Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

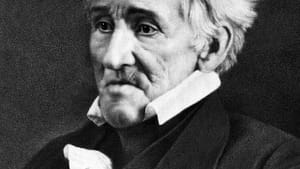

A slave-owner and an Indian-killer

A response to 'A defense of Andrew Jackson'

In a recent column, Dan Rottenberg addressed what he sees as an unfair characterization of Andrew Jackson as, in Gail Collins’s words, a “slave-owner who came to national renown as an Indian-killer.” Unfortunately, Rottenberg doesn’t really engage with either of these issues in his defense of Jackson.

Slave-owner

“He owned slaves,” Rottenberg writes, “although, to judge from his slaves’ tears at his funeral, he was a relatively benevolent master.” This, if intended as a substantive defense, is just embarrassing.

First, there are numerous problems with the evidence itself: Who says they cried? Might that person have an agenda? If one or more of the slaves did cry, how many cried, and how hard? Were the tears, if any, possibly tears of joy or an indication of fear of the future? If they were tears of sorrow at the loss of “a relatively benevolent master,” do such tears indicate overall satisfaction with, or a preference for, lives in bondage? If the slaves in question were, in fact, happy to be the property of another human being, does that make slavery right?

Let’s assume for the moment, though, that some or all of Jackson’s slaves did cry tears of genuine sorrow at his funeral. That evidence of Jackson’s “relatively benevolent” private involvement with slavery ignores his public involvement — his efforts as the president of the United States to silence abolitionist voices, through such efforts as his support of a resolution that forbade anti-slavery petitions in Congress.

Granted, the slavery issue was immensely complicated, from a political point of view, during the 1830s, but clearly Jackson’s sympathies were with the South. Even if his own slaves were sad about his death, there were millions of men, women, and children — 2,487,355, to be precise, according to the 1840 census — who were also enslaved. I’m fairly confident none of them, had they been apprised of Jackson’s death in 1845, would have shed a tear.

Indian-killer

Rottenberg’s defense of Jackson’s genocidal proclivities is equally ill-reasoned. “He fought Indians tenaciously,” he writes, “but at the time, Jackson was a soldier and Indian tribes were technically considered hostile foreign nations.” Yes, Jackson was a commander during the Creek War, after which he overturned a treaty that would have allowed the Creek to keep some land if they stopped dealing with foreign countries. Instead, Jackson, having been promoted to major general, imposed terms that took 22 million acres from the Creeks for Euro-American settlement (and launched what would become his political career).

Fine: The Creeks (Seminoles, Shawnee, and Cherokee, et al.) were “technically considered hostile foreign nations” — but surely anyone with even a passing familiarity with European history of the 1930s and ’40s should be more than a little uncomfortable with a “just following orders” defense, even if, in fact, all he were doing was following orders.

Many critics, at the time and since, however, found that he far exceeded those orders. For instance, during the First Seminole War, he was ordered to prevent Florida from becoming a refuge for runaway slaves — there’s that pesky slavery issue again — but instead invaded territory belonging to Spain, a nation with which the United States was not at war. It’s all good, though — Rottenberg sunnily concludes that the departure of the Spanish “may be the best thing that ever happened to Florida.”

Again, far more troubling than Jackson’s activities as an individual are those he undertook as president. As soon as he got into office in 1829, he proposed and began implementation of the Indian Removal Act, designed to get the Five Civilized Tribes (the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Chocktaw, Muscogee-Creek, and Seminole nations) off their land in the southeast and move them west of the Mississippi.

The most infamous ensuing event was the forced relocation of the Cherokee, which has come to be known as the Trail of Tears. About 16,000 men, women, and children were rounded up by federal troops and sent on a 1,200-mile journey, ill-provisioned and on foot, to Oklahoma; of those 16,000 human beings, about 4,000 died. Other tribes suffered similar losses: The Chocktaw lost 2,500-6,000 of the 17,000 kicked off their land and the Creek 3,500 of 15,000.

Those genocidal numbers are the first thing to come to mind when I hear Jackson called an Indian-killer.

So, is Jacksonian democracy a good thing? Sure.

Is considering Jackson’s treatment, personal and political, of blacks and Native Americans an example of political correctness gone awry, of unfairly “judging a 19th-century figure by 21st-century standards”? No, not at all.

After all, he was a slave-owner and an Indian-killer.

For Tom Purdom's consideration of the related issue of whether presidents should be on U.S. currency at all, click here.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Judy Weightman

Judy Weightman