Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

He made libraries sexy

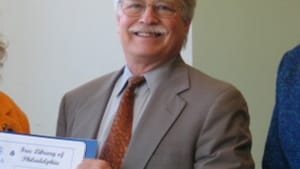

Elliot Shelkrot: Librarian as pitchman

Shortly after Elliot Shelkrot arrived at the Free Library of Philadelphia as its president and director in 1987, I commiserated with him over what seemed to me (and most other pundits) the Library’s fatal handicap: Back in 1951, the new City Charter had bent over backwards so far to protect Philadelphians from corrupt politicians that the Free Library seemed virtually powerless to respond flexibly to the needs of a changing society.

The Charter established an independent board of Free Library trustees. Most of them were appointed by the mayor for life, so they were really independent of politicians, but also totally unmotivated. All Free Library personnel, except for the director, were put under civil service, so they were hired and assigned by the city’s personnel office, just like all other city employees; the library’s director couldn’t even choose his own secretary. And the library depended on city and state government for 99 percent of its funding.

The result, as I described it in a 1984 Inquirer column, was a pervasive culture of begging: The Free Library trustees had to beg City Council for funds; the library had to beg the mayor for attention and support; and the director had to beg his subordinates to implement his plans. Although the Free Library system’s annual “attendance” exceeded the annual attendance of the Phillies, Eagles, Flyers, and Sixers combined (and still does), and although it had more registered card-holders than the local sports teams had season ticket-holders, the library's timid image would fail to seize the imagination of the public, the media, and politicians as long as it was restricted by the charter’s archaic rules.

Beautiful people

But Shelkrot greeted my litany of woe with a cheerful shrug. “The power to hire and fire is overrated,” he said. “There are other ways to motivate people.” As for the Free Library’s funding headaches, he added, “What’s important is to get the public’s attention — both to use us and to see how important we are.”

Shelkrot, who died last month at the age of 72, understood two big things. First, he been hired to make a difference, not to bemoan his limitations and wring his hands helplessly. Second, he perceived the value of leveraging publicity to raise money, and vice versa.

The board’s resuscitation of its long-dormant foundation in 1988 broke the Library’s no-win cycle of total public dependency. Soon the once seedy Central Library on Logan Square was hosting a full calendar of visiting authors, not to mention a lavish annual Borrower’s Ball as well as special events for the Free Library Foundation’s elite George S. Pepper Society (entry fee: $1,000). Such glamorous offerings drew Philadelphia’s Main Liners and assorted other beautiful people into a building they’d rarely set foot in, which consequently attracted media attention, which consequently attracted politicians and foundations eager to climb aboard a perceived bandwagon.

Farewell, Marion Paroo

Many people who’d never thought much about libraries began to take notice. When the Free Library Foundation raised $40 million from the likes of the Pew and William Penn Foundations for a system-wide modernization project in the 1990s, Mayor Ed Rendell’s administration committed $25 million despite the city’s own desperate straits.

One result: Although the city cut his budget throughout much of his 20-year tenure, Shelkrot transformed the city’s Free Library system from a musty refuge for bookworms into a state-of-the-art network of renovated and modernized branches boasting computers and Wi-Fi access at all 61 locations, nearly all open six days a week.

In a visual age, this transformation was a very big deal. Unlike visual images, letters are abstract symbols that the mind must assemble into words and sentences. Thus, when you read words, they trigger a thought process that doesn’t occur when you merely open your eyes or ears. If only for that reason, the future of intelligent human discourse depends on the written word.

Shelkrot understood that the future of the planet depends on librarians’ ability to generate enthusiasm for their product. He was no Marian Paroo, shushing patrons of the River City Library in The Music Man; nor was he Mary Hatch in It’s A Wonderful Life, doomed to a career as a mousy librarian because she couldn’t land a husband. He was a pitchman and a consensus builder, in the best sense of the word. He convinced his patrons, his employees, and his funders that the Free Library’s work was not only important but exciting as well. Philadelphians are indebted to him far more than most of us realize.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Dan Rottenberg

Dan Rottenberg