Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

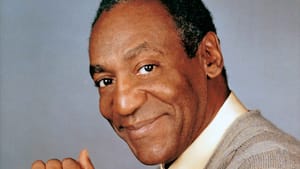

‘Your job is to make Mr. Cosby look good’

The decline of Bill Cosby

More than 50 years ago, while wandering around Greenwich Village, my brother and I ducked into the fabled Bitter End. It was amateur night, when any aspiring entertainer could test his or her material in front of a live audience. Most of the acts were terrible, but one stood out: an unassuming 24-year-old black kid from Philadelphia. Bill Cosby, then unknown, performed a skit about college fraternity initiations; then he did his dialogue between God and Noah, which later became nationally famous.

What impressed everyone at the Bitter End that night was not merely Cosby’s gentle and impish personality but the universality of his humor: His jokes were utterly nonracial, which was rare indeed for a black comic in 1961. Cosby appealed to us not as a black man but as a fellow human being.

Over the next quarter-century, Cosby toppled racial barriers in TV programs like I Spy (the first integrated TV series) and The Cosby Show (the first black family series aimed at a mainstream audience). His subsequent transition from stand-up comic and TV actor to producer, author, and commercial pitchman has generated a personal net worth of $350 million, according to Forbes Magazine. Much of that wealth has been built on Cosby’s shrewd control of his public persona as a warm, wise, charming, and witty exponent of personal responsibility and universal middle-class values — the sort of reputation that money can’t buy.

Ghostwriters

But this is the same warm and witty Bill Cosby whose arrogant TV operation was once exposed in the diary of a contestant on You Bet Your Life, Cosby’s hit show of the early ’90s. “Just before we tape,” the diarist wrote, “the producer tells one contestant, ‘Your job is to make Mr. Cosby look good. Don’t try to make yourself look good, or he’ll chew you up and spit you out.’”

To be sure, Cosby is the author of a dozen or so warm, witty, and wise (albeit short) bestsellers, like Fatherhood and Time Flies. The only trouble with these books is that Cosby didn’t actually write them. Virtually all of his books were written with a collaborator, and anyone who knows the workings of celebrity-collaboration books can safely assume that the collaborator did most (and maybe all) of the writing. The late Ralph Schoenstein — coauthor of Fatherhood and Time Flies — was a genuine humorist with a dozen books of his own to his credit, but he never had a bestseller until he wrote under Cosby’s name.

Sex accusations

And, yes, this is the same Bill Cosby who has been accused of sexual harassment by at least 14 women, most recently a former aspiring actress who surfaced in the Washington Post last week to claim that Cosby “brainwashed me into viewing him as a father figure, and then assaulted me multiple times” in his New York home in 1985, when she was 17. (Click here.)

Cosby has never been criminally charged in any case; he could conceivably be the victim of women projecting their own fantasies upon him in much the same way that he has projected his own fantasies about himself upon the world. But Cosby did settle a civil suit in 2006, in which a former Temple University employee had accused him of drugging, groping, and digitally penetrating her in his Cheltenham home.

Are you astonished that Cosby’s carefully controlled personal narrative doesn’t jibe with the real, fallible human Bill Cosby? Cosby has been dropping hints to that effect throughout his career — as far back as that very first night that I saw him at the Bitter End.

God speaks

At the end of his set, Cosby told the audience, “I guess you expect me to tell a racial joke.” Almost grudgingly, he conveyed a gentle tale about a black minister in Mississippi whose civil rights activity gets him chased out of the state by the Ku Klux Klan. He flees to the safety and comfort of New York City, only to be visited one day by the voice of God, insisting that he return to Mississippi.

“Well, God,” asks the terrified minister, “if I go back to Mississippi, will you go with me?”

“Yes, my son,” God replies. “I will go with you.” Pause. “As far as South Philadelphia.”

In retrospect, it was a prophetic joke. The minister in Cosby’s story lost his essence when he opted for life’s easy road. Something similar happened to Bill Cosby — a man who might have lived up to his avuncular self-image if he hadn’t accumulated quite so much money, power, and influence. Or as Charles Foster Kane put it in Citizen Kane, “If I hadn’t been very rich, I might have been a really great man.”

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Dan Rottenberg

Dan Rottenberg