Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

He saw with his eyes and his heart

"Van Gogh Up Close' at the Art Museum (2nd review)

The Philadelphia Museum of Art's last comprehensive exhibition of Van Gogh's work included many of his famous and coveted portraits"“ of himself, the postman Joseph Roulin, Madame Berceuse and others, along with other works, including the stunning Starry Night. The impact was overwhelming: People were weeping openly in the galleries because of the extraordinary humanness and vulnerability of both the artist and his subjects.

The Art Museum's new exhibit, "Van Gogh Up Close," may be as well attended and appreciated, but the impact is likely to be very different. The artist's personal sensibility is there, but the paintings"“ close-ups of flowers, taut condensed landscapes, and broader perspectival renderings, with styles that vary from Impressionist to Pointillist to fluid and fragmented"“ invite you to peer into the art itself: the ways in which van Gogh used light, color, brush strokes, texture, perspective, placement, and other features to convey moods, movement, and states of mind.

This exhibit reveals a brilliant artist who used every means at his disposal to stretch the limits of art in ways that anticipated future developments. It's understandable that this suffering individual, mostly unrecognized and living on the edge of poverty, could pour his humanity into his paintings and evoke profound emotion.

It's almost incomprehensible, however, how with the limited time and resources at his disposal he could have summoned the mental energy and quickness of mind to grasp and use so many elements of art so eloquently in his work.

How we see

Even at the edge of madness (or whatever malaise led to his hospitalization"“ some think it epilepsy, others a hearing disorder, and still others alcoholism), Van Gogh's paintings reflect extraordinary intelligence and intuition. Most paintings in this exhibition date from the last four years of his life (1887-1890), and you can see the shifts in his mood and consciousness during this time, from joy to sorrow and from order to disarray and fragmentation. Yet all the work is infused with aesthetic balance and significance.

Van Gogh understood more than any other artist, and from new and experimental vantage points, how we see. Since the Renaissance, artists faithfully reproduced the world of objects, either with great realism or from the point of view of myth, symbolism and story. The pioneering Impressionists, like Manet, Monet and Pissaro, shifted the emphasis to what was seen by the eye itself: light and color, with form and content emerging from the light itself.

Cézanne, although an Impressionist, also painted with an abstraction of shapes and colors that anticipated Cubism. Van Gogh took these cues and transcended them to a new understanding.

Anticipating neuroscience

Van Gogh recognized that we see (and artists paint) with everything that constitutes our experience and our being in the world. This understanding emerged only later in the intellectual trends of phenomenology, existentialism and, most recently, neuroscience.

The philosophers Husserl, Heidegger and Merleau-Ponty have held in different ways that what we see (consciousness) is a holistic function of our being, our actions and our relationship to the world. The neuroscientist Antonio Damasio, elaborating on views expressed much earlier by Freud, has suggested (in his book The Feeling of What Happens) that our perceptions and cognitions are shaped by our desires, emotions, and behaviors.

One painting, two realities

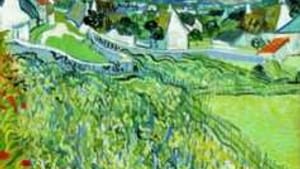

This notion is amply reflected in Van Gogh's work. For example, in his painting Vineyards at Auvers, the vineyards at the lower left of the canvas and the village leaning toward the upper right are separated diagonally, and the artist used entirely different brush strokes to convey the lushness of the vines versus the geometrical clustering of the homes in the village. He saw them in two different ways, suggesting a kind of splitting into two different realities.

This presentation might have reflected the divisions within van Gogh's troubled mind, but it also shows how his brush strokes influenced what he saw and vice-versa. The diagonal division of the canvas further reflects his interest in Japanese art, and this exhibit includes a section of such works from Van Gogh's time, with their displacements of objects and scenes. Van Gogh used a wide swath of the artistic trends and influences then making the rounds of salons and studios.

Van Gogh's paintings of flowers— sunflowers and irises were among his favorites and most loved by viewers— are displayed prominently in the exhibit's first galleries. They're painted with a fullness of feeling, as if the artist's soul merged with those of the flowers themselves. His use of rapid brush strokes, each of which captures something essential, mirrors both the impressionist quickness of response and the Zen-like single-stroke paintings from Japan, which he may have known about through the works of the immortal Hokusai and others.

Dancing wheat sheaves

But as you move through the gallery, you encounter paintings of wheat, our humble, simple "daily bread." Here van Gogh takes steps into Modernism.

In Ear of Wheat, he invokes a recurrent design in the manner that Matisse later adopted as his trademark. In Field with Wheat Stack, we see the brush strokes as much as the wheat, a technique that approaches modern abstraction.

In Sheaves of Wheat, his brush strokes create a sense of movement, and the sheaves seem almost like dancers. The whole painting is pale, with a minimal palette of colors, as if seen in a mist. Here we discern a touch of Picasso's drawings and Les Demoiselles d'Avignon.

Gloomy prophecy

Van Gogh's stark Rain (1887) may be one of the most interesting paintings in all of art, almost prophetic in its gloom. The painting has a large area of nothing, and a wall that slices across the canvas demarcates an existential abyss. The falling rain veils the whole canvas. The sadness, greyness, and lines of rain foretell the 20th-Century loss of innocence and perhaps also reflect Van Gogh's state of mind (he painted it from the window of his room in the asylum in St. Remy).

The exhibit's last gallery displays a section of photographs from the late 19th Century. The commentary notes that Van Gogh didn't like photography, and the paintings in this exhibit suggest why he didn't appreciate that new art form.

Van Gogh saw the world not through the lens of his eyes alone, but through his heart, his emotions, his love of brush and thick gouaches of paint, the multitude of "here-and-now" acts of putting paint to canvas, and a profound vision of the miracle of life.♦

To read another review by Andrew Mangravite, click here.

