radio, and sometimes, at least on PBS stations, they make it onto television. This in turn gives the buzz that is so often lacking in our industry…. The Pulitzer Prize is our best chance as writers and readers and booksellers to celebrate fiction."

Even if you assume, as Patchett does (and I don't), that the Pulitzers exist to serve the spiritual and commercial needs of writers and booksellers, the question remains:

Given the diversity of human tastes and the limitations of human time, how could members of any committee presume to read some 300 nominated works of fiction, many of them large and complex novels, much less reach some consensus as to which one is best? Better you should choose the best spouse in America, or the best friend.

Picasso vs. Goya

Come to think of it, how come there's no Pulitzer Prize for art? Couldn't all those starving artists in garrets use some celebration too? And wouldn't you love to see a prize jury deliberating among, say, Picasso's Guernica, Munch's The Scream and Goya's Disasters of War?

Maybe a Pulitzer would have transformed Mark Rothko into the life of the party instead of an insufferable grouch. If Van Gogh had won a Pulitzer, maybe he'd still have both ears. Or not.

More to the point: How, exactly, does winning a prize nurture anyone's creativity?

Did Hemingway's work improve after he won the Pulitzer in 1953 for The Old Man and the Sea? Harper Lee's after she won in 1961 for To Kill A Mockingbird? Allen Drury's after he won for Advise and Consent in 1960? (Answers below.)

Faulkner's day jobs

Yes, I know— a prestigious award can boost a struggling author's income, enabling her to give up her day job as a teacher or journalist to focus full-time on her fiction. But will doing so necessarily make her a better writer?

No novel by William Faulkner, I'm told, ever sold more than 6,000 copies before he won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1949, when he was 52. Had Faulkner won the Nobel sooner, he would have sold far more books during his best creative years. He could have stopped wasting his time working in a post office or writing Hollywood screenplays. Perhaps he would have written more books, or better ones.

On the other hand, before winning the Nobel, Faulkner wrote 14 mostly great novels (The Sound and the Fury, As I Lay Dying, Light in August, Absalom, Absalom!, Intruder in the Dust, etc.). After his Nobel, he wrote just five, mostly of lesser impact (e.g., Requiem For a Nun and The Reivers). Maybe there's something to be said for working a day job instead of staring at a computer screen for eight hours while an assistant brings you milk and cookies.

Oh, yes— the answers to my rhetorical questions above:

Hemingway wrote virtually nothing after 1953, although he and his estate derived added commercial mileage by resuscitating earlier works that were previously unpublished— but I suspect they could have done that even without his winning a Pulitzer. Harper Lee, who's still living, hasn't written another novel in the 50-plus years since Mockingbird. Allen Drury, presumably inspired by his Pulitzer for his very first book, dashed off 20 more novels and four works of non-fiction in his remaining 38 years. I offer a free subscription to any BSR reader who remembers any of them.♦

To read responses, click here.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Dan Rottenberg

Dan Rottenberg