Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

The Philadelphia Orchestra's season concludes with a first and a last

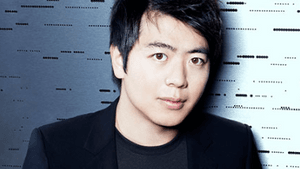

Yannick Nézet-Séguin concludes the Philadelphia Orchestra's 2015-16 season

Yannick Nézet-Séguin concluded the Philadelphia Orchestra’s 2015-16 season, as usual, a month ahead of its neighbor, the New York Philharmonic, whose concerts continue into June. This final concert included the first work Sergei Rachmaninoff gave an opus number, the Piano Concerto No. 1 in F Sharp Minor of 1891, and Gustav Mahler’s 10th Symphony, left incomplete at his death in 1911. The saga of both these works only begins with their original dates of composition.

Rachmaninoff revised his concerto extensively in 1917, and today, we hear it in this latter form. The Mahler 10th was completed in short score, but Mahler managed to fully orchestrate only the first of its five movements. The composer’s widow, Alma, withheld the score from view and performance for decades. It finally became public with the great Mahler revival of the 1960s, and conductors hastened to perform and record the lengthy first movement Adagio, whose broad architecture and self-contained drama made it a viable work on its own.

The Adagio is still frequently performed by itself on concert programs, but musicologists took a keen interest in the unscored movements of the symphony, which not only carried the whole work to the conclusion of which the Adagio itself was part, but represented Mahler’s final thoughts as a composer. Could it be made, if not what Mahler would have given us to hear, at least playable? The British musicologist Deryck Cooke orchestrated the final four movements, and presented the result as what he called a “performing version” of the symphony’s draft. Cooke did a credible job, and though others have tried their hands at orchestrating the 10th, his remains the preferred version.

Mahler’s greatest achievements

Structurally, the 10th consists of two stupendous slow movements that bookend three shorter fast ones, two scherzos and an allegretto. The slow movements are, by turns, philosophic, elegiac, and tragic in character, and have been read as Mahler’s leavetaking. The inner movements seem to evoke and reflect on the activity of life. His Ninth Symphony is similarly built on a five-movement arch form, and though Mahler is never less than interesting, the middle movements of both the Ninth and the 10th make for a longish stretch of busyness; less, perhaps, would have been more.

However, the first and final movements of the 10th are among the composer’s greatest achievements, the latter recapitulating material from the previous movements, including the huge and still staggeringly dissonant climax of the Adagio (a tactic Shostakovich would use in his five-movement Eighth Symphony, though it is unlikely he could have been aware of the Mahlerian precedent). The music fades out, rather like that of Mahler’s Ninth or his Das Lied von der Erde, with a deep resignation that should not, I think, be taken as acceptance: Mahler would rage to the end against the dying of the light.

Certainly Mahler was not ready for a final valedictory with the 10th, where his harmonic language and rhythmic exploration suggest an artist experimenting stylistically. How, one wonders, would he have responded to his younger contemporary Schoenberg had he lived another decade or two? The opening measures of the 10th are still deeply Wagnerian, but by the time the Adagio has run its course, we are in a world not far from musical Expressionism and even anticipating serialism.

Ragged and vulgar

Nézet-Séguin and the Orchestra sounded a bit ragged in the Adagio, and the strings were a beat late coming in on the movement’s climax. Things went better thereafter, with the tricky rhythms and off-beat entrances of the middle movements well handled, while the Finale was deeply expressive. If Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony is your classic wind-up to a concert season, the Mahler 10th is its polar opposite, fading away into the stillest of silences. On the other hand, it may better fit the mood of 2016.

Lang Lang was the soloist in the Rachmaninoff First Concerto, and at this point, what is there to say about him? He’s a technician of staggering gifts who can get anything he wants out of a piano except music. The notes as written are for him a pretext for virtuosity, or simple exhibitionism. He can vulgarize Mozart, Chopin, and Rachmaninoff with equal aplomb, and of course his tempos — arbitrarily speeded up or slowed down — play havoc with an accompaniment: he had Nézet-Séguin dragging the Orchestra’s strings through syrup one minute, and playing frenetic catch-up the next. Of course he got his usual standing ovation at the end, although I noticed here and there people were sitting on their hands as well as their seats. I don’t know whether Lang will ever mature as a musician or simply remain the Liberace of classical music, but the odds aren’t getting better.

Meanwhile, New York beckons Nézet-Séguin, with a vacancy at the Met Orchestra. The summer should be interesting.

What, When, Where

The Philadelphia Orchestra: Sergei Rachmaninoff, Piano Concerto No. 1 in F Sharp Minor, Op. 1; Gustav Mahler, Symphony No. 10. Yannick Nézet-Séguin, conductor. Lang Lang, soloist. May 12-14, 2016. at the Kimmel Center's Verizon Hall, Broad and Spruce Streets. (215) 893-1999 or www.philorch.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Robert Zaller

Robert Zaller