Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Woody Allen's mantra, plus a few kind words for football

In defense of football

At our team's last reunion before he died in 2006, my old Penn football coach John Stiegman challenged his former players— by then doctors, lawyers, investment bankers and executives in their 60s— to think about why we had played football in the first place, especially since we had experienced the thrill of victory so rarely (we never won more than three games in a season).

It was a pertinent question. Back in the day— before anyone knew about the long-range brain damage caused by football-induced concussions— most of us reflexively said we played for love of the game, or love of Penn, or for the sheer challenge. But when I reflected on the coach's question as a middle-aged adult, I found myself recalling a chance conversation in the dressing room one day before practice with a teammate, a defensive halfback named Bob Harris.

"You know, this is really great!" Bob said, without a trace of sarcasm or irony. "Every day we put on pads and spend 90 minutes running around a field and banging into each other. We get fresh air and terrific exercise, we work off all our aggressions— and when we're done, we're ready to hit the books!"

Among my teammates, Harris was widely dismissed as a flake or, worse, a closet intellectual. But in retrospect I can't think of a better rationale for the role of football in the context of a college education.

Dealing with adversity

Today it's widely accepted that football at all levels is out of control. Four years ago, the New Yorker writer Malcolm Gladwell compared football to dog fighting. Last December in BSR, the former Philadelphia Eagles quarterback Mike Boryla bitterly likened professional football to a "meat grinder." (Click here.) Last week in BSR, the retired professor Patrick Hazard denounced football for its disproportionate role in infantilizing American higher education. (Click here.)

These are valid criticisms, to be sure. Yet my own football experience as a lowly fourth-stringer at an Ivy League university was quite different. With each passing year I am struck by the critical role that football played in my education.

It was not in the classroom or on the Daily Pennsylvanian but on the football team that I learned to deal with adversity, to function as part of a team, to push myself beyond my imagined limits, to take criticism and to give criticism— all skills that have served me well in my adult career as a writer and editor.

This is precisely the way collegiate and scholastic sports are supposed to work. There is no academic justification for intercollegiate sports unless they provide some educational benefit to the students who play them.

Of course every sport teaches you to deal with adversity. But as degrees of adversity go, there's nothing quite like lining up against an opponent who outweighs you by 50 pounds.

Bednarik's jersey

I never thought about it much at the time, but in my day, any Penn student who wanted to play football could draw a set of pads and practice with the varsity. Some of those walk-ons, like me, eventually suited up for games and played in legendary stadiums like Franklin Field and the Yale Bowl. (I was living proof of Woody Allen's mantra: "90% of success in life is just showing up.") But regardless of size or ability, no student was turned away, any more than Penn would have turned a paying student away from a classroom.

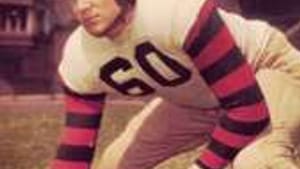

I recall one decidedly unathletic classmate named Ray Goodman, who came out for football because, he said, the regimen helped him keep his weight down. Ray practiced four days a week and sat in the stands on Saturdays. That experience alone was his reward— that, plus the opportunity, on the final day of the season, to don the same red-and-blue-striped jersey once worn by the likes of Chuck Bednarik and Reds Bagnell and sit with the team on the sidelines, just once.

Football may indeed be a more dangerous sport than I or any of my teammates ever dreamed. On the other hand, as Bob Harris put it, it did work off our aggressions with less risk than say, military service. Besides, as Jeremiah Ford, Penn's athletic director in my day, used to say, "If colleges eliminated football, the students would organize their own teams." Which is precisely how the first college teams began in the 1870s.

Why leave Rutgers?

Anything taken in excess is dangerous. Football is no exception. As a decidedly marginal player, I'm grateful to Penn for giving me the opportunity to play the game. I'd hate to see other kids lose that opportunity, just because the pros and big-time colleges have abused the game.

Before John Stiegman came to Penn, he spent four years at Rutgers, where he produced winning teams and coached several genuine All-Americans, like the tailback Billy Austin and the pro center Alex Kroll. My Penn teammates and I could never understand why he gave up that glory to coach a bunch of (we thought) losers like us.

