Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

A couple, their building, their city, and their world

The ‘good life’ in New York, redefined

The year was 1968. Antiwar protesters marched in the streets. Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy had just been murdered. Lyndon Johnson floundered helplessly in the White House. From their spacious old apartment on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, my parents — Herman and Lenore Rottenberg, then in their early 50s — pondered an eternal question: how to make the world a better place.

Dad, having sold his knitted wear business in 1962 to spend his time promoting international goodwill through folk dancing, was reinventing himself as a cultural impresario. Mom was championing the cause of urban mass transit for the Women’s City Club and providing English conversation to newly arrived immigrants at Manhattan’s International Center.

In many respects, their home at 300 West End Avenue seemed an ideal location for such a pair of idealists. Nearly half of that building’s two-dozen tenants were celebrities of some sort (like the flutist Julius Baker, the ventriloquist Paul Winchell, the dancer Sono Osato, the Hearst columnist George Sokolsky, and the City Council president Rudolph Halley). It was said to be the only Class A apartment building below 96th Street willing to rent to blacks, and consequently it attracted such luminous tenants as Harry Belafonte and Lena Horne. Beginning in the late 1950s Belafonte turned his 21-room apartment into a meeting place for the Civil Rights movement; Martin Luther King and Ralph Abernathy often stayed there when they came to New York, and John F. Kennedy himself paid a visit during the 1960 presidential campaign.

Dinner with Martin Luther King

In the process of converting 300 West End from a rental building to a co-op in 1961, my parents had developed a close friendship with Belafonte, whose sheer personal magnetism inevitably drew them into the fringes of the Civil Rights movement. Belafonte was (and still is) a master at enticing others to serve causes greater than themselves. One day when King and Abernathy were his houseguests, Belafonte phoned my parents to ask a favor. “I’m busy tonight,” he explained, “and Martin and Ralph have nothing to do. Could you take them out to dinner?” Of course my parents did.

These heady brushes with fame notwithstanding, by 1968 both my brother and I had grown up and moved away, and Mom was eager to downsize from their ten-room apartment. Dad resisted the idea of moving. But somehow Mom steered him to the Majestic, the legendary twin-towered Art Deco skyscraper on Central Park West at 72nd Street. As soon as Dad walked into Apartment 18-D, with its view of Central Park and its two terraces, he announced, “We’ll take it!” without even inspecting the remaining rooms.

It soon developed that my parents had acquired more than an elegant apartment with a spectacular view. In the heart of that city of unbridled ambition and constant change, they had somehow stumbled upon a vertical community of civility and continuity. Many of my parents’ new neighbors, like many of the building’s employees, had been at the Majestic since it first opened in 1931. Jimmy Cohen, my parents’ next-door neighbor, had actually been carried into the Majestic as a newborn baby by the same doorman who, more than 30 years later, still hailed cabs outside the front door. Since 1957, more than 200 highly individualistic Majestic residents had taken the then-extraordinary step of trusting each other to engage in one of New York’s first co-op ventures — a novel and risky form of business partnership in which a single rogue neighbor could ruin not just the neighborhood but his neighbors’ investment as well.

Fireworks and marriage proposals

My parents soon realized that their apartment was the ideal vehicle for introducing foreign visitors to New York at its best. They began hosting gatherings for Dad’s performers, as well as foreign graduate students at International House, where Dad spent 45 years as director of special cultural programs. Like most foreign visitors, these bright and talented students had initially found America and New York intimidating. Few of them had ever set foot in a private American home. But at 18-D they developed a genuine affection for their host city and country. On New Year’s Eve and the Fourth of July, they would cluster on the terraces to watch the fireworks, toast the holiday, and, occasionally, propose marriage. On Thanksgiving, they’d come to see the parade. On Dad’s birthday and numerous other excuses for parties, they’d push back the furniture and dance.

(When Dad’s downstairs neighbors understandably complained, Dad came up with an ingenious solution worthy of such an affluent community: Whenever he threw a party, he bought his downstairs neighbors two tickets to a Broadway show that night.)

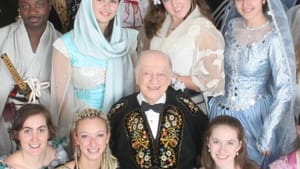

After Mom died in 1981, Dad’s student visitors became his surrogate family. Over 45 years, hundreds of them partook of the joys of 18-D. Many of those protégés subsequently returned to their native lands to become major corporate executives, prominent performing artists, government officials, even kings and queens — always harboring warm thoughts about New York and the U.S.

Shrewd investment

After Dad stopped working at the age of 91, his greatest pleasure was to sit on his bedroom terrace at dusk with his protégés, drinks in hand, watching the sunset reflected in the glass façades of the Fifth Avenue buildings across Central Park. Even after Dad died in November 2013 at the age of 97, many of his protégés continued to return to 18-D to bask in their memories of those rooms.

This summer my brother Bob and I finally sold 18-D, concluding 47 years of the Rottenberg family’s presence in the Majestic. In the course of those 47 years, the apartment’s value multiplied more than 90 times — perhaps the shrewdest financial investment our parents ever made. But of course it was never about the money. It was what our parents saw in their home as a tool for enhancing their lives as well as the life of their city and their world.

The apartment’s value appreciated for many diverse reasons, of course. But surely one reason was that, in the course of those 47 years, New York became a more appealing place to live. In that case, it’s comforting to think that our parents — and, to be sure, many other New Yorkers like them — helped make it so. It’s also comforting to imagine that, even as we speak, much the same sort of transformation might be taking place here in Philadelphia.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Dan Rottenberg

Dan Rottenberg