Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Dissent about the Lantern's "QED'

Ideas can be sexy, too

DAN ROTTENBERG

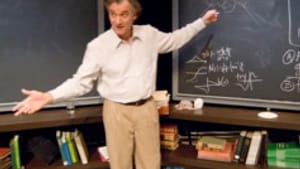

Permit me to dissent from Jim Rutter’s review of QED, currently offered by the Lantern Theater Company. Rutter finds the production “worth seeing for several reasons, chief among them to witness what a talented actor can achieve”— specifically, the remarkable Peter DeLaurier in the role of the late Nobel physicist Richard Feynman. Rutter’s quarrel lies with “Peter Parnell’s one-dimensional script, which fails to capture the magnitude of this remarkable man’s life,” which “reveals little and dramatizes even less.”

Rutter suggests that we’d be better off reading Feynman’s extensive writings, on which Parnell’s play is based. No doubt we would. Perhaps we’d also be better off reading the poems of T.S. Eiiot than attending Cats. But sometimes it takes a creative mind to perceive the dramatic stage possibilities in words on paper. Feynman has been dead for 18 years, and no one saw him as grist for a drama until Parnell come along.

And QED is indeed dramatic, even if the drama takes place entirely within Feynman’s head. The protagonist is a physicist with a relentless curiosity to discover nature’s secrets and a Buddhist insistence on knowing “how to solve every problem that’s already been solved.” In the course of an afternoon and evening in his office, he learns that an old terminal illness has returned, and he must decide whether to undergo surgery again or let nature take its course.

You or I might make such a decision for any number of rational, emotional or spiritual reasons, but Feynman’s belief system inhabits a different plane: This is a professor who teaches his students that “If you ask nature the right question, she will give you the right answer,” but on the other hand, “Not knowing is much more interesting than believing in an answer that may be wrong.” Death is the fascinating unknown here; will Feynman pass up the opportunity to observe it firsthand?

I found the whole concept engrossing and profoundly moving, especially since transferring such a drama from a man’s published and private papers to stage is no mean feat. Something else moved me as well: The realization that we live in an age when audiences are sufficiently sophisticated to find stimulation in plays about ideas— as opposed to, say, tap-dancing and frontal nudity. In effect QED (as well as other recent science-oriented plays, like Proof) tells us, “Ideas can be sexy, too.” Since its inception in 1994, the Lantern Theater folks have attempted to corner this market niche. They haven’t always succeeded, but for my money, this time they’ve connected in spades.

To read Jim Rutter's response, click here.

DAN ROTTENBERG

Permit me to dissent from Jim Rutter’s review of QED, currently offered by the Lantern Theater Company. Rutter finds the production “worth seeing for several reasons, chief among them to witness what a talented actor can achieve”— specifically, the remarkable Peter DeLaurier in the role of the late Nobel physicist Richard Feynman. Rutter’s quarrel lies with “Peter Parnell’s one-dimensional script, which fails to capture the magnitude of this remarkable man’s life,” which “reveals little and dramatizes even less.”

Rutter suggests that we’d be better off reading Feynman’s extensive writings, on which Parnell’s play is based. No doubt we would. Perhaps we’d also be better off reading the poems of T.S. Eiiot than attending Cats. But sometimes it takes a creative mind to perceive the dramatic stage possibilities in words on paper. Feynman has been dead for 18 years, and no one saw him as grist for a drama until Parnell come along.

And QED is indeed dramatic, even if the drama takes place entirely within Feynman’s head. The protagonist is a physicist with a relentless curiosity to discover nature’s secrets and a Buddhist insistence on knowing “how to solve every problem that’s already been solved.” In the course of an afternoon and evening in his office, he learns that an old terminal illness has returned, and he must decide whether to undergo surgery again or let nature take its course.

You or I might make such a decision for any number of rational, emotional or spiritual reasons, but Feynman’s belief system inhabits a different plane: This is a professor who teaches his students that “If you ask nature the right question, she will give you the right answer,” but on the other hand, “Not knowing is much more interesting than believing in an answer that may be wrong.” Death is the fascinating unknown here; will Feynman pass up the opportunity to observe it firsthand?

I found the whole concept engrossing and profoundly moving, especially since transferring such a drama from a man’s published and private papers to stage is no mean feat. Something else moved me as well: The realization that we live in an age when audiences are sufficiently sophisticated to find stimulation in plays about ideas— as opposed to, say, tap-dancing and frontal nudity. In effect QED (as well as other recent science-oriented plays, like Proof) tells us, “Ideas can be sexy, too.” Since its inception in 1994, the Lantern Theater folks have attempted to corner this market niche. They haven’t always succeeded, but for my money, this time they’ve connected in spades.

To read Jim Rutter's response, click here.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Dan Rottenberg

Dan Rottenberg