Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

They knew what they had to do

Defying the Nazis in Vichy France

Caroline Moorehead’s recently published Village of Secrets: Defying the Nazis in Vichy France relates the inspiring story of villagers in south-central France who rescued hundreds, and possibly thousands, of Jews and other fugitives from the Nazis during the German occupation of France in World War II. In his recent review of Moorehead’s book, the novelist Louis Begley properly praises the Protestant inhabitants of the Vivarais-Lignon plateau who undertook this courageous venture. (See “The Good Place in Vicious France,” New York Review of Books, Dec. 18.) But Begley implies that their efforts were an exception in a predominantly Catholic and anti-Semitic country.

His thesis may be correct for the most part, but I’m personally aware of at least one French Catholic community that engaged in similar wartime heroics: the area around Le Buet and Vallorcine, two Savoyard villages in the French Alps, where neighbors funneled hundreds of fugitives into neutral Switzerland.

‘Are you Jewish?’

I first learned of this effort in the 1980s, when I was engaged to edit the memoir of one such fugitive, a Belgian Jew and Resistance courier named Alexander Rotenberg (no relation to me), who in the fall of 1942 was guided across the Alps to safety by a seemingly well-organized network of total strangers.

Alex, who was then 21, and a companion named Ruth Hepner had been sent from the French Riviera to the Alps to scout communities along the Swiss border for sympathetic farmers and mountaineers who could help fugitives escape into Switzerland. They were furnished with false identification papers and instructed to pose as amorous students on a vacation.

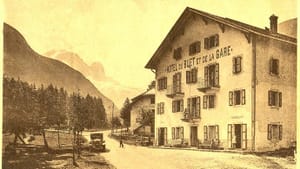

Unfortunately, in their tropical Riviera outfits, Alex and Ruth stood out like sore thumbs in the cool Alpine mountain air. As soon as they had checked in at the Hotel du Buet, the proprietress — one Germaine Chamel — took them to their room, shut the door and asked, in a hushed voice, “Tell me, are you Jewish?”

Alex and Ruth insisted that they were merely vacationing students. But Mme. Chamel seemed unconvinced. She told them that a number of Jews in the vicinity had been arrested while attempting to flee into Switzerland; a group of these Jews would be brought to her hotel that very night for a final meal before being taken away, presumably to concentration camps.

The following morning, Madame Chamel returned to Alex and Ruth’s room and again urged them to take her into their confidence so she could help them escape. But Alex and Ruth stuck to their original story; after all, for all they knew Mme. Chamel could have been a German collaborator.

Snap decision

That afternoon, Mme. Chamel approached the young couple yet again, this time with a warning from the gendarme who had checked their papers the previous day: The papers were suspected as false, Mme. Chamel said, and if the suspicion was confirmed by 5 p.m., Alex and Ruth would be arrested.

At this point, for whatever reason, Alex and Ruth made a snap decision to trust Mme. Chamel. It was a lucky choice. She immediately introduced them to an anti-Nazi German woman, who in turn took them to an Alpine guide — precisely the sort of man they had been sent to find in the first place. He provided them with heavy shoes, socks, and sweaters, and that night he took them by foot across the Alps into Switzerland, where they spent the rest of the war in safety (albeit in an internment camp).

Unanswered question

More than 30 years later, having established himself as an insurance broker in New York, Alex returned to Le Buet in 1976 to track down these Savoyards who had saved his life that day. He found Mme. Chamel still running the inn at Le Buet. (It’s still operated by her family today — click here.) She introduced Alex to a whole network of neighbors who, led by a grizzled country priest name André Payot, had actively aided fugitives from the Nazis. Louis Pache, the Alpinist who had guided Alex and Ruth into Switzerland, was dead, but Alex found Pache’s three sons, who vividly recalled how, that night in 1942, their mother had told them to get down on their knees and pray for Alex and Ruth’s safe arrival in Switzerland.

Alex subsequently returned to Le Buet to throw a banquet for his former benefactors; he had their names inscribed in the list of “righteous gentiles” at Yad Vashem, the Holocaust memorial in Jerusalem; he presented a silver plaque to Mme. Chamel; and he wrote a book about his experience (Emissaries, Citadel Press, 1987). But his saviors were unable to shed much light on the critical question behind their willingness to put their lives on the line for helpless strangers: In a crisis, what makes some people do the right thing while others find excuses to do nothing?

“We all just seemed to know that we had to do what we could to stand up and fight the Germans,” the Abbé Payot told Alex, “even when that meant defying our own [national] leaders.” But of course most people in wartime France and elsewhere did no such thing.

Here’s my explanation: These Savoyard villagers did the right thing because they knew and trusted each other through long association (the Chamels had operated their hotel since the 1890s). And they reinforced their values each week in Payot’s church, so there was never any question among them as to how they would behave in a given situation. They constituted a community in the best sense of the word.

What, When, Where

Village of Secrets: Defying the Nazis in Vichy France. By Caroline Moorehead. Harper, 2014; 384 pages, $27.99. www.amazon.com.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Dan Rottenberg

Dan Rottenberg