To read another review by Robert Zaller, click here.

To read a response, click here.

To read a response by Victoria Skelly, click here.

The Art Museum's new exhibit, "Van Gogh Up Close," may be as well attended and appreciated, but the impact is likely to be very different. The artist's personal sensibility is there, but the paintings"“ close-ups of flowers, taut condensed landscapes, and broader perspectival renderings, with styles that vary from Impressionist to Pointillist to fluid and fragmented"“ invite you to peer into the art itself: the ways in which van Gogh used light, color, brush strokes, texture, perspective, placement, and other features to convey moods, movement, and states of mind.

This exhibit reveals a brilliant artist who used every means at his disposal to stretch the limits of art in ways that anticipated future developments. It's understandable that this suffering individual, mostly unrecognized and living on the edge of poverty, could pour his humanity into his paintings and evoke profound emotion.

It's almost incomprehensible, however, how with the limited time and resources at his disposal he could have summoned the mental energy and quickness of mind to grasp and use so many elements of art so eloquently in his work.

How we see

Even at the edge of madness (or whatever malaise led to his hospitalization"“ some think it epilepsy, others a hearing disorder, and still others alcoholism), Van Gogh's paintings reflect extraordinary intelligence and intuition. Most paintings in this exhibition date from the last four years of his life (1887-1890), and you can see the shifts in his mood and consciousness during this time, from joy to sorrow and from order to disarray and fragmentation. Yet all the work is infused with aesthetic balance and significance.

Van Gogh understood more than any other artist, and from new and experimental vantage points, how we see. Since the Renaissance, artists faithfully reproduced the world of objects, either with great realism or from the point of view of myth, symbolism and story. The pioneering Impressionists, like Manet, Monet and Pissaro, shifted the emphasis to what was seen by the eye itself: light and color, with form and content emerging from the light itself.

Cézanne, although an Impressionist, also painted with an abstraction of shapes and colors that anticipated Cubism. Van Gogh took these cues and transcended them to a new understanding.

Anticipating neuroscience

Van Gogh recognized that we see (and artists paint) with everything that constitutes our experience and our being in the world. This understanding emerged only later in the intellectual trends of phenomenology, existentialism and, most recently, neuroscience.

The philosophers Husserl, Heidegger and Merleau-Ponty have held in different ways that what we see (consciousness) is a holistic function of our being, our actions and our relationship to the world. The neuroscientist Antonio Damasio, elaborating on views expressed much earlier by Freud, has suggested (in his book The Feeling of What Happens) that our perceptions and cognitions are shaped by our desires, emotions, and behaviors.

One painting, two realities

This notion is amply reflected in Van Gogh's work. For example, in his painting Vineyards at Auvers, the vineyards at the lower left of the canvas and the village leaning toward the upper right are separated diagonally, and the artist used entirely different brush strokes to convey the lushness of the vines versus the geometrical clustering of the homes in the village. He saw them in two different ways, suggesting a kind of splitting into two different realities.

This presentation might have reflected the divisions within van Gogh's troubled mind, but it also shows how his brush strokes influenced what he saw and vice-versa. The diagonal division of the canvas further reflects his interest in Japanese art, and this exhibit includes a section of such works from Van Gogh's time, with their displacements of objects and scenes. Van Gogh used a wide swath of the artistic trends and influences then making the rounds of salons and studios.

Van Gogh's paintings of flowers— sunflowers and irises were among his favorites and most loved by viewers— are displayed prominently in the exhibit's first galleries. They're painted with a fullness of feeling, as if the artist's soul merged with those of the flowers themselves. His use of rapid brush strokes, each of which captures something essential, mirrors both the impressionist quickness of response and the Zen-like single-stroke paintings from Japan, which he may have known about through the works of the immortal Hokusai and others.

Dancing wheat sheaves

But as you move through the gallery, you encounter paintings of wheat, our humble, simple "daily bread." Here van Gogh takes steps into Modernism.

In Ear of Wheat, he invokes a recurrent design in the manner that Matisse later adopted as his trademark. In Field with Wheat Stack, we see the brush strokes as much as the wheat, a technique that approaches modern abstraction.

In Sheaves of Wheat, his brush strokes create a sense of movement, and the sheaves seem almost like dancers. The whole painting is pale, with a minimal palette of colors, as if seen in a mist. Here we discern a touch of Picasso's drawings and Les Demoiselles d'Avignon.

Gloomy prophecy

Van Gogh's stark Rain (1887) may be one of the most interesting paintings in all of art, almost prophetic in its gloom. The painting has a large area of nothing, and a wall that slices across the canvas demarcates an existential abyss. The falling rain veils the whole canvas. The sadness, greyness, and lines of rain foretell the 20th-Century loss of innocence and perhaps also reflect Van Gogh's state of mind (he painted it from the window of his room in the asylum in St. Remy).

The exhibit's last gallery displays a section of photographs from the late 19th Century. The commentary notes that Van Gogh didn't like photography, and the paintings in this exhibit suggest why he didn't appreciate that new art form.

Van Gogh saw the world not through the lens of his eyes alone, but through his heart, his emotions, his love of brush and thick gouaches of paint, the multitude of "here-and-now" acts of putting paint to canvas, and a profound vision of the miracle of life.♦

To read another review by Andrew Mangravite, click here.

To read another review by Robert Zaller, click here.

To read a response, click here.

To read a response by Victoria Skelly, click here.

What, When, Where

“Van Gogh Up Close. †Through May 6, 2012 at Philadelphia Museum of Art, Ben. Franklin Parkway and 26th St. (215) 763-8100 or www.philamuseum.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Victor L. Schermer

Victor L. Schermer