Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

The thrill (and emptiness) of an Eagles victory

Sublime moments, real and contrived

“This night will be remembered for decades in Philadelphia,” wrote Zach Berman in the Inquirer, “when old friends reminisce about where they were on Feb. 4, 2018, and parents tell their children about the moment the Eagles won their first Super Bowl.” Only slightly less hyperbolically, the New York Times informed its readers: “In the grand old city with the grand old football tradition, they will scale light poles and drive dune buggies up the steps of the Philadelphia Museum of Art and chant 'Fly Eagles Fly' until their voice vanishes. The party will rage for months, because the improbable has happened.”

Well, yes. In this slog otherwise known as human life, everyone needs an occasional sublime moment to sustain us through the miserable toil and struggle to come. Some of us might find sublimity in artistic events, such as the New York Armory Show of 1913 or the opening night of Beckett’s Waiting For Godot in 1953. But if the victory of an underdog professional football team that hadn’t won a championship in 57 years — led by an obscure backup quarterback — over a seemingly invincible dynasty, in a contest witnessed by 100 million people and celebrated by sportswriters (and even politicians) from coast to coast, in a manner that united urban Philadelphians and suburbanites in a rare sense of shared community, strikes you as a sublime moment, surely you are entitled to share it with your grandchildren someday.

Still, when the clock expired Sunday night at U.S. Bank Stadium in Minneapolis, green confetti showered the field, and Eagles players dumped a celebratory cask of Gatorade upon coach Doug Pederson, I found myself recalling a similar celebration that took place in January 1961 when my prep school, the Fieldston School in New York, finally defeated its despised basketball rival, the Barnard School for Boys.

These two schools had hated each other since before I was born. During my six years at Fieldston, we played Barnard’s basketball team 12 times and lost all 12 games, usually by lopsided scores. Can you imagine the frustration and anger that gnawed away at loyal Fieldstonites year after year?

Surrogate for war

Why, exactly, did these two schools hate each other so, and why did their faculties tolerate and even tacitly encourage such hostility? The trite answer is that they hated each other for the same reason Yale hates Harvard, Cambridge hates Oxford, Eagles fans hate Dallas, and France (once) hated Germany: because their parents, not to mention their parents’ parents, hated each other.

But ultimately some genuine pedagogical logic may have justified the Fieldston-Barnard rivalry. At least since the 19th century, educators have instinctively perceived the critical role played by sports in fostering two vital components of human achievement: competition and cooperation. These pedagogues recognized that such a perception is best conveyed in some practical and dramatic form, that the essence of drama is conflict, and that, short of the ultimate conflict — war — the safest and most effective surrogate might be an age-old traditional rivalry against a contrived enemy school conveniently located just a few city blocks away.

Pandemonium strikes

In the rivalry's final basketball game of my senior year, Fieldston managed, for the first time in my six years there, to hold Barnard’s margin of victory to fewer than 10 points. When that game ended, in my capacity as Fieldston’s co-captain, I melodramatically announced that no matter where I might be in the future, I would return to Fieldston for every Barnard basketball game until we beat them.

Fortunately for my future plans, Fieldston’s basketball team finally defeated Barnard the following year, when I was a freshman at Penn. And what pandemonium ensued when that game ended! Mobs of Fieldston students — some of whom had been in kindergarten the last time Fieldston won a basketball game against Barnard — stormed the court in a hysterical orgy of screaming, jumping, weeping, hugging, kissing.

And then, after 10 or 15 minutes of this mayhem, people started looking at their watches, gathering up their books, checking their homework assignments, and bumming rides home from seniors with cars. “It was the first time I realized how reality tends to disappoint expectations,” my younger brother Bob, then Fieldston’s basketball manager, recalled years later. “When the thing you were so looking forward to finally happens, how can you possibly express all your pent-up hopes in that moment? I remember thinking: Isn’t there more? Couldn’t there be more? Now we just go back to what we were doing?”

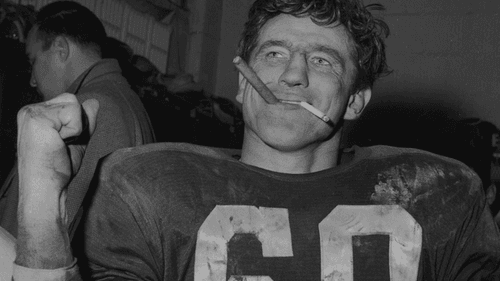

Bednarik’s greatest game

On this occasion of the Eagles’ long-overdue first Super Bowl championship, I will give the last word to the late Chuck Bednarik, the mainstay of Philadelphia's last National Football League champion team in 1960. During a radio interview in 1980, Bednarik was asked to choose the greatest game of his college career at the University of Pennsylvania. Without hesitation, he cited the 1948 Penn-Army game at Franklin Field, a seesaw affair witnessed by 78,000 fans, in which Penn held the lead three times against the heavily favored Cadets, only to lose in the final minute on a touchdown pass caught by Army’s Jack Trent.

The interviewer, a Penn student, expressed surprise: How could a heroic All-American figure like Bednarik choose a defeat as his greatest game?

You could almost hear Bednarik shrug over the airwaves. “Well, two years later Jack Trent was killed in Korea,” he explained. “When I heard that, I realized it was foolish to get too concerned over whether we won or lost a football game.”

The most sublime moment in Philadelphia sports history — the Athletics’ three-run ninth-inning walk-off rally that ended the 1929 World Series — involved a team that left town in 1954. For that matter, the Barnard School for Boys closed its doors in 1972.

But here is the good news: Godot is onstage in Philadelphia right now, and you can still spend the day at the Philadelphia Museum of Art basking in some of the work that once caused jaws to drop at that 1913 Armory show. What is truly sublime truly endures.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Dan Rottenberg

Dan Rottenberg