Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

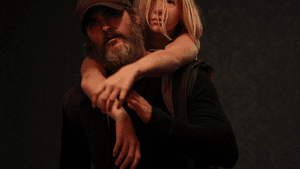

Divine hammer

Lynne Ramsay's 'You Were Never Really Here'

Scottish director Lynne Ramsay works slowly and carefully: four feature films over the past two decades, beginning with Ratcatcher in 1999. Her attention to detail and penchant for the macabre are on display in You Were Never Really Here, which won the Cannes Festival prize for its lead actor, Joaquin Phoenix, and for Ramsay’s own adaptation of Jonathan Ames’s novella of the same name.

Before a word is spoken, the film’s visual presence stuns, beginning with the opening shot of a head encased in a plastic bag, gasping for breath. This claustrophobic atmosphere is maintained by intense closeups, gradually yielding to a succession of hallways, alleys, and train grids, then wider vistas culminating in the film’s climactic scene.

The images rush upon one another in the jump-cutting beloved of modern film, but each shot registers and each one counts. Ramsay respects the craft of film as few contemporary directors do. The camera narrates, and every other element — plot, dialogue, acting — fits within it. The question, though, is what story the narration finally amounts to.

Hammer for hire

Joe (Phoenix) is, literally, a hammer for hire, a jack of all trades who does his wet work with a black ball-peen: quiet, untraceable, and highly effective. He specializes, though, in rescuing young girls being trafficked for sex, an interest that, as flashbacks suggest, goes back to childhood abuse and trauma in Afghanistan.

Joe’s violence, accordingly, is as much directed toward himself as others; the face in the bag is his own, and we see him at various times either fantasizing or contemplating suicide. At the same time, we see him caring, tenderly if equivocally, for an elderly mother (Judith Roberts), in a relationship whose overtones suggest his imprisonment in the past.

The plot that unfolds is melodramatic in the extreme. Joe is hired to track down Nina (Ekaterina Samsonov), the kidnapped daughter of a New York state senator. Her abduction finally leads to the governor through a ring of corruption and murder that catches up Joe’s own mother.

There is a good deal of Martin Scorcese’s Taxi Driver in this tale, but driven to and perhaps beyond the point of sensationalism. Ramsay is uninterested in the mechanics of wickedness in high places; each turn in the plot simply appears. As the bodies pile up under Joe’s hammer — we see him buying a new one (“Made in USA”) early in the film, suggesting he has worn out some predecessors — we are left with the sense of a deranged superhero caught up in a cycle of violence that is simply an end in itself.

Outstanding performance

The film is held together by Phoenix, whose raw intensity defines virtually every scene, conveying unplumbable depths of hurt and rage. With little dialogue, it is Phoenix’s body that speaks. Scarred and welted, heavy-shouldered and pot-bellied, it is simultaneously vulnerable and menacing, with a hoarded violence that can turn in any direction, including on itself.

There is no way to get such a performance except by internalizing one’s character and then projecting it through every fiber and sinew. No other actor working today is capable of such an alchemy. If it is not enough to rescue the film, it does make it hauntingly memorable.

The shock of the film’s last scene belies the weakness of its resolution. One can believe anything about Nina and Joe except a happy ending, even of the most tentative kind. Ramsay’s response, I’m sure, would be that every plot sends itself up in one way or another, so anything is possible. But beautiful composition and a magnificent performance are not ends in themselves. We need a humanity that, even if we cannot fully entertain it, is at least plausible.

What, When, Where

You Were Never Really Here. Written and directed by Lynne Ramsay, based on the book by Jonathan Ames. Philadelphia-area showtimes.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Robert Zaller

Robert Zaller