At Stiegman's funeral in 2006 I put that question to one of his former Rutgers players. "Stiegman really believed in the Ivy League ideal," was his reply. "He thought a coach should be a teacher above all."

Stiegman understood what many critics of football have overlooked: There's more than one way to approach the game.♦

To read responses, click here.

It was a pertinent question. Back in the day— before anyone knew about the long-range brain damage caused by football-induced concussions— most of us reflexively said we played for love of the game, or love of Penn, or for the sheer challenge. But when I reflected on the coach's question as a middle-aged adult, I found myself recalling a chance conversation in the dressing room one day before practice with a teammate, a defensive halfback named Bob Harris.

"You know, this is really great!" Bob said, without a trace of sarcasm or irony. "Every day we put on pads and spend 90 minutes running around a field and banging into each other. We get fresh air and terrific exercise, we work off all our aggressions— and when we're done, we're ready to hit the books!"

Among my teammates, Harris was widely dismissed as a flake or, worse, a closet intellectual. But in retrospect I can't think of a better rationale for the role of football in the context of a college education.

Dealing with adversity

Today it's widely accepted that football at all levels is out of control. Four years ago, the New Yorker writer Malcolm Gladwell compared football to dog fighting. Last December in BSR, the former Philadelphia Eagles quarterback Mike Boryla bitterly likened professional football to a "meat grinder." (Click here.) Last week in BSR, the retired professor Patrick Hazard denounced football for its disproportionate role in infantilizing American higher education. (Click here.)

These are valid criticisms, to be sure. Yet my own football experience as a lowly fourth-stringer at an Ivy League university was quite different. With each passing year I am struck by the critical role that football played in my education.

It was not in the classroom or on the Daily Pennsylvanian but on the football team that I learned to deal with adversity, to function as part of a team, to push myself beyond my imagined limits, to take criticism and to give criticism— all skills that have served me well in my adult career as a writer and editor.

This is precisely the way collegiate and scholastic sports are supposed to work. There is no academic justification for intercollegiate sports unless they provide some educational benefit to the students who play them.

Of course every sport teaches you to deal with adversity. But as degrees of adversity go, there's nothing quite like lining up against an opponent who outweighs you by 50 pounds.

Bednarik's jersey

I never thought about it much at the time, but in my day, any Penn student who wanted to play football could draw a set of pads and practice with the varsity. Some of those walk-ons, like me, eventually suited up for games and played in legendary stadiums like Franklin Field and the Yale Bowl. (I was living proof of Woody Allen's mantra: "90% of success in life is just showing up.") But regardless of size or ability, no student was turned away, any more than Penn would have turned a paying student away from a classroom.

I recall one decidedly unathletic classmate named Ray Goodman, who came out for football because, he said, the regimen helped him keep his weight down. Ray practiced four days a week and sat in the stands on Saturdays. That experience alone was his reward— that, plus the opportunity, on the final day of the season, to don the same red-and-blue-striped jersey once worn by the likes of Chuck Bednarik and Reds Bagnell and sit with the team on the sidelines, just once.

Football may indeed be a more dangerous sport than I or any of my teammates ever dreamed. On the other hand, as Bob Harris put it, it did work off our aggressions with less risk than say, military service. Besides, as Jeremiah Ford, Penn's athletic director in my day, used to say, "If colleges eliminated football, the students would organize their own teams." Which is precisely how the first college teams began in the 1870s.

Why leave Rutgers?

Anything taken in excess is dangerous. Football is no exception. As a decidedly marginal player, I'm grateful to Penn for giving me the opportunity to play the game. I'd hate to see other kids lose that opportunity, just because the pros and big-time colleges have abused the game.

Before John Stiegman came to Penn, he spent four years at Rutgers, where he produced winning teams and coached several genuine All-Americans, like the tailback Billy Austin and the pro center Alex Kroll. My Penn teammates and I could never understand why he gave up that glory to coach a bunch of (we thought) losers like us.

At Stiegman's funeral in 2006 I put that question to one of his former Rutgers players. "Stiegman really believed in the Ivy League ideal," was his reply. "He thought a coach should be a teacher above all."

Stiegman understood what many critics of football have overlooked: There's more than one way to approach the game.♦

To read responses, click here.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Dan Rottenberg

Dan Rottenberg