Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Speaking of healing

How ‘I Have a Dream’ taught me never to apologize for the words I need to speak

I went to a writing workshop a few weeks ago and found myself spewing two handwritten, heartfelt pages following a handful of prompts. Hedged in my skin, I was on the brink of outpour. I volunteered to share, and apologized that my words were probably not very good—I hadn’t written spoken word since 2005. Still, something in me wanted out, and I was afraid I’d have to apologize for that too.

“You don’t have to apologize for who you are and what you have, Black man,” the moderator told me. Those were healing words in the midst of my deliberate vulnerability, something I’m not yet accustomed to.

Yet, I apologized for my apology.

Sorry not sorry

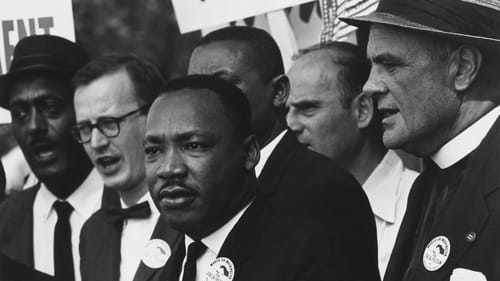

Apologies are vicious cycles. When a cycle has you, it’s difficult to find ways to articulate and understand the experience. You’re in the cycle, perpetuating over and over again what’s minimizing and diminishing you. This is how I perceive my own Black body and my own existence, and expressing that through the English language has long been a journey. And in the week of 2020’s Martin Luther King Jr. Day, I’m especially aware of how vital it is to continue that journey despite its viciousness.

Practice what you preach

A short video essay from Philly native Evan Puschak (AKA the Nerdwriter) explores how, with its allusions to Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address, the “I Have a Dream” speech frames the Civil Rights movement not as a singular phenomenon but as a chapter in American history. MLK’s opening words, "five score years ago,” echo Lincoln’s “four score and seven years ago.” King said “all men are created equal,” just as Lincoln did.

This links King’s speech and the Civil Rights movement to the founding of the nation and also the Civil War. The rhetoric “frames civil rights as a chapter in the larger American mythology so that those who identify with that mythology might incorporate this struggle into that story,” Puschak explains.

Welcoming devices

The video unpacks King’s speech even further, observing how frequent alliteration creates musicality. King also employs anaphora, or the repetition of a word or phrase at the beginning of successive clauses. If you can’t wrap your mind around that, think about your favorite Lil’ Wayne song—he uses anaphora often.

Anaphora, allusion, and alliteration are important here—not just because they are fancy literary devices used to elevate emphasis and organize ideas in a speech or in music, but because they help bridge the gap of understanding and compassion in an audience with wide-ranging experiences and perspectives. In a language that politically is manipulated to do the opposite: to alienate, isolate, and divide. Hear me out.

The winter of our discontent

“I Have a Dream” also references Shakespeare, nodding to Richard III: “This sweltering summer of the Negro’s legitimate discontent will not pass until there is an invigorating autumn of freedom and equality…. Those who hope that the Negro needed to blow off steam and will now be content will have a rude awakening if the nation returns to business as usual.”

Clichés can be powerful literary devices when used correctly. Puschak points out three clichés here: “blow off steam,” “rude awakening,” and “business as usual.” Clichés have potential because there is history built within them. What that history is, and whether or not it is true, is another thing.

Nowadays, the “business as usual” line is the scariest of the bunch in this context. “If the nation returns to business as usual” is like a premonition of “make America great again,” a turn of phrase that precipitates disquiet in my body as a Black person. I’ve borne physical insecurities and fears for my body since I was a child, long before MAGA rallies—and that stems from traumas I’ve experienced on my own and ones that have been passed down through generational trauma presaging MAGA’s values, so beguiling to many contemporary Republicans.

Running in the family

Generational trauma, or historical trauma, is “the cumulative phenomenon where those who never directly experienced trauma can still exhibit signs and symptoms of the trauma,” as Taasogle Daryl Rowe and Kamilah Marie Woodson write for an essay in The Conversation: “That historical trauma can be observed in African-Americans’ unresolved grief, expressed as depression and despair and their harboring of unexplained anger…. Often they internalize oppression by accepting the lie of inferiority, which can then lead to self-loathing.”

I live that. The spoken word that found its way onto the paper a few weeks ago was all about seeking freedom for my body and pushing against those feelings of inferiority and self-loathing. To not be reserved, suppressed, and oppressed in response to insecurities, fears, and traumas either experienced or passed down. It was a massive personal step forward, but one session of practice does not undo hundreds of years of being maligned, destroyed, and enslaved.

Yet, I apologize. Simply for my being. I don’t have the right words—including “I’m sorry.”

In your own terms

In a 1942 essay, George Orwell expresses frustration with the English language as it is used in politics. In modern English, he says, “no one seems able to think of turns of speech that are not hackneyed: prose consists less and less of words chosen for the sake of their meaning, and more and more of phrases tacked together like the sections of a prefabricated hen-house.”

It's not easy coming up with our own words. We’re often taught not to write in clichés, but we’re not taught what to do instead. How can our own experiences infuse terms that are understandable and inspirational, like King’s “I Have a Dream” speech?

Injustice then and now

Orwell goes even further, making allusions to problems that existed then with imagery that may not make sense in 2020, but still hits home. “Defenceless villages are bombarded from the air, the inhabitants driven out into the countryside, the cattle machine-gunned…this is called pacification.” Pacification today is when someone denies the experiences of marginalized people. And today, it’s not cattle that authorities are gunning down.

“Millions of peasants are robbed of their farms and sent trudging along the roads with no more than they can carry: this is called transfer of population or rectification of frontiers.” In updated words, gentrification.

“People are imprisoned for years without trial, or shot in the back of the neck or sent to die of scurvy in Arctic lumber camps: this is called elimination of unreliable elements.” Modern policing and the prison-industrial complex, anyone?

Worth a thousand words?

Long words, exhausted idioms, and clichés can maintain (or grow) the gap between one’s real experience and one’s desire or need to close that gap. These issues are political—all issues are, as Orwell insists (and I agree). Taking the time to research, craft, and cultivate our own words would help close the gap, arousing spoken truths that come as natural as the lyrics to my favorite Lil’ Wayne song or the lines of my favorite Shakespeare play.

I’ve been realizing, acknowledging, and opening up about my own personal traumas. It’s a journey, one that doesn’t end with me. So who knows. You might see me out here unapologetically performing spoken word in these streets someday.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Kyle V. Hiller

Kyle V. Hiller